Miscellaneous Items

The Story of the 101st Airborne Division: RENDEZVOUS WITH DESTINY

I want to thank Bill Tingen for this most interesting booklet he sent me, which tells the story of the 101st Airborne Division.

The booklet, we think, has been printed in 1945.

Of course it is not as new, after all it has been through, we can say it is in a very good shape. It has survived the years in a wonderful way, and if it could talk, we should be surprised it is still in that condition.

Only the first and the last pages are a bit difficult to read, but it is such an important and historical document, that we have considered to publish the entire booklet anyway...

"101st Airborne Division" is a small booklet covering the history of the 101st Airborne Division. This booklet is one of the series of G.I. Stories published by the Stars & Stripes in Paris in 1944-1945.

This book is dedicated to the Airborne soldiers who have made the history recorded in its pages. The success of the 101st Airborne Division is not the success of a few outstanding units or leaders. The toll of battle has changed the roster too often to suggest that any particular combination is necessary. Success has been won by the anonymous thousands of officers and men who have passed through the Division since D-Day in Normandy, all imbued with a common spirit of resolution and zest for battle. These men knew but one formula for victory, the will to close with the enemy and destroy him. It is a responsibility to belong to the 101st Airborne Division with its record of achievement. The past matters only as a promise of future accomplishment. We who today wear the Eagle on our shoulders must assure the Division a future worthy of the men of Normandy, Holland, and Bastogne.

Maxwell D. Taylor Major General, Commanding

THE STORY OF THE 101st AIRBORNE DIVISION

"You have a rendezvous with destiny!" with this, Maj. Gen. William C. Lee, the original commander, concluded his activation speech to the 101st Airborne Division. Screaming Eagles have found meaning and expression in these words. They kept that rendezvous with destiny. They kept it in Normandy by initiating the Allied assault on Hitler's Fortress Europe, June 6, 1944; by storming and capturing Carentan -- initial proof of the division's strength in coordinated ground action. They kept it in Holland by liberating the first Dutch city, Eindhoven, and blazing a path of liberation 20 miles northward in a campaign that kept them fighting 73 days without relief. They kept it at Bastogne where against overwhelming odds they held tenaciously to doom von Rundstedt's December counter-offensive to failure.

Success of the division has been the result of a happy combination of brave men commanded by bold leaders. Mutual confidence of the 101st is exemplified by the remark of an Eagle soldier during the siege of Bastogne: "They've got us surrounded - the poor bastards!" A British Corps Commander near the end of the Holland campaign told Screaming Eagle soldiers: "I have commanded four Corps during my army career, but the 101st Airborne Division is the fightingest outfit I have ever had under my command." Maj. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe (then Brig. Gen.) voiced the opinion of division officers for their men when he said at Bastogne: "With the type of soldier I had under my command, possessing such fighting spirit, all that I had to do was to make a few basic decisions -- my men did the rest." His words pay tribute to the gallant fighting Eagle Division men, who kept their "rendezvous with destiny" in Normandy, Holland and Belgium.

NORMANDY: FIRST RENDEZVOUS WITH DESTINY JUNE 6, 1944:

the echoing rifle fire of a 101st A/B Div. "baggy pants" paratrooper heralded the greatest military operation of its kind. The invasion of Europe for which an anxious world waited had begun -- born in hedgerow-lined fields, in apple orchards and in the country lanes of Normandy where paratroopers and glider fighters of Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor's Eagle Division had dropped behind German troops manning beach defenses. As daylight mellowed into dusk June 5, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower circulated among 101st troops at England's departure fields to wish them Godspeed, good luck. Cocky fighters, armed to the hilt and assigned the mission of striking the first blow at Hitler's Fortress Europe, wise-cracked as they boarded C-47s. Less than four hours later in Normandy, these Airborne soldiers wrote the first pages of their glorious story with blood and courage.

They penned the lines of a combat diary with a phrase in French and a hand grenade at Pouppeville, with German dead stacked in roadside ditches on the march to St. Come du Mont, with a blinding bayonet dash across the swampy approaches to Carentan. From 0015 in the darkness of June 6, 1944, when Capt. Frank L. Lillyman, Skaneateles, N.Y., leader of the Pathfinder group, became the first Allied soldier to touch French soil, and for 33 successive days 101st A/B carried the attack to the enemy. This was the beginning of the Airborne trail leading through Carentan in Normandy, to Eindhoven in Holland and into Bastogne. Belgium. Gen. Taylor's sky-fighters had been assigned three missions: secure causeways leading from Utah Beach for assault troops to storm ashore from landing barges at dawn; destroy bridges across roads leading into the key road and rail communication center Carentan; protect the south flank of VII Corps.

Fighting its way through hedge-lined fields, the division took every objective. When the "Battle of the Beaches" was won, many 101st units were awarded the Presidential Citation. Congratulating the division on its work. Lt Gen. Omar N. Bradley told Eagle soldiers: "You have destroyed the myth of German invincibility."

FLAK and fog -- nemesis of cloud-hopping troops. German ack-ack and the weather joined forces to disperse the sky fleet of troop carrier planes ferrying paratroopers over the Nazi-held coastline. Methodical assembly by units was out of the question. Commanders gathered roving bands of well-briefed, battle-hungry Airborne soldiers, regardless of unit, then marched on division objectives. An odd assortment of men was culled from thorn-thick hedges and ditches along roads to storm Pouppeville. Division Commander, Chief of Staff, clerks, MPs, artillerymen, signalmen, a sprinkling of infantry parachutists -- all combined to form a task force against this village that blocked the entrance of a causeway leading from Utah Beach. So abundant were staff officers that Gen. Taylor remarked, "Never were so few led by so many." It was near Pouppeville in early morning darkness that a passing German patrol caught Maj. Larry Legere, Fitchburg, Mass., and thinking him a French native, asked him what he was doing out so late. "I come from visiting my cousin," the major replied in French while he pulled the pin on a grenade and let fly. Pouppeville fell to this small band. Similar displays of adaptability and initiative by other groups nullified enemy opposition at similar key points, and causeways were secured for beach assault troops. Early in the day, the 4th Inf. Div. marched up causeways without opposition. The first obstacle to the invasion had been overcome.

At dawn of the second day, the 506th Parachute Inf. Regt., commanded by Col. Robert F. Sink, Lexington, N.C., advanced southward. Germans stubbornly defended previously fortified Vierville. The town was taken after severe fighting, and the enemy grudgingly fell back to St. Come du Mont. Angoville au Plain fell to the division by noon, and skyfighters smashed through hedges and over roads to the outskirts of St. Come du Mont. Resisting savagely, Germans blunted the thrust. The 2nd and 3rd Bns., 501st Parachute Inf.; 1st Bn., 401st Glider and a battery of the 81st AA A/T Bn. moved in to form a second striking force. The Eagle was ready. Ahead lay St. Come du Mont, defended by well dug-in German parachutists.

Here, 101st A/B soldiers were committed in the first large-scale attack launched by the division in the invasion campaign.

From hedgerow to hedgerow, through field after field, onto the road into town, fierce fighting raged as Eagle troopers swept into the streets of St. Come du Mont. Here the 101st Airborne first met the German 6th Parachute Regt., later to be encountered again in the Holland campaign. Twice this crack Nazi unit was to develop a healthy respect for the fighting skill of the "Yankees with the Big Pockets." By 2000 June 7, all organized resistance ceased at St. Come du Mont. Carentan loomed next on the list of vital Allied objectives. Its seizure would provide the link necessary to coordinate the assault forces on Utah and Omaha Beaches. If Germans retained the town, Allied power would be divided during the campaign's most crucial phase. Carentan had to be taken. The Screaming Eagles were assigned the job. But the path leading to it wasn't easy.

Later described as "Purple Heart Lane," the route covered canals, swamp lands and the Douve River, all guarded by Germans. The 327th Glider Inf., commanded by Col. Joseph Harper, College Park, Ga., pushed off to cross the Douve at 0100, June 9. Corps engineers brought up assault boats by concealed routes. Under cover of heavy artillery, the regiment crossed the river, seized the small village of Brevands, secured a supply route to support the attack on Carentan from the east. The 326th A/B Engr. Bn., laying aside weapons of destruction for tools of construction, set up a temporary footbridge across the river on 502nd Parachute Inf.'s front north of Carentan. One battalion attempted to cross by infiltration but was discovered. The crossing temporarily was abandoned. Later, 3rd Bn., commanded by Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole, San Antonio, Tex., followed by 1st Bn. led by Lt. Col. Patrick F. Cassidy, Seattle, succeeded in crossing the four consecutive bridges which span Carentan waterways, established a precarious bridgehead north of the city.

Pinned down, Col. Cole's paratroopers flattened into the marshy swamp for cover. After unceasing enemy fire prevented any move for more than an hour. Col. Cole weighed two plans -- a withdrawal or a bayonet attack. He ordered: "Strip for bayonet attack. Let's get out of this damn swamp!" Word was whispered from man to man in the marshy bed -- "The Old Man wants it done with steel." There, on the last approach to Carentan occurred the first bayonet attack of World War II. With bull-like charges through the soggy marsh, paratroopers rushed forward to close with the Kraut defenders. Picking up a fallen man's rifle and bayonet, Col. Cole led the battalion over the bullet-swept ground.

Locked in hand-to-hand fighting, Eagle paratroopers forced back the Germans, subdued the last defenders. For his heroic action, Col. Cole won the Congressional Medal of Honor, posthumously awarded. He was killed the second day of the Holland invasion. It was with this spirit that the division, attacking Carentan from three directions, achieved its objectives. Resistance ceased within the city June 11. A defensive position was immediately organized. Later near Cherbourg, Gen. Taylor stood high atop a captured pillbox and told his battle-hardened veterans, "You hit the ground running toward the enemy. You have proved the German soldier is no superman. You have beaten him on his own ground, and you can beat him on any ground." Field Marshal (then Gen.) Sir Bernard Law Montgomery pinned the British Distinguished Service Order on Gen. Taylor's jacket. The Eagle Division was ordered to its base in England, closing the first chapter in its combat record.

HOLLAND: SECOND D-DAY FOR SCREAMING EAGLES

Where next? This was the question in the mind of every Eagle trooper. By August, 1944, tremendous Allied advances across France and the fluid state of German defenses indicated the likelihood of another Airborne mission.

Twice the division was alerted and moved to departure airdromes to await the battle signal. Twice the division trudged to marshalling fields only to return to base camps. Swift-moving armor eliminated the necessity for both operations. But the third operation wasn't a dry run. Its second combat mission -- Holland! As part of the newly-formed First Allied A/B Army, Eagle soldiers were sent skyward toward German defenses in the land of wooden shoes and windmills. Again it was a sky dash over the English Channel, over flak towers, and down behind German lines. The mission was to secure bridges and the main highway winding through the heart of Holland from Eindhoven to Arnhem to facilitate the advance of Gen. Sir Miles C. Dempsey's Second British Army over the flooded dike-controlled land.

Sept. 17 was the date for the 101st's second Airborne D-Day. The greatest Airborne fleet ever massed for an operation roared from U.K., spanned Channel waters. While the first planes spewed forth parachutists and gliders crash-landed on lowlands, planes and gliders transporting the division still were taking off from Britain air fields. Flak met the invaders enroute, but the huge armada droned steadily on. Troop Carrier formations held firm despite fire. Pilots of burning planes struggled with controls as they flew to designated Drop Zones, disgorged their valuable cargoes of fighting men, then plummeted earthward. Pilot heroism was commonplace, proved inspirational to Eagle sky fighters dropping well behind enemy lines. Surprise was complete. There was little initial opposition from the Germans. Eagle veterans assembled quickly, then marched on their objectives.

Division missions called for the capture of Eindhoven and the seizure of bridges over canals and rivers at Vechel, St. Odenrode and Zon. To attain these objectives the division had to seize and hold a portion of the main highway extending over a 25 mile area. Commanders realized units would be strung out on both sides of the main arterial highway from Vechel to Eindhoven, that security in depth would be sacrificed. Dropping near Vechel, the 501st Parachute Inf. Regt., commanded by Col. Howard R. Johnson, Washington, D.C., later killed in the campaign, pressed forward. Two hours later, Vechel was taken and bridges over the Willems Vaart Canal and the Aa River seized intact. A sharp skirmish marked the speedy liberation of St. Odenrode by the 502nd Parachute Inf. under Col. John H. Michaelis, Lancaster, Pa. Co. H moved to take the highway bridge leading from Best. This small force was successful in its mission but driven back when Germans counter-attacked. The fight for Best raged three days. At stake was a key communications route through which Germans could pour reinforcements.

The enemy was deployed in strength at the Best bridge. The 502nd attacked again the second day to retrieve the bridge but was thrown back. The bridge finally fell at 1800 the third day after one of the most bitter battles of the Netherlands campaign. The Airborne attack, supported by British armor, resulted in the destruction of fifteen 88s and the capture of 1056 Germans. More than 300 enemy dead littered the battlefield.

After landing, Col. Sink's 506th troopers moved toward Zon on the road to Eindhoven. Approaching Eagle soldiers saw Germans blow the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal. Several men swam the Canal in the face of heavy German fire, established a bridgehead on the south bank. This action enabled the remainder of the regiment to cross. Troopers whipped back the Germans as they drove towards Eindhoven five miles to the south. A flanking movement sealed the city's fate.

The first major Dutch city to be liberated, Eindhoven, was in Airborne hands at 1300, Sept. 18. On Sept. 23, Germans severed the main highway between Vechel and Uden. Simultaneously, they made a strong but unsuccessful bid to recapture Vechel. With the highway cut, long caravans of trucks were halted along the narrow road leading from Eindhoven to Arnhem. All available division elements were rushed to the vicinity of Vechel where they were formed into a task force under Gen. McAuliffe. Enemy penetrations were deep. German tanks and infantry moved within 500 yards of the vital bridges. Vicious fighting followed, but the Eagle defense held firm. The enemy was forced to withdraw toward Erp, and the highway was reopened. Next day, a fresh German thrust cut the supply line between Vechel and St. Odenrode. Eagle soldiers combined with British tanks to smash German defenses and again reopen the road. Thereafter the thunderous roar of armor and supply trucks rolling up the highway continued uninterrupted.

Meanwhile, Gen. Taylor shuttled troops up and down both sides of the British Second Army's supply route to repulse German forces determined to sever Gen. Dempsey's lifeline. Airborne troops, glidermen and paratroopers plugged gaps in the line with courage and M-1 rifles. During the campaign in the canal-divided lowlands, hard-hitting Eagle paratroopers and glidermen again met a reorganized Normandy foe, the German 6th Parachute Regt. This crack German unit fared no better than before, sustaining heavy casualties which forced its early removal from the 101st sector. Following this behind-the-enemy-lines "Airborne phase," the 101st moved to an area which soon became known to troops as the "Island." This strip of land was located between the Nederijn and Waal Rivers with Arnhem to the north, Nijmegen to the south.

Arrival of the Screaming Eagle on the Island marked the beginning of the end for Germany's 383rd Volksgrenadier Div. Taking over a quiet sector of the Island, the 101st prepared defensive positions. Within 24 hours Germans struck from the west, slamming their 957th Regt. hard against the Airborne wall. Told it was opposing a handful of isolated Allied parachutists, hungry and without adequate weapons, the Nazi regiment attacked, confidently and swiftly. The assault was absorbed by the depth of the 101st defense. The enemy was stunned at the savage reception accorded him by the "handful of Allied parachutists, hungry and without adequate weapons." Doggedly, the Germans drove -- into destruction. Soon, the 957th Regt. ceased to exist as a fighting tactical unit. But the savage warfare wasn't over. Germans reorganized battered elements and the 958th Regt. arrived the next day to join its faltering fellow regiment.

German artillery and armor supported a fresh attack. By nightfall, the Eagle battalion occupying Opheusden, focal point of the German effort for three days of fanatical fighting, withdrew to a defensive line east of the town. Opheusden changed hands several times. Either attacking or withdrawing, skillful Eagle sky-fighters inflicted tremendous losses on the 363rd Div., now completely assembled with the 959th Inf. Regt., 363rd Arty. Regt. and its engineer and fusilier battalions in the fold. Airborne soldiers eventually captured the town, blasted retreating and thoroughly beaten Germans completely out of the Airborne sector. Order of Battle records of enemy killed, wounded and captured provide mute testimony to the destruction of the German division. In its reorganized Volksgrenadier status, the once-proud 363rd Inf. Div. lasted exactly 10 days in the claws of the Screaming Eagles.

From then on, activity in Holland was limited to patrols. Highlighting the action was the work of an intelligence section patrol of the 501st Parachute Inf., led by Capt. Hugo S. Sims, Orangeburg. N.C., Regimental S-2. The patrol crossed the Rhine in a rubber boat at night, and following a number of narrow escapes, reached an observation point on the Arnhem-Utrecht highway, eight miles behind enemy lines. After relaying information back to the division by radio, the patrol captured a number of German prisoners who gave additional data on units, emplacements and movement in the area. Moving out next day, the six-man team nabbed a German truckload of SS troops, including a battalion commander. When the truck bogged down, patrol and PWs, now numbering 31, walked to the river, then crossed over to the American-held bank. Early in November, the division was relieved in Holland and once again returned to a base camp, this time in France.

Screaming Eagles paused for a breather. But it was brief because Eagle troops are not accustomed to resting. Since their activation they have been continually training, maneuvering -- and now fighting.

The 101st A/B Div. was activated Aug. 16, 1942, at Camp Claiborne, La. The 82nd Inf. Div. had been split to form the nucleus for the Army's first two Airborne divisions, the 101st and 82nd. The division trained at Fort Bragg, N.C., participated in Tennessee maneuvers. Overseas movement began Sept. 5, 1943. After arrival in England, Eagle troops continued ground and Airborne training in preparation for its combat missions. Maj. Gen. William Carey Lee, "Father of Airborne Troops," was the first Commanding General of the Screaming Eagles. After guiding the division through the difficult training period, a heart ailment a few months prior to the Normandy D-Day prevented him from realizing his ambition to lead the unit into combat. Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, Chief of Staff, then Artillery Commander of the 82nd A/B Div. with which he fought the Mediterranean campaign in 1943, succeeded Gen. Lee. Brig. Gen. Don F. Pratt was Asst. Division Commander until June 6, 1944, when he was killed while leading the glider echelon into Normandy. Brig. Gen. Gerald J. Higgins, current Asst. Division Commander, at 34, is the youngest ground force general in the Army. Gen. Higgins, who entered West Point from the ranks, has been the Asst. Chief of Staff G-3 and Chief of Staff in the division. Col. William N. Gillmore, Ft. Knox, Ky., succeeded Gen. McAuliffe as Division Artillery commander when the latter took over the 103rd Inf. Div

BASTOGNE: "THE HOLE IN THE DOUGHNUT"

Less than two weeks after fighting in Holland, the 101st was alerted for another mission. At 2400, Dec. 17, unit commanders were told that Germans had broken through Allied lines, were rolling westward across Luxembourg and Belgium. The situation was tense. Many American units had been overrun, others were staggering under the unexpected power of the Wehrmacht blow, The 101st was ordered to move within 12 hours. Clerks, draftsmen and typists hurriedly were awakened. In the dim early morning hours, division, regiment and battalion headquarters personnel raced to ready maps and vital information needed by the first groups before departure.

Gen. Taylor was in Washington on urgent War Department business. Gen. McAuliffe was in command. Fighting men awoke at dawn. In some cases it was "Be ready to leave in four hours!" Others had more time. It was incredible yet true. The well-deserved rest of the 101st was short. Men were needed. All fighting equipment had been turned in, so Division supply room doors now swung open: "Take what you need and be sure you have enough. No forms to sign -- no red tape -- help yourself!" Every man quickly found equipment to transform him from a "resting" soldier back to a veteran ready for combat. German objectives were Liege, Namur, across the Meuse to Antwerp. The plan which sent speeding Panzer columns westward along Belgium's highways called for capture of Bastogne, vital hub of a communication network of seven highways, three railroads. Seizure of Bastogne was imperative to insure development of the German attack. Without the city, Germans could hardly hope to succeed. The 101st rolled to Bastogne in huge carrier trucks. Re-routing sometimes was necessary, but by 2100 a considerable number of men already had arrived at temporary Division Headquarters near the town. As they made their "jump" from the carrier trucks, an Airborne man told a driver: "Wait outside. We'll finish this thing off in a hurry and be right back." With that spirit, Screaming Eagles entered Bastogne at dawn the following morning.

Moving into the city, Airborne troopers met isolated groups of soldiers, passed long vehicular columns, all retreating westward from the breakthrough area. Civilians, pointing ahead of the Eagle soldiers, warned, "Germans are coming that way!" The Airborne answer was. "We know it -- we're the welcoming committee."

Gen. McAuliffe's order to Lt. Col. Julian Ewell, Ft. Benning, Ga., 501st Parachute Inf. CO, was, "Attack to the east and develop the situation." Shortly after 0900, Dec. 18, contact was made near a small town east of Bastogne, and leading German elements met their first organized resistance, took a bad mauling. During these first confused hours the Medical Company and attached surgical teams were captured west of Bastogne by German armor. Loss of these units was a severe blow to the division. By noon of the following day, 36 hours after the alert, the division established its headquarters in Bastogne and units set up a circular defense of the town. For 24 hours swift-moving German armor and infantry slammed against Bastogne defenses from the east. Each time they were repulsed with heavy losses. Nazis suffered additional grief everywhere they contacted Airborne units. German commanders maneuvered, deciding on a double envelopment from north and south. They had had enough of attacking from the east.

To consolidate lines, the 506th withdrew from Noville on the north while the 502nd occupied Recogne with the support of four TDs. CC R of the 9th and CC B of the 10th Armd. Div., attached to the 101st, repulsed all enemy attempts to break through. Although foggy weather and poor visibility helped them, Germans still were unable to crack the vital road junction town of Bastogne.

Early Wednesday, German panzer, infantry and parachute divisions swelled around Bastogne like a tidal wave, slashed the last remaining road leading into the city, completely surrounded the 101st. That day when Corps called by radio telephone to ask the Eagle situation, Lt. Col. H.W.O. Kinnard, Division G-3, replied: "Visualize the hole in the doughnut. That's us." Everyone was excited about the American hole in the doughnut -- everyone except the 101st. Its fighting men were accustomed to such a situation, expected in any Airborne operation.

The Germans knowing that continuance of their offensive depended on seizure of Bastogne, attacked the complete circle to find a breakthrough point. Field artillery units fought head-on tank advances with point blank artillery and small arms fire. Fog continued to aid German infiltrating attempts. The 705th TD, a crack outfit in any man's army, tore out of its central position time after time to destroy attacking armor. German artillery concentrated on trying to rid Bastogne of the tenacious 101st. On Friday, a new technique was employed. Under cover of a white flag, two German officers entered Allied lines and offered a "Surrender or be annihilated in two hours" ultimatum. Gen. McAuliffe wasted neither time nor words. He sent back the famous answer, with which every soldier was in accord: "Nuts." The German officer receiving the reply was confused -- "I do not understand 'Nuts'." Col. Harper, who handed him the General's reply, quickly explained... "It means to go to hell."

Refusal to surrender meant the enemy might carry out its threat to throw in every available artillery piece. As Gen. McAuliffe said: "They can't have much more than they have already thrown at us. Let it come." It came. But the 101st stuck. Bastogne held firm. Here and there outer lines sagged. German tanks were allowed to infiltrate, infantry following behind were cut to ribbons by Eagle soldiers. Tanks also were given a rousing reception by Airborne doughs and their bazookas, by anti-tank gunners and by tank destroyers. During the siege, 148 tanks and 26 half-tracks were knocked out -- positive indication of the importance Germans attached to the taking of Bastogne. Nazis throw both book and bookcase at Bastogne: armor, infantry, parachutists, Luftwaffe. Night after night, bombers searched out Airborne troopers. Hospitals and troop quarters were hit.

Low-flying dive bombers and heavy artillery were unpleasant and damaging but not unbearable. The 101st stayed on. Complete encirclement of Bastogne placed the division squarely behind the eight-ball for supplies. Airborne artillery long had been accustomed to giving more than it took. Shells now had to be rationed. Artillery waited "to see the whites of plenty of eyes" before letting go. Food became scarce. Screaming Eagles sought clear skies -- flying weather not only for air re-supply, but for planes to keep the Luftwaffe down. Evacuation of wounded became a pressing problem. But they had to wait -- there was no way out of the doughnut. Reports circulated daily that the 4th Armd. Div. was on its way to open a road. Mutual confidence characterized the vicious battle preceding the junction of the 4th and the 101st. Airborne troopers hoped that armor would crack open a path for movement of supplies and evacuation of wounded: the 4th knew that sky-fighters would still be there, killing Germans. It was cold -- freezing cold. Blankets were draped about the wounded. Somewhere, somehow, medicine was found to ease their pain. Hospitals were jammed, floors covered with casualties. Then, the weather began to clear.

To 101st A/B troopers, re-supply is nothing new. It was done on all previous operations. Never before was it so appreciated as on Saturday, Dec. 23, when the first group of C-47s, fuselages jam-packed with supplies, dipped low and roared in. Supply bundles floating to the ground were the prettiest sight Eagle soldiers had seen in many days.

As planes droned overhead, shouts and cheers went up from the men below. Trucks, jeeps, trailers and men crowded the fields a few hundred yards from Division Headquarters in the race to reach the bundles. Every man knew that the arrival of these first planes had broken the German back. Now 101st troopers could go on, supplied by their comrades of the Airborne Troop Carrier forces of the First Allied Airborne Army. Germans attacked again in force the day before Christmas. But it was different now. Throughout the day, hundreds of P-47s roared overhead. In fours and fives, fighter-planes sought out enemy tank and infantry positions. They left burning vehicles and equipment about the perimeter.

Radio-phone reports "tanks knocked out" weren't necessary. The 101st had front-row seats. Christmas Eve, Gen. McAuliffe sent the following message to the fighting men of the 101st:

What's merry about all this, you ask? We're fighting -- it's cold -- we aren't home. All true, but what has the proud Eagle Division accomplished with its worthy comrades of the 10th Armored Division, the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion and all the rest? Just this: we have stopped cold everything that has been thrown at us from the north, east, southwest. We have identifications from four German Panzer Divisions, two German Infantry Divisions and one German Parachute Division. These units, spearheading the last desperate German lunge, were headed straight west for key points when the Eagle Division was hurriedly ordered to stem the advance. How effectively this was done will be written in history; not alone in our division's glorious history but in world history. The Germans actually did surround us, their radios blared our doom. Their Commander demanded our surrender in the following impudent arrogance: "The fortune of war is changing. This time the U.S.A. forces near Bastogne have been encircled by strong German armored units. More German armored units have crossed the River Ourthe near Ortheuville, have taken Marche and reached St. Hubert by passing through Homores-Sibret-Tillet. Libramont is in German hands. "There is only one possibility to save the encircled U.S.A. troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable surrender of the encircled town. In order to think it over, a term of two hours will be granted beginning with the presentation of this note. "If this proposal should be rejected, one German Artillery Corps and six heavy A.A. Battalions are ready to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne.

The order for firing will be given immediately after this two hour's term. "All the serious civilian losses caused by this artillery fire would not correspond with the well-known American humanity." The German Commander received the following reply: NUTS! Allied Troops are counter-attacking in force. We continue to hold Bastogne. By holding Bastogne we assure the success of the Allied Armies. We know that our Division Commander, General Taylor, will say: "Well done!" We are giving our country and our loved ones at home a worthy Christmas present and being privileged to take part in this gallant feat of arms are truly making for ourselves a Merry Christmas.

Shells continued to pour into the "hole in the doughnut." Early Christmas Day, Germans began one of their major attacks. Tanks and infantry broke through in the area of the 502nd and 327th to make it anything but a Merry Christmas. After hours of bitter fighting, the enemy was driven off or wiped out. Eagle lines still held. Close fighter-bomber support helped to erase a large number of German tanks as pyres marked the trail of diving planes. Christmas night, additional attempts were made to bomb Division Headquarters. Constant shelling and bombings reduced the town to rubble.

The rumble of tank fire heralded the approach of the 4th Armd. Div. At 1715, Dec. 26, first elements of the division contacted outposts of the 101st. Minutes later, the gallant Bastogne wounded were evacuated in a long convoy of trucks and ambulances. The 101st maintained contact with the enemy and held firm the same territory it had taken on arriving in the area. Gen. Taylor, having flown back to the battle zone from Washington, resumed command with Gen. McAuliffe's assurance that the 101st was "ready for offensive action." One of many congratulatory messages arriving at headquarters read:

All ranks first Canadian Army have watched with admiration the magnificent manner in which their friends of the 101st U. S. Airborne Division have fought it out with the enemy around Bastogne. Our high regards and congratulations.

And from Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton. commanding VIII Corps:

Dear General Taylor: While this office has recommended that the 101st Airborne Division be cited in official War Department orders for its magnificent stand at Bastogne, Belgium, I feel that I would be remiss in my duty and appreciation without further words on the subject. I desire to take this means of expressing to you and all members of your splendid command my personal appreciation for the superior manner in which the division conducted itself in the action at Bastogne. Without the will and determination of the 101st Airborne Division to stop the superior forces of the German Army thrown against it, there would be a chapter written in history different from the one which will appear...

For 22 additional days, Screaming Eagles held Bastogne as Third Army troops fought their way abreast of the "doughnut." Germans made their last and greatest effort to break the defenses in an all-out attack against the sectors of the 502nd and 327th. These regiments, formed into a task force under Brig. Gen, G.J. Higgins, beat off the assault, inflicting heavy losses.

The division passed to the offensive Jan. 9 and took Noville and Bourcy as its contribution to the advance on Houffalize and final liquidation of the German salient. At ceremonies in Bastogne's bomb and artillery battered town square Jan. 18, five members of the division were awarded Silver Stars, and the mayor presented Gen. Taylor the flag of Bastogne. Reviewing troops after the ceremony, Gen. Middleton, Gen. Taylor and assembled staff officers stood beneath a sign high on the wall of a shell-scarred building. The sign, posted at the junction of four main roads leading into Bastogne, tells the story of the siege in a few simple words. It reads: This is Bastogne, Bastion of the Battered Bastards of the 101st Airborne Division.

March 15, 1945: "Never before has a full division been cited by the War Department, in the name of the President, for gallantry in action. This day marks the beginning of a new tradition in the American Army." These were the words of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, in awarding the Presidential Citation to the heroes of Bastogne, the 101st A/B Division. This is what the citation said:

"The 101st Airborne Division and attached units distinguished themselves in combat against powerful and aggressive enemy forces composed of elements of eight German divisions during the period from Dec. 18 to Dec. 27, 1944, by extraordinary heroism and gallantry in defense of the key communications center of Bastogne, Belgium... "

This masterful and grimly determined defense denied the enemy even momentary success in an operation for which he paid dearly in men, material and eventually morale. The outstanding courage and resourcefulness and undaunted determination of this gallant force are in keeping with the highest traditions of the service."

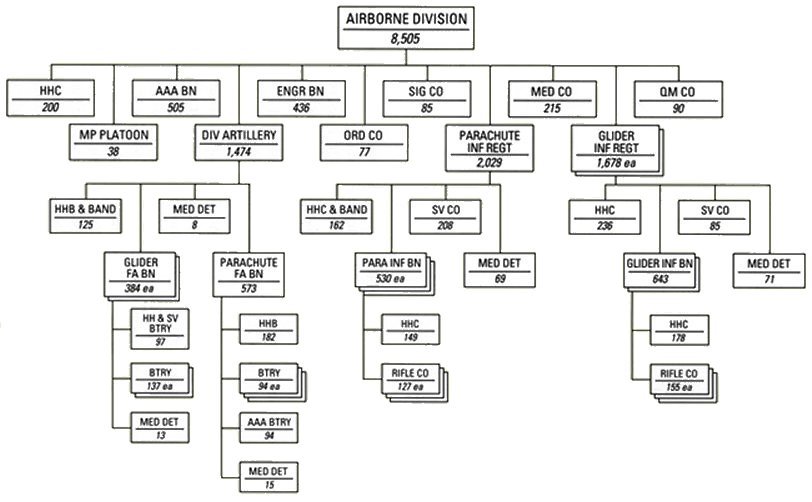

Division Charts and TO&E

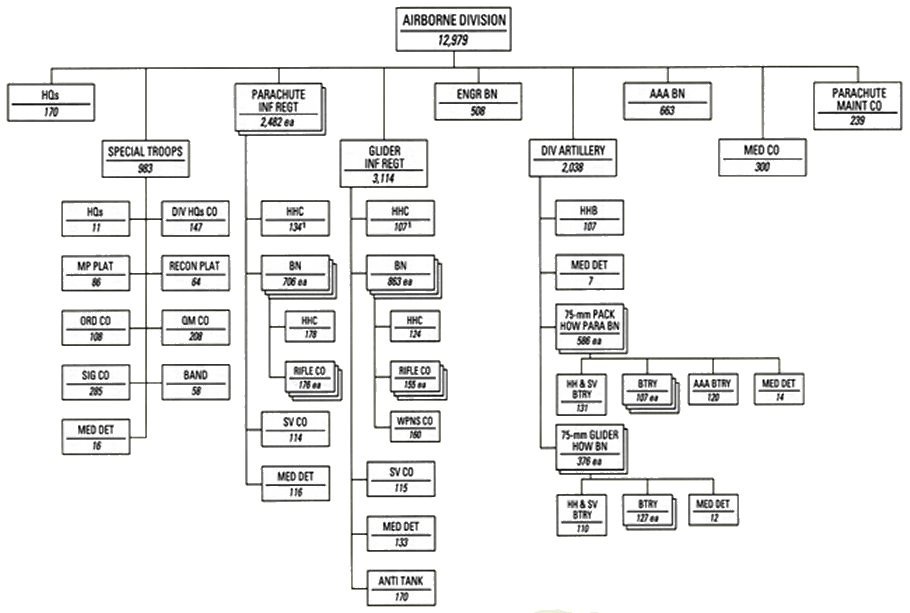

Theoretical Division Chart prior 1944

Theoretical Division Chart since 1944

Follow up by Ken Hesler on my question :

"If I'm not wrong an Airborne Parachute Field Artillery's TO E (as the 463rd, 456th, 377th, ...) consisted of

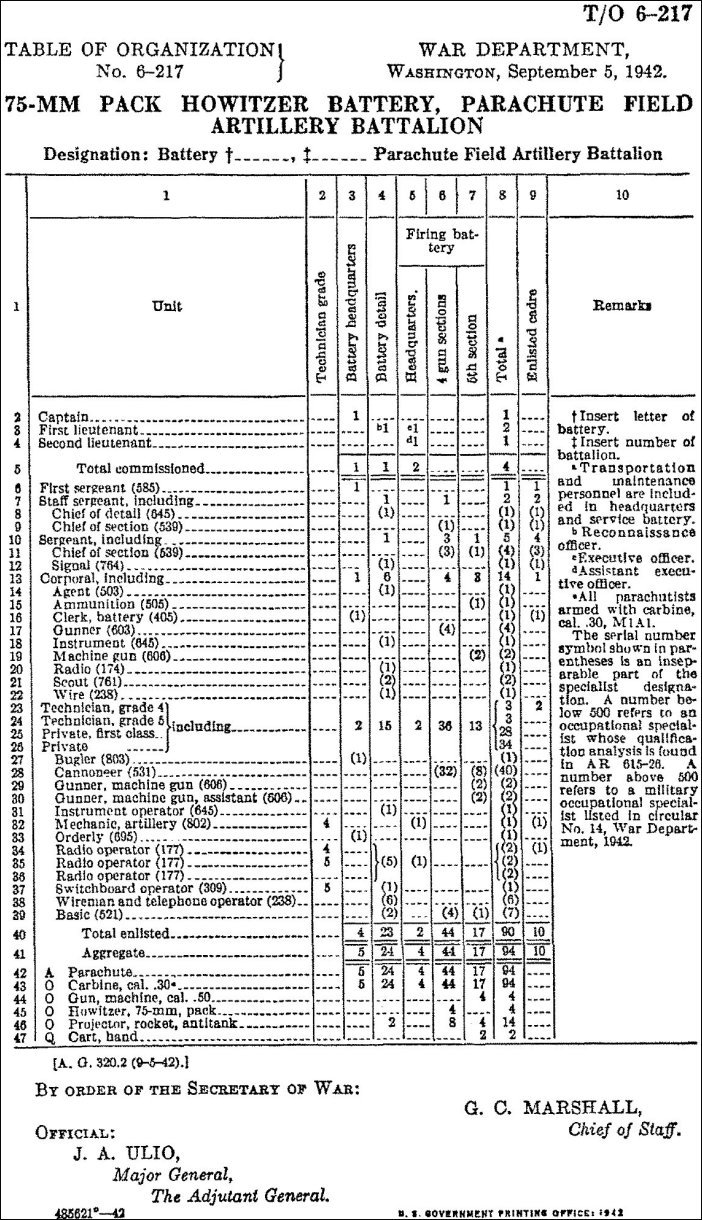

1 HQ Battery (HH & SV, 131 pers.)

3 75mm Batteries, A - B - C => each with 4 x 75-mm Pack Howitzer, M1A1 (one 75mm = 1 gun section, 107 pers. each)

1 AAA Battery, D => with four M3A1 37mm anti-tank guns (120 pers.)

1 Med Det (14 pers.) ?

Ken Hesler:

Filip,

An added note: As you know, the 463rd PFA was organized from Batteries Hq, A, and B of the 456th at Anzio in February 1944, with C and D batteries being reconstituted in July of that year. D Battery was an anti-aircraft and anti-tank unit. It went to Southern France with orders to "furnish all round Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank protection" and to "pay especial attention to repelling enemy reconnaissance parties."

On September 25, 1944, D Battery was reorganized at Jausiers, France, as a fourth howitzer battery with four 75mm M1A1 howitzers.

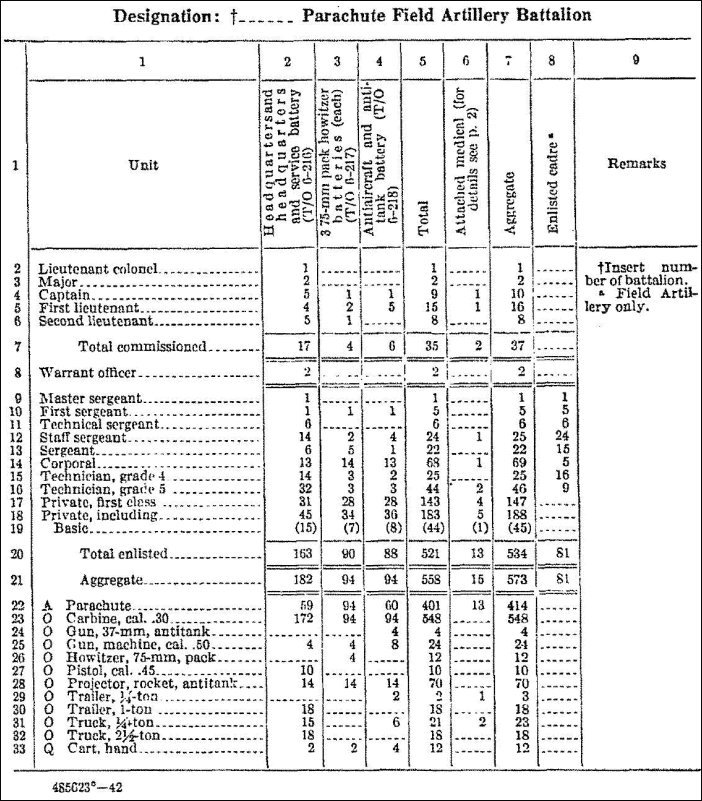

As to personnel numbers, the December 19, 1944, S-1 report on the first day at Bastogne, lists the following

Hq and Hq Btry -- 19 officers, 1 WO, and 167 enlisted.

A Btry -- 5 officers and 91 enlisted.

B Btry -- 4 officers and 89 enlisted.

C Btry -- 5 officers and 97 enlisted.

D Btry -- 5 officers and 93 enlisted.

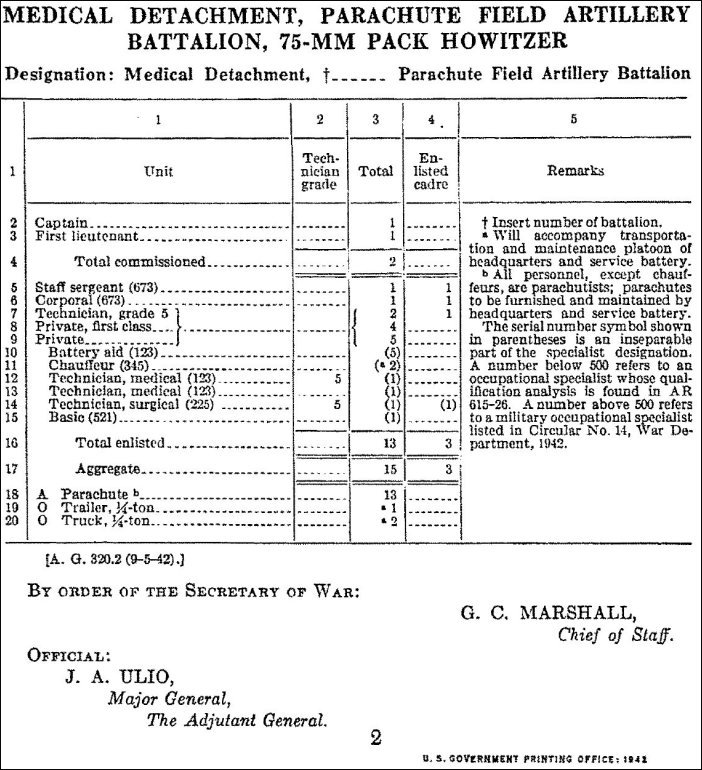

Medical Detachment -- 2 officers and 14 enlisted.

Of course, these numbers varied a bit from day to day, but over time, they are non inconsistent with the organizational charts here above. As for vehicles, the November 10, 1944, (still in Southern France) S-4 report shows a total of 55 vehicles authorized, of which 54 are on hand, with five "deadlined."

On December 22, 1944, the S-4 report has 54 on hand ( 27 1/4 ton jeeps and 27 2 1/2-ton) plus 12 2-1/2 ton attached from 645th QM Company that transported 463rd to Bastogne.

Ken

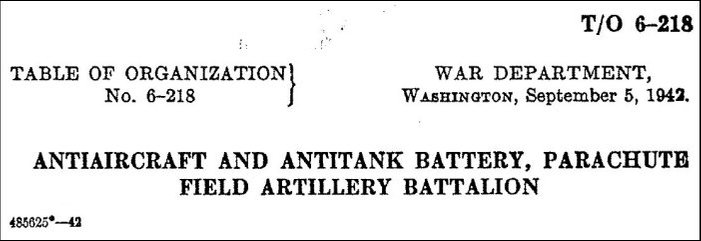

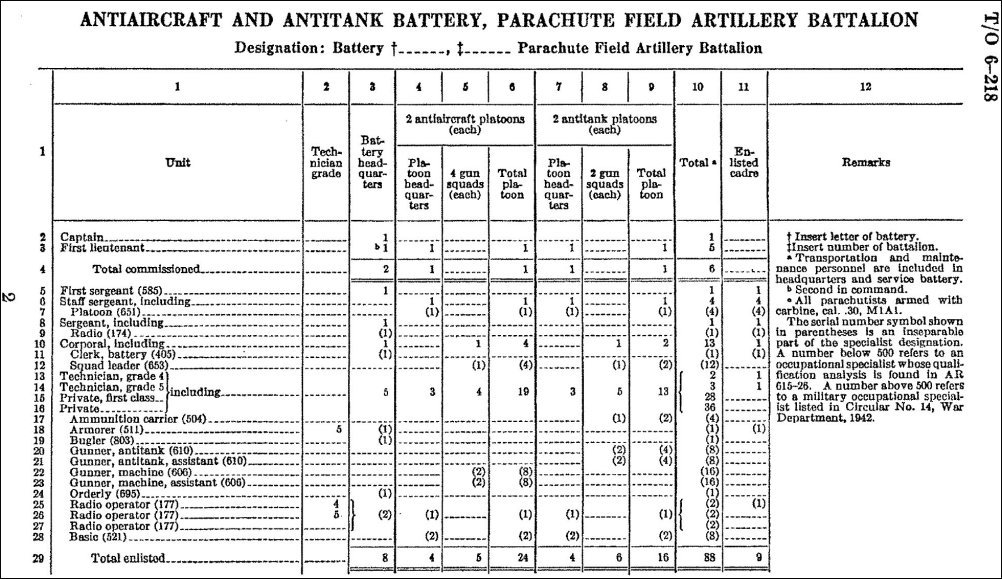

Table of Organization and Equipment (TO&E) - dated 1942

A special thanks to Mr. Matthew Seelinger, Army Historical Foundation (www.armyhistory.org) for providing the information!

Battalion in general

Medical Detachment

The HOWITZER Batteries

The Antiaircraft and Antitank Battery

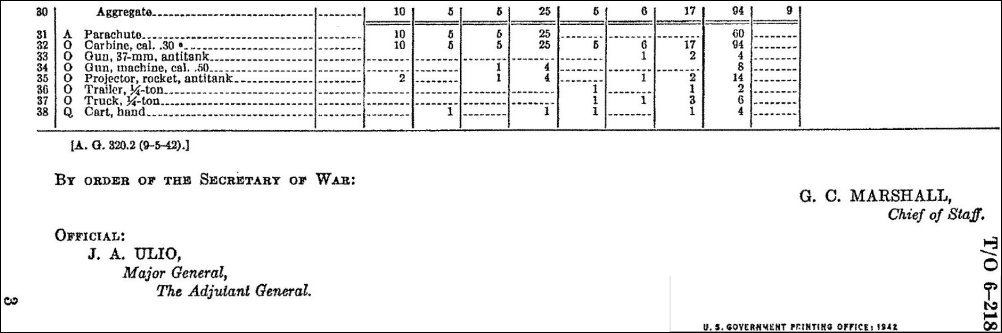

Helmet insignia and basic military map symbols

Helmet insignia used by the 101st Airborne Division

Basic Military Map Symbols

Symbols within a rectangle indicate a military unit, within a triangle an observation post, and within a circle a supply point.

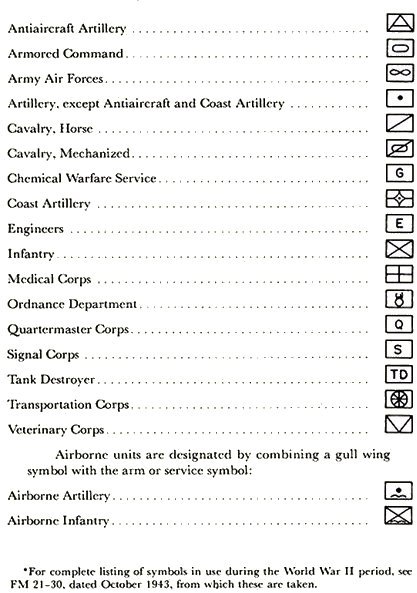

Military Units - Identification

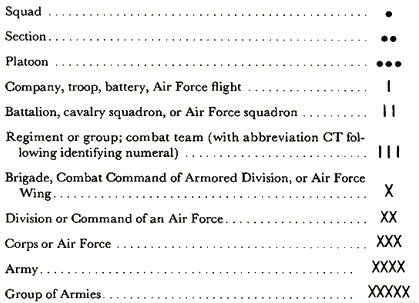

Size Symbols

The following symbols placed either in boundary lines or above the rectangle, triangle, or circle inclosing the identifying arm or service symbol indicate the size of military organization:

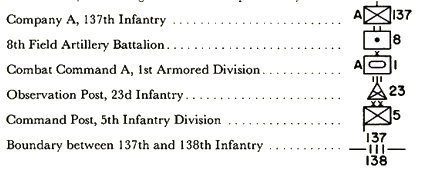

Examples

The letter or number to the left of the symbol indicates the unit designation; that to the right, the designation of the parent unit to which it belongs. Letters or numbers above or below boundary lines designate the units separated by the lines:

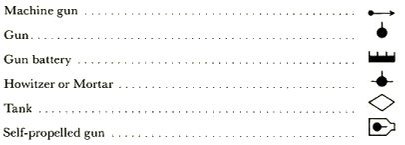

Weapons

Conversions and general information

Various Conversions (Temperature, Volume, Weight, Length, Clothing Conversion...) :

http://www.onlineconversion.com/

United States - state abbreviations :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._state_abbreviations