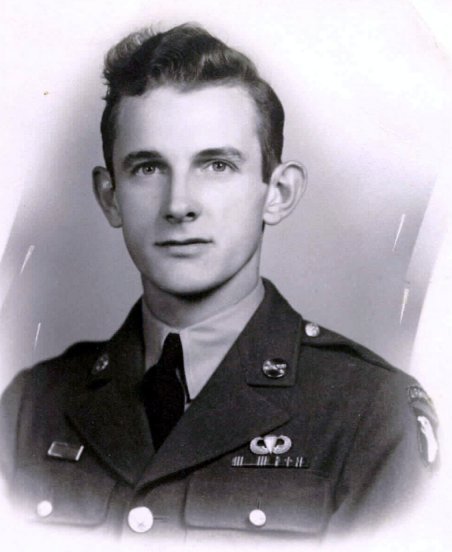

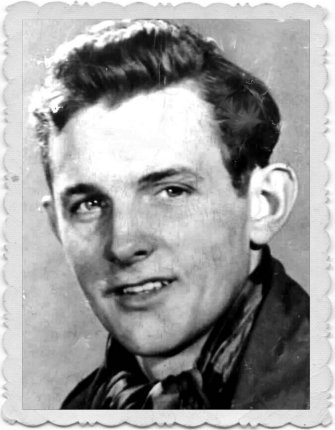

Trooper Private First Class Kenneth HESLER

September 17, 1924 (Greenup, IL)

Photo taken following return to the States in May 1945

I was born September 17, 1924, about two miles north of Greenup, IL, on a small farm, roughly 200 miles south of Chicago, attending a rural school through the fifth grade. The year after my father died in 1934, we moved into town andenrolled in the community schools, graduating from high schoolin May 1942, five months following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Schoolboy to Soldier

I learned about the Japanese attack by radio the day it occurred and, a few days later, listened as President Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Germany and Italy. The only course of action for a young man at that time, of course, was to join the military. I was only 17, but determined to enlist. The first challenge was to convince my mother to sign an affidavit that I was really 18. She finally did when I argued that military service was inevitable and that enlistees could select a branch of service. She signed, and I took the oath in the U. S. Army on June 6, 1942, at Chicago, IL. All my military records indicate that I was born in 1923, not 1924.

As promised, I asked for the Coast Artillery and got it, departing soon by train from Camp Grant near Chicago for Fort Totten, New York, and the 62nd Coast Artillery Battalion (Antiaircraft) – later Battery E, 893rd AAA-AW Battalion. My basic training site was in downtown Manhattan, a fenced-in parking lot alongside the East River with rows of pyramidal tents.

At first, we drilled with M1903 bolt-action Springfield rifles, World War I style dishpan helmets, and practiced gunnery on chalk-outlines of pretend 37mm antiaircraft weapons. After a few weeks, we received M1 helmets and M1 Garand rifles. When Basic ended, I briefly stood shifts on a 50 cal machine gun post atop a 17-story office building at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Not long thereafter, we were told that we were going overseas.

The 37mm guns were replaced with rapid-fire 40mm Bofor antiaircraft weapons. Soon we were off to Camp Kilmer, NJ, preparing to embark.

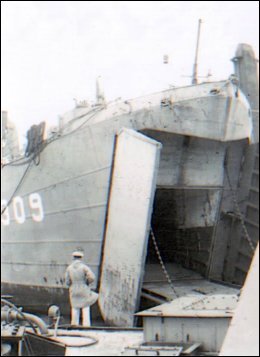

The LST 309

On August 6, two months after my enlistment, we sailed from Pier 16 at Staten Island for Halifax, Nova Scotia, and thence to Glasgow, Scotland, making that voyage in the converted Matson liner SS Monterey. Ironically, that was the same ship on which the 456th PFAB (from which the 463rd was organized) would cross the Atlantic to North Africa less than a year later with the 82nd Airborne Division.

We moved by train and truck to England’s Salisbury plain, a major military training area, about 50 or so miles from London, to prepare, although we did not then know it, for the November invasion of North Africa, digging foxholes in the hard chalk, taking long marches, and again doing duty on a 50 cal machine gun atop one of the towers of Longford Castle near Salisbury. Finally, we traveled to the coast of windy Cornwall for practice with the 40mm, where I trained as a gunner and electronic tracking operator.

We shipped from Glasgow in late October 1942, aboard the SS Argentina, going ashore at Mers el Kebir, near Oran, Algeria, in early November. After an eight-month campaign during which I was promoted to PFC, we boarded LST 309 at Bizerte, Tunisia, for a rough ride to Licata, Sicily, and the invasion of that island in July 1943.

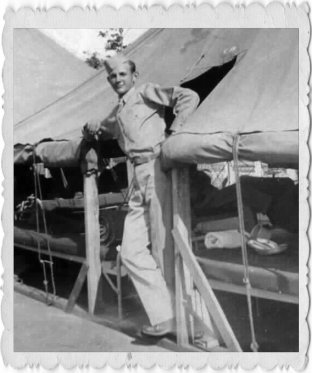

Basic training in Manhattan, NY parking lot, July 1942

On duty at 40mm Bofors antiaircraft site near Bizerte, Tunisia,

prior to invasion of Sicily in July 1943

with 893rd AAA-AW Battalion.

Settling Down in Palermo, Sicily

In Sicily, we followed General George Patton northward to Palermo, arriving in that city the day after it fell. And there we sat with an occasional German air raid until the spring of 1944 -- one six-hour pass a week and an infrequent opportunity to visit the U.S. Army hospital in Palermo to donate blood for $10 a crack and a shot of Red Label whiskey. Under Gen. Patton in Sicily, a soldier caught not wearing leggings could be fined $25, along with his commanding officer. The 62nd was a competent organization, mostly with middle age pre-war officers, composed of eight guns (crew of 15 men per gun) with guard shifts 24/7 -- four hours on and eight hours off. To put it frankly, the war had become boring.

The Airborne Comes Calling

In early spring 1944, recruiters visited the unit to interview soldiers with combat experience and high school math backgrounds for possible airborne training. If my memory is correct, about 20 of us accepted the opportunity. Three of us survived the four-week jump training and were assigned almost immediately to the 463rd. My destination was the Communication Section of “D” Battery.

Sgt. Charlie Keller of York, PA, was the section sergeant. Among those in that group that I recall were George Blair, Chattanooga, TN; Louis Probst, Long Island, NY; Ernie Porter, Falmouth, ME; Joe Boudreau, Plainville, CT; and Tom Mullen, Brooklyn, N.Y. As a lineman, I went to war armed with wire cutting pliers, a pocket knife, a roll of tape, and an EE-8 portable telephone, often running in and out of ditches behind a 3/4-ton truck dispensing wire along the side of a roadway.

On occasion, I operated a 12-line switchboard or, more often, set off along a stretch of wire looking for a line break, stopping from time to time to make an alligator clip connection with the other end and then, when successful, back tracking to find the break and make the repair. In the Maritime Alps, “D” Battery became a 75mm firing battery. I graduated a bit, back-packing a radio on an A-Frame with forward observation parties up winding mountain hillsides, sometimes scrambling beyond where mules could not go.

The Great Battle of Jausiers

On the night of October 15, 1944, the 463rd fired more rounds than in any other mission during World War II, as I learned after the war, in what we came to call the “Great Battle of Jausiers. Col. John Cooper, Battalion Commander, later reported that mission this way -- “Halfway through the month of October, the Germans launched a late evening attack aimed at securing two strategic peaks. By firing five thousand six hundred (5,600) rounds of direct fire on the peaks, the attack was repulsed and the enemy driven back.”

French Riviera to Frozen Bastogne

As winter approached in late October, we left Jausiers for the Menton area to support the First Special Service Force, being relieved in mid-November for a brief bivouac in Gattiers near Nice before heading north to Mourmelon and the 101st for a few days of indoor living and warm showers.

My trip from Mourmelon to Bastogne was in the rear of a tarp-covered 2-1/2-ton truck manned by a Red Ball Express driver and loaded with five-gallon cans of gasoline with seven or eight of us scattered about on the wood benches. It was a night of fitful sleep with my legs stretched across the gasoline cans. The trip seemed to last forever, particularly as our part of the convoy took a wrong turn and had to do an about face. Upon arriving in the Bastogne area near Flamizoulle, we assembled along the road among a plot of young trees and dug foxholes, positions we assumed until we moved on later in the day to Hemroulle.

With the 101st surrounded at Bastogne and “D” Battery set up to fire in a 360-degree circle, the demand for forward observation teams was ongoing. As a result, the Communication Section maintained a more or less regular schedule of three FO days out and three days back in the Battery area. As a result, I spent considerable time at Bastogne on FO duty as a telephone/radio operator, mostly the former.

Nice, France, 1944

Hemroulle

Among my various Battery area duties were (1) foraging to find a stove and fuel for the warming tent, along with carpeting material for the floor and door flap of my rarely-used log foxhole dug into the side of a wooded ridge, (2) venturing out into the surrounding area during the early foggy days as one of several two-man bazooka teams in search of enemy intruders but encountering none, (3) digging a bazooka hole on the south side of the Bastogne-Hemroulle road that we manned regularly, and (4) huffing and puffing while running in an overcoat through foot-deep snow to repair breaks in telephone lines.

I was in the battery area and took part in recovering supplies during the first relief parachute drop on December 23. On Christmas Eve, I attended services in the barn near the Battalion CP in Hemroulle, and then did sentry duty along the Hemroulle road during shifts from 8-10 p.m. and 2-4 a.m. During the early shift, I witnessed the bombing attack on Bastogne with its accompanying display of aerial flares and, in the early morning, heard the bombs falling near Champs.

It was eerily quiet and cold when I curled up after 4 a.m. in my sleeping bag at the warming tent alongside the Bastogne-Hemroulle road, removing only my overcoat and shoe-pacs to dry the felt insoles. Sometime later, I was startled as all hell broke loose in the area. Hastily donning boots and overcoat, I grabbed my carbine and ran, with others, to a ridge alongside the road, assuming a defensive position facing the firing sounds, but we could see nothing. My other memory of that Christmas Day was a meal of two hot pancakes sprinkled with sugar.

It was also from the bazooka hole on another day that two of us watched as one of our 50 cal. machine gunners atop a small hill north of the road let go a burst at two planes overhead that just happened to be friendly. They reacted by circling back and dropping two bombs that could be seen clearly arcing toward the ground. No one was hurt. Hasty shouts for the display of recognition panels accompanied the event.

FO Expeditions, Here and There

Observation parties always began in roughly the same way. Whether rainy, foggy, or freezing cold, I would find myself in a jeep with musette bag and bedroll riding through the countryside with no idea of where we were going. I do not remember the lead observers, other than Lt. Jack West and Sgt. Keller.

With limited exceptions, these trips were about the same. Our jeep would pull off the roadway, into an area of scrub brush where a few other vehicles were already parked and walk into the edge of a dark pine woods with a wet carpet of needles or snow underfoot. Eventually, we would come upon a small group of infantry inside the outer edge line of the woods, beyond which, a few hundred away, the enemy kept within the cover of another forest. I do not recall needing to lay any wire on these missions as the first task was always to find our tagged wire wrapped around a tree trunk, attach the telephone, and make contact with Fire Direction Center.

Two of us would dig a two-man sleeping foxhole. More often than not, the first fire mission was to register the guns with smoke and stand by for visible targets or others relayed by the infantry. My usual task, was to man the telephone and repeat the observer’s words back to the Fire Direction Center.

Occasionally, harassing enemy artillery or mortars were fired into our area; and at night, the chatter of machine guns and the explosions of artillery could be heard in the distance. Two memorable events occurred on these missions, both of them in the days shortly after Christmas.

One of them involved a glider bearing doctors and medical supplies landing nearby in an open area to the right of our wooded position. As those on board came dashing into the woods, small arms fire could be heard among the treetops. After being told what that noise was, they dashed off hastily to the rear. It was then that the lieutenant in charge of our party directed me and two others to “Get out there and unload that glider.” I was first into the craft and began passing bundles along to the others who were scurrying back and forth to the edge of the woods. It is surprising how “strong” one can be under those circumstances. We were wary that the Germans could see us and awaited some reaction, but nothing happened.

The other well-remembered event took place sometime near the end of December and not long before the Germans departed the Champs area, when our FO party quartered on the second floor of the Rolle Chateau. The observation post was atop a nearby ridge with a good view of the area north of Champs. It was a narrow, two-man hole with seats dug into opposite sides and just room for two persons to sit below ground level, with only the radio antenna protruding.

One cloudy afternoon, Sgt. Keller and I watched as about six American armored vehicles set out across an open field to our left, firing one or two rounds into each of a series of haystacks as they advanced, until the enemy returned fire from an unseen location, crippling at least two of the vehicles before the others scuttled away in reverse. Later that night, Sgt. Keller crawled out of the hole and said he was off to see what he could find aboard the damaged American tanks, leaving me alone to wonder how I could identify him on his return. Teaming up with Sgt. Keller was always an adventure.

A second event at Rolle Chateau occurred when I was alone in our bare second-floor quarters, awaiting the delivery of the evening meal by way of a ¾-ton truck and insulated mermite container. My task was to “prepare” dinner by heating one of the pans filled with meat, potatoes, and gravy, a rare delicacy at Bastogne. The single-burner Coleman stove was warming the food near a window when two rounds of enemy artillery fire exploded in the courtyard not far from the window. Glass shards fell all around the stove and, as far as I could tell, into the food container.

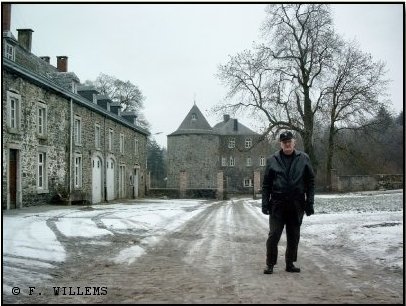

Ken at Chateau Rolle in 2004.

At left are the FO second-floor quarters.

Faced with the immediate quandary of how to deal with this “precious” food before the others returned, I found a quick and simple answer. Taking an undershirt from my musette bag, I dumped the container of food into my metal helmet and, using the shirt, carefully wiped clean the pan and each piece of meat and potato to insure the absence of glass. To finish the task, I strained the gravy back into the pan through the shirt and began reheating the meal. I do not recall how I disposed of the shirt, but all unknowingly enjoyed the fare.

On January 11, a Thursday, I learned that I was among those to receive a 48-hour pass to Paris over the coming weekend, leaving the 12th and returning the 15th. Under an open tarpaulin shelter on that same day and in the freezing weather, I took my first bath in several weeks, unclothed, and with one foot after the other in a bucket of warm water. The following day, we rode in a convoy of a jeep and two open 2 ½-ton trucks for nearly four hours, sitting huddled inside our sleeping bags. Our destination was the Rainbow Corner Red Cross club located in the Hotel de Paris on the boulevard de la Madeleine.

Bill Kummerer and I, both of “D” Battery, shared a room on the second floor. On the second night we rode the Metro to Place Pigalle and spent the night accepting champagne from a group of Air Force officers at Club Eve, somehow making it back to the hotel in the early morning walking through the cold streets and alleys of Paris. The following day, we returned to the Battalion to find that it had left Hemroulle and taken up a position near Recogne.

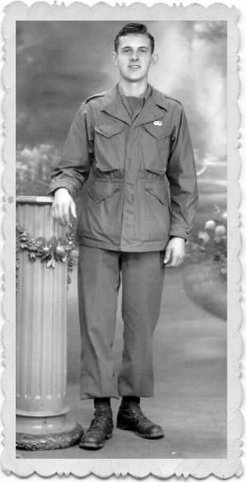

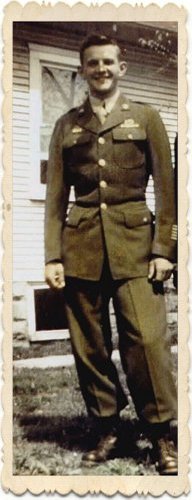

Picture at left :

#4-Forty-eight-hour leave to Paris January 12-15, 1945 at Red Cross’ Rainbow Center, Hotel Paris. Pass noted “No blouse issued,” so field jacket and camouflage chute scarf were fine.

Moving Indoors

It was not too many days later that the Battalion, mostly in covered ten-ton trucks with straw on the floor, moved south with the Division over slippery roads to Keffendorf in the Alsace region and, several days later, on to Wintershouse near the Moder River. It was there that I was assigned to Fire Direction Center, sitting around a table in a local school house working the telephone for “D” Battery under the direction of Maj. Vic Garrett, Battalion S-3. My quarters were nearby on the second floor of a half-timbered house where I resided until we returned by train to Tent City at Mourmelon.

Ken Hesler : "A scene in the Fire Direction Center in Alsace (Winterhouse).

In the photo, I am the third from the left.

I knew the others in the photo a relatively short time and do not recall their names

although they all look familiar. They are from the other batteries.

Each of us handled phones to the respective batteries during fire missions.

Maj. Vic Garrett was in charge of the operation.

You can see we were playing cards during a lull in activity."

A Brief Stay in Tent City and Off for the USA

A short time after our return to Mourmelon, we rehearsed in full dress uniform for the Presidential Unit Citation ceremony, preparing for Gen. Eisenhower’s visit on March 15, but I did not remain with the 463rd for that grand occasion. Following a stint of guard duty over general prisoners unloading a freight train, I reported back to the Battery CP to return my clip of ammunition where an officer asked if I wanted to “Go home to Greenup, Illinois.”

Unaware at the time that I had hit the 85-point rotation level on the Advanced Service Rating Score (ASR) after being overseas nearly 32 months, I was surprised but readily accepted the offer. Along with a number of others from the Division, we left Mourmelon by truck on March 12 for Le Havre, France, where we loaded aboard the SS Marine Robin for the trip to the USA on 30-day “temporary duty” leaves. I made it home April 8, hitch-hiking the last 30 miles with my barracks bag compliments of a truck driver who rerouted his trip. When the war ended, my leave was extended to 45 days, after which I was discharged May 28 at Fort Sheridan north of Chicago.

Life After the 463rd

After one year of college under the G.I. Bill, I decided to make the Army a career, and re-enlisted for 18 months with the 3rd Armored Division at Fort Knox, KY, where I was promoted to Sergeant and assigned as permanent party in Headquarters, Headquarters Company. While there, I taught in the Division’s cadre school, the Universal Military Training Experimental Unit, and assisted in the development of lesson plans for other training centers until the end of my enlistment in November 1947. Rather than re-enlist, I returned to college upon the advice of my commanding officer, receiving a diploma from Eastern Illinois University in June 1951.

Following graduation, I began a 33-year teaching and administrative career at the same institution, at first in an acting position for a person on sabbatical leave. I earned a Master’s degree from the University of Illinois and later did advanced study there in Mass Communications and American Literature. I met my wife at the university. We will celebrate our 60th anniversary December 22, 2011. We have one daughter.

In the late 1970s, Joe Lyons, Cecil Farmer, and I, among others, made an effort to find former unit members for our first reunion at Nashville, TN, in 1980. In recent years, several of us have worked with Filip Willems in Belgium to establish and maintain the 463rd website, relying, in part, on the more than 2,000 pages of Battalion records I obtained from the National Archives in 1987 that document the day-by-day operational history of the Battalion from February 1944 through October 1945.

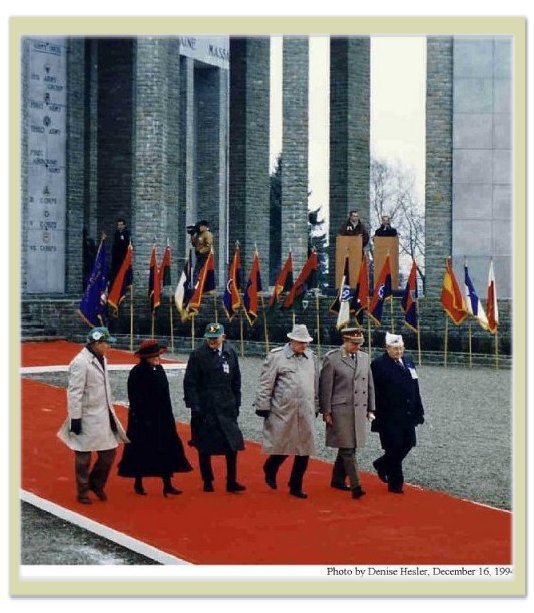

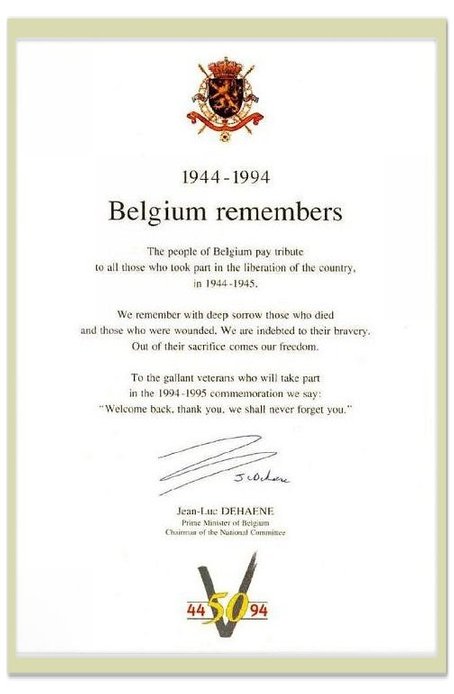

I retired as Director of University Relations and Advancement at Eastern Illinois in December 1984. Since then, I and my family have traveled on several occasions to the battlefields of Europe, including serving in 1994 as one of two 101st veterans escorting U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright at the Commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge. I have been active as a member of the 101st Airborne Division Association since the middle 1980s in the areas of finance, membership, and public affairs.

Kelly Stumpus, left, and Ken Hesler, third from left, both veterans of the 101st Airborne Division, escort U.S. Secretary of State Madeline Albright, second from left,

at the 50th commemoration of the Battle of the Bulge wreath laying in December 1994.

The site is the Mardasson Bulge Monument just outside of Bastogne, Belgium.

Two other Bulge veterans at right escort King Albert II of Belgium for the ceremony.

Reflections

Like most soldiers barely beyond their teens, we were imbued with an inherent belief that we were immortal. That is why the young are called upon to fight wars. But that saving grace did nothing to ease the conditions of the soldier in wartime – insufferable boredom, blistering heat, freezing cold, soaking rain, homesickness, weariness, hurrying up to wait, and learning to live with fears from which one cannot flee.

As we grew older, we lost that youthful sense of immortality but gained the nostalgia of the survivor. Sure, the war was bad, but we had some great times. We had numerous once-in-a-lifetime experiences and saw a great deal of the world. For a depression era kid, the food was pretty darn good. And those wartime buddies with whom we shared both danger and laughter became friends for life. Despite all its hardships and dangers, World War II was the most significant factor in shaping my life, aside from family. As for service with the 463rd, although often difficult, it was in retrospect an experience that I have long treasured. The hallmarks of the unit were high morale, dedicated soldiers, and first-class officers.

Prior to the war, I was heading no place. I did janitorial work at my local school, delivered newspapers, sold muskmelons from a hand-pulled wagon, collected and sold scrap iron, and worked as a clerk and apprentice butcher in the local grocery store. The major job opportunity for adults in the community was the local shoe factory. My highest salary at the grocery store for a full six-day week of summer work was $15. Higher education was not an option or even a thought.

The war forced upon me, in just three years, a level of maturity and sense of responsibility not otherwise achievable. It gave me the G.I. Bill, an educational ticket to a new life and a step up the ladder. Most of all, my war experiences, particularly with the 463rd, gave me a sense of pride and an everlasting conviction that I had done something that was special, that really mattered, and that actually made the world a better place, however small that contribution may have been.

Thank you Mr. Ken Hesler for the interview and the friendship, and also for all the info on the 463rd you provided.