Trooper Lieutenant-Colonel John T. COOPER, Jr.

August 19, 1913 (Checotah, OK)

ALL PICTURES : Courtesy of the Family

Education

LTC John T. Cooper Jr. was born in Checotah, Oklahoma on August 19, 1913 to John T. and Laura Robinson Cooper.

He graduated from Wewoka High School in 1931 and from the University of Oklahoma Law School in 1938. He practiced law with his father, John T. Cooper, Sr. subsequently for two years in Wewoka before entering military service. Cooper married Alice Knight of Wewoka in 1939.

Experience

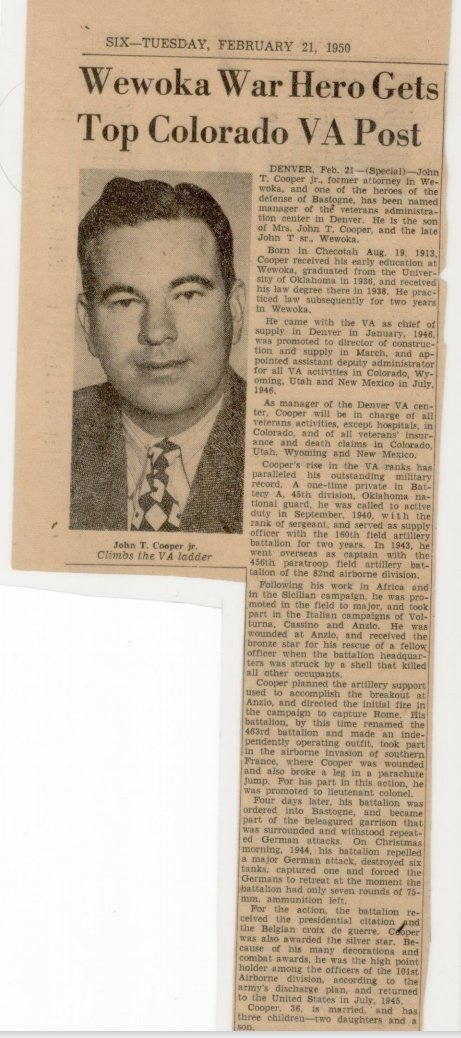

John T. Cooper was an attorney in Wewoka, and one of the heroes of the Defense of Bastogne.

After the War, he was recruited by General Omar Bradley to work with the Veterans Administration as Chief of Supply in Denver in January, 1946. Cooper was promoted to Director of Construction and Supply, and then appointed Assistant Manager for all VA activities in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. In 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower became President and selected Cooper as Manager of the VA office in Manila, Philippine Islands where he served until returning to private law practice in Wewoka in 1957. In 1968, Cooper and his family moved to Duncan, OK where he served as First Assistant District Attorney for 4 counties until his retirement in 1978. During retirement, Cooper became active in the 101st Airborne Association, and he was elected President of the group in 1988. He and his wife Alice enjoyed attending 463rd and 101st reunions throughout his retirement.

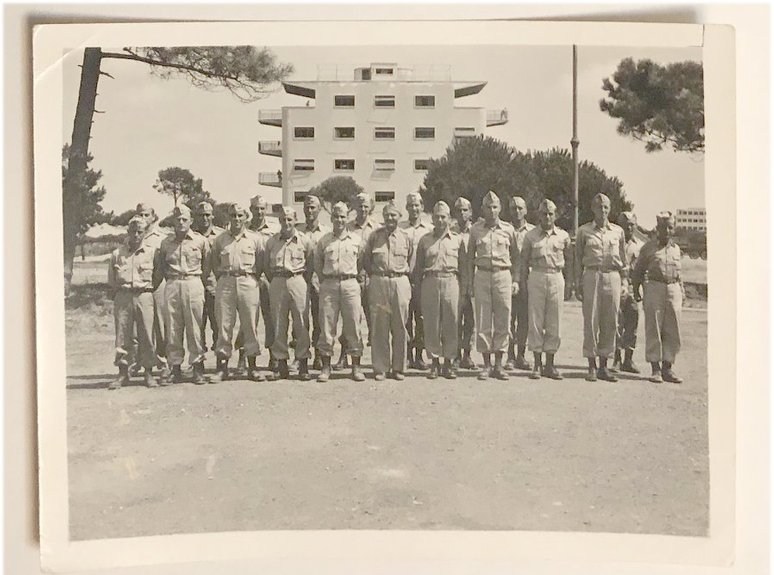

Military : the Beginning.

John T. Cooper's rise in the VA ranks paralleled his outstanding military record. A one-time private in Battery A, 45th Division, Oklahoma National Guard, he was called to active duty in September 1940, and commissioned as a Lieutenant. He served as Supply Officer with the 160th Field Artillery Battalion for two years. In Dec. 1942, he applied for parachute training and was assigned to Ft. Benning. In 1943, he went overseas with the 82nd Airborne Division to North Africa as Captain, serving as Executive Officer with the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, attached to the Canadian American First Special Services Forces.

First Campaigns

Following his work in Africa and the Sicilian campaings, he was promoted in the the field to Major, and took part in the Italian campaigns of Volturna, Cassino and Anzio, and recieved the bronze star for his rescue of a fellow officer when the battalion headquarters was struck by a shell that killed other occupants.

John Cooper planned the artillery support used to accomplish the breakout at Anzio, and directed the initial fire in the campaign to capture Rome. His battalion, by this time renamed 463rd Battalion and made an independently operating outfit. In February of 1944, one half of the 456th was sent to England, and John Cooper became part of this newly created 463rd Parachute Field Artillery unit which remained in Italy and was assigned to the 5th Army. Serving as artillery support for Brigadier General Robert Frederick, Major Cooper took command of the unit during fighting at Artena.

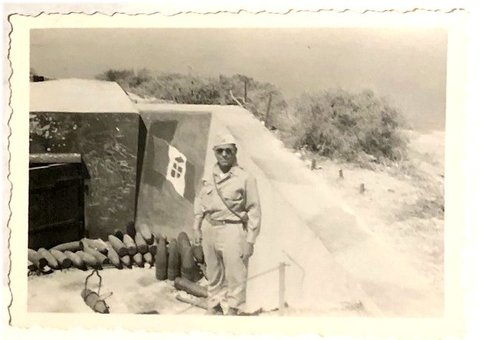

Italy : entrance to Pill Box

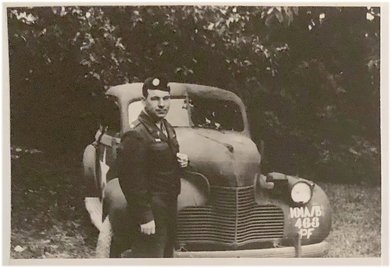

John Cooper, East of Airport of Comiso, September 1943

Rome, then Dragoon, France

Now in position to liberate Rome, the 5th Army advanced and the 463rd was one of the first units to enter the Eternal City. In June of 1984, during the 40th anniversary celebration of that action, John Cooper with members of the 463rd, assisted Senator Robert Dole in representing the United States in the placing of a commemorative plaque at St. Paul’s Gate in Rome.

After the action in Italy, John Cooper’s 463rd prepared for the invasion of Southern France, and made the jump in France on August 15, 1944. He was injured in that action, when he broke a leg in the parachute jump, but returned to command his unit after six weeks. The 463rd worked its way up the coast toward Nice with General Frederick and the First Special Service Force. For his part in the action, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. The task force disbanded in November of 1944, and the 463rd was then attached to the 101st Airborne Division for administration and rations. The main body of the 101st had prior been sent to Holland. Now the 463rd was placed on alert in France after the German breakthrough in the Ardennes on December 16, 1944.

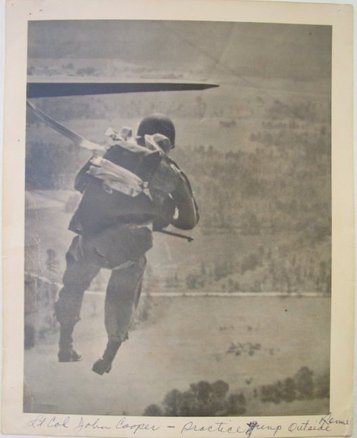

Officers At Lido di Roma, upper left is LTC J. Cooper.

Middle is Maj Seaton, right is Major Garrett.

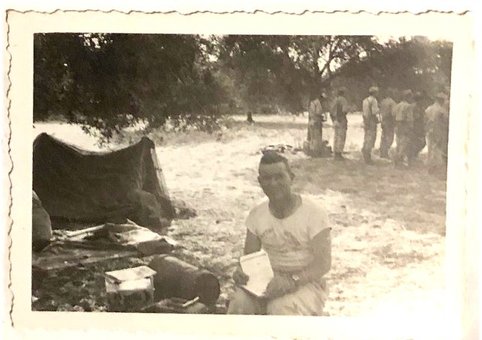

Practice Jump in Rome

Front Row

Wright - Milne - Moran - Gerhold - Garrett - Neal - Cooper - Seaton - Cole - Laidlaw - Rozen

Back Row

Kirchner - Martin - Mury - Lyons - Merriman - Kranyak - Smithers - Toffany - Maire

Family

LTC John T. Cooper and his wife, Alice, had five children, two daughters and three sons. Cooper died Dec. 17, 1999 and is buried in Ft. Sill National Military Cemetery, in Lawton, Oklahoma.

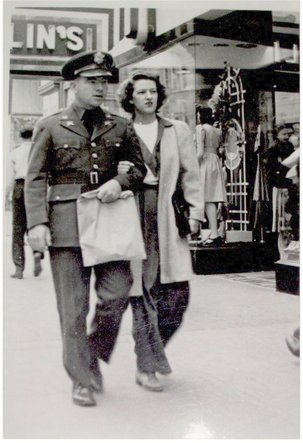

Probably around 1940:

Mr. Cooper and his wife Alice

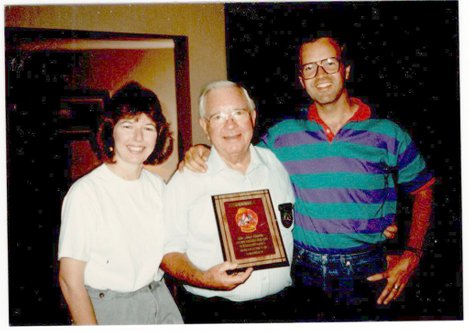

Probably at the reunion in Omaha, Nebraska. Mr. Cooper is holding the 463PFA patch. On the left is his daughter Melanie and on the right his oldest son Robert (Bob)

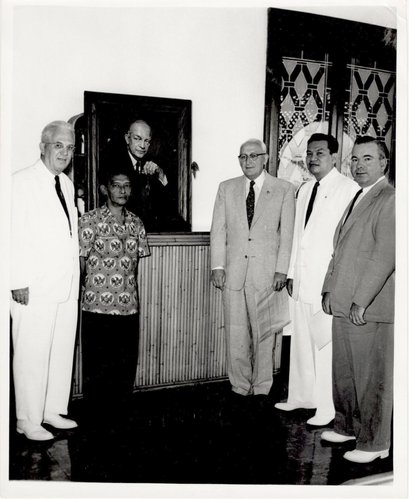

Taken when Mr. Higley (U.S. Head of the VA--to right of Eisenhower picture ) visited Manila to meet with Mr. Cooper and Philippine President Magsaysay (between Higley & Mr. Cooper) about the VA hospital Mr Cooper was building there.

Ferguson on the left was probably the head of the hospital staff, but not sure, he may have been someone with Higley from D.C.

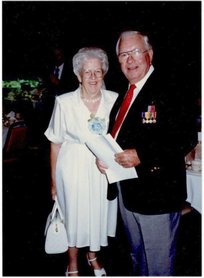

Mr. and Mrs. Cooper

101st Reunion at Omaha in August 1988

Cooper - Neal - Karp (Rear) - Seaton - Fuller - Rogan - Vic Garret (seated). Mr. Cooper was then President.

Battle of the Bulge , War's End and Beyond

Four days later, LTC Cooper and his battalion left Mourmelon, France, and were ordered into Bastogne to provide artillery support to the 101st units, thus becoming part of the beleaguered garrison that was surrounded and withstood repeated German attacks. Having operated as an independent artillery support unit, John Cooper’s 463rd was better supplied than many of the 101st artillery units. Fortunately, the 463rd had obtained armor piercing ammunition which became very useful. In the pre-dawn hours of Christmas morning, the Germans launched a second all-out attack intended to wipe out the Bastogne pocket. Evidently mistaking the town of Hemroulle for Bastogne, the German infantry team with eleven tanks headed unknowingly right for the 463rd. Their stopping point was only about 100 yards from Cooper’s 463rd howitzers which were virtually invisible because of the darkness combined with a recent light snowfall. Incredibly, the German column remained in this position for over an hour. Lt. Col Cooper ordered fire be held as long as possible to provide positive identification and increase hit probability in the light of dawn. When the command to fire was given the battle ensued and many of the 463rd men fought as infantry. Eight tanks were knocked out and 1 other was captured.

During the period 19 December to 31 December 1944, the 463rd fired over a 360 degree sector, expending a total of 7676 rounds of ammunition on almost every kind of target. For this action, the 463rd battalion received the Presidential Unit Citation.

After the Battle of Bastogne, General Maxwell Taylor interceded to have the 463rd remain with the 101st and it did so for the rest of the war, including the Rhineland Campaign. Because of his many decorations and combat awards, John Cooper was the high point holder among the officers of the 101st Airborne Division, and according to the army's discharge plan, eligible to return to the United States in July, 1945. Lt. Col Cooper ended his service in Europe as the military governor of the town of Bad Reichenhall, Germany, just outside of Berchtesgaden (Eagle’s nest). Lt. Col. Cooper officially separated from active duty military service in November 1945.

With General Bradley

With the Dietrich sisters at Mourmelon

The House in Bad Reichenhall where Lt. Col. Cooper lived.

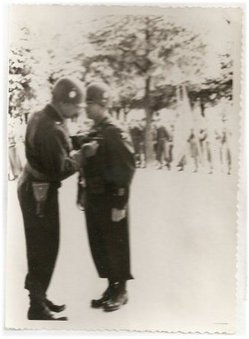

Receiving an Award

LTC Cooper was awarded the Silver Star and the Bronze Star with oak leaf cluster and the Purple Heart with oak leaf cluster, the Belgian Croix de Guerre and the Croix de Guerre from France in addition to a host of other service medals. He retired from service in August, 1973.

After the war, John Cooper served with the U.S. Veteran’s Administration until 1958 holding positions at the Denver regional office and then, as mentioned above, as manager of the V.A. office in Manila, Philippine Islands. Upon returning to the States, Mr. Cooper and his family settled in Wewoka, Oklahoma where he practiced law for ten years before moving to Duncan, Oklahoma in 1968.

John Cooper served the counties of Stephens, Jefferson, Grady and Caddo as first assistant District Attorney from 1968 until his retirement in 1978.

Mr. Cooper was a fifty year member of the Oklahoma Bar Association and a member of the First Christian Church in Duncan.

Military Service

Second Lieutenant, Reserve Corps, Oklahoma University: 1936

Resigned Lieutenant's commission: 1938. Enlisted in Battery "A", 160th FA Regt.

Oklahoma Nat'l Guard as Private. Private, Corporal, Sergeant: 1940.

Commissioned Second Lieutenant, Nat'l Guard: June 1940.

Promoted First Lieutenant: Sept 9, 1940.

Inducted into Federal Service: Sept 16, 1940.

Promoted to Captain: January 1942.

Promoted to Major: October 1943.

Promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel: November 1944.

Departed overseas: April 29, 1943.

Arrived U.S.: July 1, 1945.

Member of 45th Division: Sept 16, 1940 to December 1942.

Member of 463rd Parachute Fld Artillery and later 101st Airborne Division: 1943 to date of discharge.

Went overseas with the 82nd Airborne Division.

Made parachute invasion of Sicily and France. First Artillery Battalion in military history to make an invasion by parachute (Sicily).

Decorations

DECORATIONS

Purple Heart : Anzio

Bronze Star : Anzio

Oak Leaf Cluster to Purple Heart - Southern France

Oak Leaf Cluster to Bronze Star - France

Silver Star for action in Bastogne

Presidential Unit Citation for action in Bastogne

Croix De Guerre - Belgium

Croix De Guerre - France

Seven Battle Start - ETO ribbon

American Theatre Ribbon

American Defense Ribbon

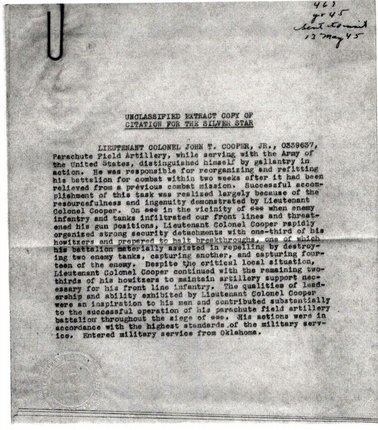

Silver Star

Unclassified Extract Copy of Citation for the Silver Star.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL JOHN T. COOPER, JR., 0339637, Parachute Field Artillery, while serving with the Army of the United States, distinguished himseld by gallantry in action. He was responsible for reorganizing and refitting his battalion for combat within two weeks after it had been relieved from a previous combat mission.

Succesful accomplishment of this task was realized largely because of the resourcefulness and ingenuity demonstrated bu Lieutenant-Colonel Cooper. On *** in the vicinity of *** when enemy infantry and tanks infiltrated our front lines and threatened his gun positions, Lieutenant-Colonel Cooper rapidly organized strong security detachments with one-third of his howitzers and prepared to halt breakthrough, one of which his battalion materialy assisted in repelling by destroying two enemy tanks, capturing another, and capturing fourteen of the enemy. Despite the critical local situation, Lieutenant-Colonel Cooper continued with the remaining two-thirds of his howitzers to maintain artillery support nescessary for his front line infantry. The qualities of leadership and ability exhibited by Lieutenant-Colonel Cooper were an inspration of his parachute field artillery batallion throughout the siege of ***. His actions were in accordance with the highest standards of the military service. Entered military service from Oklahoma.

Clippings

Recollections about Bastogne

written by LTC. John T. Cooper, Jr.

From a letter written to Steven Ambrose.

Mourmelon

The 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion arrived at Mourmelon on December 12, 1944, five days before the 101st Airborne Division headed for Bastogne. The battalion was to be attached with the 17th Airborne, which was to arrive on or about Christmas 1944. While at Mourmelon, the battalion was attached to the 101st.

This proud unit had taken part in the airborne invasion of Sicily, fought in key battles in Italy and participated in the airborne operation of August 15th in Southern France. They had also spent considerable time with the First Special Service Force in Italy. They were a well experienced and battle-tried combat force.

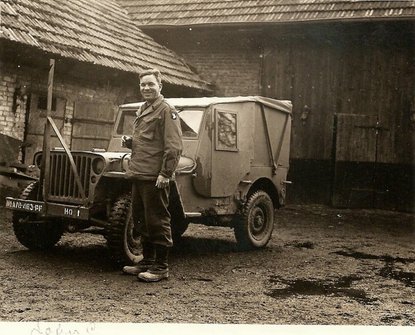

From November 18, in Nice, France, to the battalions arrival at Mourmelon, the 463rd was being refitted and rested. During most of its existence, save for the airborne drop in Southern France, the 463rd had been utilized as a ground equipped unit and had been provided with its own transportation. The battalion arrived with 27 ¼ ton trucks, two 1 ½ ton trucks, with a strength of 40 officers, and 553 enlisted men. The unit had also in inventory more than 200 anti-tank rounds, a factor of some significance just a few days hence.

The wartime commander of the 463rd PFA said his battalion felt like a lost and unwanted child when its men arrived at Mourmelon. He wrote the following:

Upon arrival I made a call on Division Headquarters and met General McAuliffe and Tom Sherburne, the Executive Officer to Gen. McAuliffe. To my surprise I found that Gen. Taylor, most of his staff and the battalion CO’s were either in the States, in England or in various parts of France on R&R. I was indeed fortunate to have been refitted before arriving in Mourmelon. I was invited by Col. Sherburne to take my officers to the F.A. Mess. That evening we met all the officers, not on leave, of the Field Artillery. For the next few days there was the usual chatter and talk. Most of the talk was of Normandy and Holland.

The staff of the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery consisted of myself, Lt. Col. John T. Cooper, Jr., Battalion commander; Battalion Executive officer and

S-1, Major Stuart M. Seaton; S-3, Major Victor E. Garrett; S-4, Capt John F. Keester. The Battery commanders were; A Btry, Capt. William H. Gerhold; B Btry, Capt. Ardelle E. Cole; C Btry, Capt. Roman W. Maire; D Btry, Capt. Victor J. Tofany. The Battalion surgeon was Capt. John S. Moore.

As you know the 101st had never heard of the 463rd Parachute F.A. Bn. and the members of the officers mess did not care to hear about “our” war, from which the 463rd emerged as battle hardened and proven outfit, because they had fought the only battles worth talking about.

In a crowd as large as large as the artillery officers mess it was impossible to talk at all, but during a little lull in the conversation at my table, the question of knocking out tanks arose and I said “My battalion has knocked out several German tanks in fights in Sicily and Italy, and that it was our experience that it was possible, with a 75mm howitzer, to “knock out” a German tank.” That was as far as I got that night as I was told by the other battalion commanders that General McAuliffe firmly believed that you could not knock out a tank with a 75 pack. You could disable one if you got lucky hit on a tank, but not knock one out. The conversation of Normandy and Holland so overshadowed the conversation that no further discussion of the 463rd’s tank busting got out during the meals at the mess. After this, as I met with the Officers of the 101st, I was greeted with the refrain, “how many tanks have you knocked out today, Cooper!”

During this five day period our mail finally caught up with the unit and I spent some time trying to get the 101st ordinance supply group to fill out some remaining request for material and parts the battalion needed to top out its T.O. & E. The list wasn’t large but I kept getting denied by the 323rd Ordinance Battalion which was stationed a short distance from Mourmelon. The reason given were short supply and that the requisitioned parts were on back order. Sensing a stone wall I returned to the unit CP to read my mail. I had received several letters from my wife, Alice, in Oklahoma, one of which informed me that my brother-in-law, Sgt. Ed Vaughan was stationed with the very same ordinance unit, the 323rd which I had been requisitioning earlier. What luck ! It had to be fate, one of those incidents right before a momentous occasion that if not for the letter, the events of the next week may not have had the same outcome. I instantly ordered my jeep and returned to the supply group and found my brother-in-law and with Ed’s pull, finally topped out the 463rd’s T.O. & E. I now had a fully staffed, trained and supplied F.A. battalion. I still believe that without Ed’s help, my battalion would not have had the distinguished results we had at Bastogne.

A few days later, sometime during the day of the 17th of December, we got the call to meet at Division HQ. Upon arrival I found a seat with the other artillery battalion C.O.’s and listened to the General explain about the German breakthrough some 200 miles northeast of our location and that the 101st would get cracking and go to Werbomont, Belgium. It was a somewhat lengthy meeting and many questions about the size and strength of the German offensive, personnel recalls, troop movements and transportation and ordinance issues were discussed and some decisions were arrived at.

There was a long discussion on how many trucks it would take to move a company, an HQ company, a battalion, etc…

An artillery battalion C.O., Carmichael[1] asked ‘how much ammo to take’. The staff after due consideration came up with the answer ‘A basic load’. If anyone had looked up the basic load for a Parachute 75 Pack, they would have found that 100 rounds made a basic load, hardly enough to register a Battalion’s guns. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing ! For air drops, yes, but not when moving by truck. In my experience with the 463rd in Sicily and Italy, we packed as many rounds of ammo we could carry, regardless !

There was not an officer in the room, including all the infantry colonels, their staffs or any of the staff of General Taylor, that had the past experience of moving an outfit, company or battalion by truck over any distance, with the necessary troops, equipment, ammo and communications, ready to go into a major engagement as soon as they arrived.

After the meeting broke up I went in for a private talk with Colonel Sherburne and General McAuliffe. In the hustle and bustle of getting ready to go, the General had forgotten about my battalion and that we were attached only for supply and administration. We were to be assigned to an airborne unit that was scheduled to arrive any day. But ‘I wish I could take you, as the 327th needs a direct support battalion’, he asked me how many trucks I would need to make the trip. I told him that I would not need any trucks for the move, but we would need all we could get to haul ammunition.

I left that meeting very much disturbed about the apparent disorganization of the total show. With the understanding that if I chose to go, they would be glad to have me, but I would have to talk to Bud Harper [2]and work out a deal with him.

I went back to my unit and asked the EXO, Major Seaton, to call an officers meeting, all officers. I explained to them what had happened and that we could stay in Mourmelon or go with the 101st to Werbomont. If we go to Werbomont with the 101st we will have to support a Glider Regiment.

This sounds silly as hell, but we had jumped into Sicily with Col. Jim Gavin’s regiment and the 82nd Airborne Division. Later, when the 82nd went to England, we were detached (456th Parachute Field Artillery) to stay and support General Frederick and the First Special Service Force through the Italian Campaign to the capture of Rome on June 6th 1944, and later combat-teamed with the 509th Battalion for the Southern France campaign up to the French Alps prior to moving from the front line in Southern France to Mourmelon. We had all of the parachute bravado and disdain for the glider troops.

Needless to say, our discussion at that meeting of officers lasted as long as General McAuliffe’s and we discussed only one thing. Shall we go and support a damn glider outfit or stay in Camp Mourmelon. (As it turned out the damn glider outfit, the 327th Infantry, turned out to be one of the best units that we served with during the entire war. ) Holding the whip hand, I finally told my officers “that the choice they had was to stay in Camp, shave every day, stand retreat, and be officer of the day. Furnish the camp guard, make up and follow a strict training schedule daily. Spit and polish all the way or go and support the 327th.”

I gave the officers this decision since, if we went, the 463rd would technically be AWOL. With the information on the table, Major Seaton and staff arranged the order of march, and the battalion was loaded and ready to move the next morning before the trucks began to arrive for the rest of the division. Some of our trucks were not unloaded from the trip up from Southern France. Unlike quite a few units heading for the Ardennes, the 463rd had been fully supplied with our wool overcoats and “mud” pack overshoes in the French Alps prior to reassignment in Mourmelon.

Off to Bastogne

The day passed agonizingly slow as I waited for Harper to return from England. All we could do was watch as the 101st scurried about loading their trucks and begin to move out.

Around 2100 hrs. December 18, 1944, I finally found Colonel Harper who just drove up. The 327th was the last regiment out. I talked to Colonel Harper about two minutes. He spoke briefly, ‘Hell yes, I can use a battalion. Just follow the regiment out.’ That was at 2130….

My jeep was number 1 in my column. As we passed the ammo dump I turned and took the whole battalion through with orders to load as much 75mm ammo as we could carry in any vehicle, regardless of how crowded they were.

This turned out to be the smartest hunch I ever made. After arriving in position at Hemroulle the second day we were asked for an ammo report. Soon after the report I was called to verify the report, and after verifying the total amount of ammo, I was told that we were designated the ammo dump for the Division and would abide by the allotment to be furnished by Division daily. So much for the basic load. Our battalion had been trained for the past year and a half that anytime the gun was less than 500 rounds, order another load to be brought up.

The column crossed the Meuse early in the morning of the 19th with frequent stops and delays, then we entered Belgium. Near Bois de Herbaimont, where the northward route intersects the Namur-Bastogne road, the convoy turned southeast towards Bastogne.

The morning seemed gray, dreary and wet. It was cold. As the convoy made its stops and starts, men would use the delays to pour gasoline in shallow holes in the road and lite it to try and stay warm. Some tried to heat beans or try to make coffee over flaming cans of C-ration partially filled with gasoline soaked gravel. Along the way we passed soldiers of the 28th Division going the opposite direction. They looked haggard, tired, and old. We knew we were in for a long fight. I could hear some of my men yell at the 28th, “Hey, you are going the wrong way”, but their voices weren’t full of the usual bravado.

Hemroulle

When we arrived at the crossroad to Bastogne about 0900 hrs. the morning of the 19th, to my surprise, Col. Sherburne was in the middle of the road directing traffic. He told me to go on toward Bastogne and pull off the road some place and wait for orders. We went on down the road and pulled off in an assembly area near Flamizoulle. The day had cleared, just right for an air attack, but it never came. We looked at the map and I picked out a town by the name of Hemroulle. I ordered Major Seaton and Garrett to take the unit on to Hemroulle and begin to dig in. I left in search of Sherburne’s staff to tell them that I would make this town my HQ., put my guns in positions and be ready anytime after an hour and asked them to lay a line to my HQ.

I found the house where Division Artillery was supposed to set up. I went in and asked about the situation and when we could go into position. I was told that they (Div. HQ. staff) didn’t know but if I wanted to go into position, just pick one out and get ready, that it would be good training. The Staff was just waiting for further orders.

While at HQ’s I found out that there was no wire, as of yet, at the Division fire direction center, nor was the switchboard ready for incoming wire from the Battalions. Communications told me that as soon as wire was found, they would lay the line immediately.

At about 1500 hrs. I returned to the 463rd’s CP and found that the staff had done their usual exceptional job in setting up and that my HQ Battery CO, Capt. Aurby Milne, had already laid a line to Division Artillery and tied it to a tree and put a telephone on it. I called Division and told the people in the HQ to call me if anything developed. For the first few hours Capt. Milne, his assistant, 1st Lt. Melvin A. Dewar and their HQ’s battery laid lines to all Artillery Bn’s, as they were located. For the first days of battle in and around Bastogne, the 463rd served as the Division’s fire direction center.

Early evening of the 19th of December, in Hemroulle, Division Artillery called for an ammo report. I don’t remember the exact number of rounds or the type but it had to be over 5000 rounds, because we fired over 2000 by the 23rd before resupply by air late on the 23rd. I ordered daily trips back to the ammo dump which was back toward Mourmelon and past Neufchateau, Belgium.

Only one truck made it back before the Germans isolated us by cutting the road to Neufchateau on the morning of the 20th December, 1944. This truck was driven by our Greek compatriot, Pvt. Saxiones. Saxiones was stopped three times while returning with his truck load of 75 pack ammo by advanced troops of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. Since Saxiones spoke fluent Greek the Germans must have thought he was delivering ammo for their troops and passed him through… I’ll never forget how frustrated Saxiones was when I was called to the MP check point, along the perimeter of the Bastogne area on the Neufchateau road. Our MP’s had detained Saxiones thinking he was stealing ammo for the Germans because they couldn’t understand 463rd in broken English and Greek… That man deserves a medal for that day’s work.

As we got better organized and battalion officers met at Div. Artillery, I was again greeted with “How many tanks you knocked out today Cooper?” Needless to say, this was getting under my skin, but I just laughed and said, “wait a day or so until the Germans get brave enough to break through the Infantry.” Sometimes you don’t mean what you say…

The Christmas Day Attack

The days prior to Christmas began to pass about like all the others we had been in for the past year. Each day presented its targets and we fired our missions. From these positions we fired 6400 mills. As it began to snow and ammo decreased to critical conditions, we organized our battalion for the possibility of stand and fight, for there were no other places to go. We posted, dug in out-post guards with telephone communications to battalion HQ as well as to the battery they represented. Guns covering all tank approaches were dug in and prepared. Our guns were mutually supporting. Banking on the fact that a tank will attack a gun head-on, we had another gun that would have a side shot at the tank. This was the experience we had developed in Sicily and Italy and was now ready to be used on the Germans in the Ardennes.

We had 20 rounds per gun of hollow charge anti-tank ammo that were never to be used or counted in ammo reports except to be used for direct fire. The preparation for the tank attacks we received on Christmas Day had been planned and set up for several days. Snow had covered the gun positions. All we had to do was move our gun section in and start shooting.

Now this sounds like a lot of thought had gone into this, and one is correct, but the thinking and training that executed this plan was practiced, but never used before. We practiced it and did the same thing on Anzio Beach Head and every time we changed positions coming up through Italy. We knocked out our tanks in Sicily before we were sharp enough or experienced enough to have a plan. After Sicily and before Italy, we had faced tanks unprepared, knocked out two, lost several men and officers. After the tank attack in Sicily, witnessed by Colonel Gavin, he said “give every man in that crew the Silver Star”. We collected more Silver Stars in Sicily than the Infantry. All of the preparation for what was to happen on Christmas was made routinely, it just came together on Christmas Day.

Now it was early on Christmas morning : I was awakened before down by my S-3, Victor Earl Garrett from the operations room across the hall in the house we were using for our CP. He told me that eleven tanks had moved in on Sgt. Booger Childress’ “B” Btry. Some four tanks had stopped so close to him that he might be discovered if the soldiers moved around very much. He could hear the other tankers and they had gotten out of the tanks and were waiting around, preparing coffee for the morning breakfast. He had to whisper. Snow was about a foot deep all over the place.

I told S-3 to alert all the batteries and for them to stay in their sacks, except for the C.O. and executive officer and gun crews. Movement in batteries are to be kept at a minimum. No lights. No one was to fire a round until we gave the order ‘Let the shit hit the fan!’

This obscene bit of literature happened to be here because of a story that had recently been told to me by a man in my unit who occupied a room above the bar in my CP and overheard the order while relieving himself through a knothole in the floor. I wish I could remember that man’s name. Later after the Bastogne breakthrough by Patton’s units, in a conversation somebody said, “where were you when the shit hit the fan ?” It was adopted as the Battalion’s inside joke. It showed that we were still gung-ho and didn’t give a damn, just like a paratrooper! But that’s the way it happened.

As it was still dark and as the word got out, our gunners had occupied their gun pits and other outposts were able to see the tanks, we had a good view of what we had to do.

You will remember how I was greeted for several days by ‘how many tanks did you knock out today ?’

I was now determined to be able to give Elkins[3] and Carmichael a damn good answer. I was also sure that Patton’s tanks were in the vicinity and I was damn sure we were going to shoot German tanks. I told the S-3 that we would not should until we could see the muzzle brakes on the guns or the Swastika painted on the tank. I wish to call your attention to the fact that these eleven tanks were not painted white and were not part of the tank group that came through and hit the 327th and 502nd at Champs.

I must call to your attention that my Bn. had come through Sicily, Italy, and through Southern France to the Maritime Alps. We had fought through the roughest terrain in all kinds of weather. We had collected our trucks, 50 caliber machine guns, bazookas and anything else we thought of or through experience taught us the need for, I added to the Battalions T.O.&E. Not being attached to a Division, any Army or Air Corp aided us in this matter. I had organized this Battalion with a provisional T.O.&E. (typed) to include the above. I had more trucks, jeeps and ¾ tons than the entire Division, and had more officers and men trained in the use of 50 calibers, bazookas, than any artillery parachute battalion, and over the past 166 days prior to joining the 101st Division, had fired more than 120,000 rounds of ammo.

So, the Germans got out of their tanks and made coffee and sat around waiting for daylight. They did not know that while this was going on, they were being observed through the tube of a 75 pack howitzer, which would soon be loaded with 75 hollow charge ammo, probably the only such ammo in the (European) theater and they had parked in front of the only gun that had the ammo. As the Germans began to make a move, we could see the muzzle brake on the guns. The S-3 gave the order, ‘Let the shit hit the fan’

I picked up my telephone to Division and reported the attack on the 463rd. We would like some help but would stay in contact and not give ground. Our HQ was being attacked.

‘Cooper, are you making this up?’ someone asked at Division. ‘Hell no, look out your window and you will see five smoke columns, each a burning tank. No, make it six, there goes another one. ‘

‘We will get T.F. Cherry down as soon as possible, out.’ Division Artillery replied.

In the first 15 minutes we had disabled 8 tanks, hit 10 tanks, the one close to Childress on the turret, killed two on the inside and one getting in. Childress called and said he had dragged the men off the tank and got the two dead men out. I told him to sit tight, but put a white undershirt on the tube and wait for me. By this time, about 45 minutes had passed. Walter Sckerl, my driver, and I drove out and led the tank, driven by Booger, down a draw into our HQ area and parked it outside my HQ.

Soon after the show was over, General McAuliffe, Col. Sherburne, Elkins and Carmichael and a host of observers came in the area and the General went out to check the area. McAuliffe would approach a burning hulk of a tank and say, ‘What gun hit this one?’. It so happened that two tanks were hit in the side and were burned out. There was a streak in the snow that went directly to a gun aimed on those two. ‘I’ll give you credit for these two and the one you captured, but this other cannot positively be identified as being knocked out by your guns.’ While we were there in the field, I asked the General if ‘these tanks were disabled or knocked out ?’ He replied, ‘anytime a tank is hit and burns up, it is destroyed and knocked out.’ I asked if I could use the phrase in the after action report. ‘Hell yes!’

I turned to Elkins and the rest of the General’s group and said ‘I got my tanks today!’ I felt good all over.

Col. Sherburne made a written commendation in which he gave our unit credit for 2 tanks and the capture of one.

Afterthought

The tank fight Christmas morning was just another day of many days. Some or most of the days were not as momentous as December 25, 1944. I had no gut instinct nor expected anything special for that day. We all did what we had to do when circumstance placed us in harm’s way.

If I had ever thought that we would be remembered for what was happening that morning, I would have asked the General while we were on the field that morning, “who else other than the 463rd had bazookas or artillery, who else had 50 caliber guns, who else captured these Germans”. Now I ask, “has anyone else in the 101st ever claimed to have knocked out any of our eleven tanks ? We lost two and were told that Cherry got one of them when he came to our aid. No American anti-tank guns and or tanks were involved in this fire fight.

[1] 321st Glider Field Artillery

[2] 327th Glider Field Artillery

[3] 377th Parachute Field Artillery