Articles and Magazines

World War II Magazine

This article was written by Martin F. Graham and originally appeared in the December 2004 issue of World War II.

World War II has given authorization to our 463rd PFA site to publish the article. Many thanks to the magazine and to Martin !

HIGH TIDE AT BASTOGNE

In stopping the last major German assault against Bastogne, the veteran gunners of the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion proved their skill to skeptical troops of the 101st Airborne Division.

By Martin F. Graham

Sergeant Joseph Rogan took a long drag from a cigarette as he stared intently at the terrain that disappeared into the darkness and fog to his front. It was about 3:30 a.m. on December 25, 1944, and Rogan was spending his second Christmas overseas in a foxhole on the outskirts of Bastogne, Belgium.

His partner, Corporal Restor Bryan, was resting in the corner of the hole, enjoying a rare moment when he could sleep in this intensely cold, snow-covered region. Rogan and Bryan were forward observers for the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion.

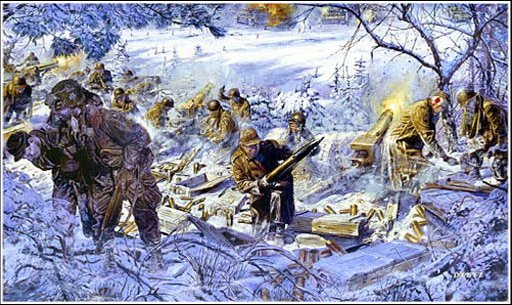

Jim Dietz's Stopped Cold depicts the high-water moment of German efforts to break through American lines around Bastogne. Early on Christmas morning 1944, the Germans threw 18 tanks and supporting infantry against the lines of the 401st Glider Infantry Regiment and the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion.

The sound of distant shells and bombs crashing around Champs did not even stir the exhausted infantry and artillerymen, leaving Rogan alone to think about home and happier Christmases. The 594 men of his artillery battalion should have been sleeping off their hangovers from Christmas Eve celebrations in Mourmelon, France. They had arrived there only 13 days earlier with orders to join the 17th Airborne Division once it came in from England. Instead, the holiday found them battling German tanks and troops desperately attempting to pierce the American defenses around Bastogne.

Never willing to dodge a fight, the 463rd's commander, Lt. Col. John Cooper, had volunteered his unit to Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, the 101st Airborne Division's acting commander, as soon as he heard the division was being rushed to Belgium to help repel a major enemy breakthrough. Cooper's zeal was a lucky break for the men of the 101st. The veterans of the 463rd had already distinguished themselves in combat in Sicily, Italy and southern France.

The 463rd's odyssey to this Christmas morning in Belgium began in February 1942, when the War Department authorized the creation of the first test parachute artillery battery. That experimental unit would become Battery B, 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. Colonel Harrison B. Harden Jr. was designated the new battalion commander. The battalion's first combat jump was in Sicily on the evening of July 9, 1943, in support of the 82nd Airborne Division's 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

The battalion's primary mission was to fire at enemy troops and tanks utilizing a high arc, or indirect fire. During the intense Battle of Biazza Ridge, however, the battery had scored its first victory against enemy tanks using direct fire. Following the Sicilian campaign, the battalion was split up. Batteries C and D remained with the 82nd Airborne Division and transferred to England to prepare for the invasion of France. Headquarters Battery and Batteries A and B supported the 1st Special Service Force and participated in the Italian campaign battles for Monte Cassino, Anzio and Rome. In February 1944 the three batteries were redesignated the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, with Major Hugh A. Neal as battalion commander. Neal's command was short-lived, however, for less than four months later an enemy shell seriously wounded him. He was replaced by Cooper, who remained the battalion commander for the duration of the war.

In early July, the 463rd received 200 replacements, which were used to create Batteries C and D. Now a complete battalion once again, the 463rd was attached to the 1st Airborne Task Force and jumped into southern France on August 15. By the end of the month, the 463rd was transferred to the French Maritime Alps to assist in blocking any attempted German escape from France into Italy. At the beginning of December the battalion was transferred to Mourmelon, where it arrived on December 12. By then, a large number of the 463rd's members had been overseas more than 19 months.

The battalion was ordered to rest and refit while waiting for the 17th Airborne Division, then in training in England. As it awaited the arrival of its new division, the battalion was temporarily attached to the 101st Airborne Division for administration and rations.

A few of the artillery battalion commanders in the 101st, unfamiliar with the 463rd, thought the battalion consisted of a bunch of greenhorns just arriving from the States. During one dinner discussion between Cooper and officers from the 101st, a debate developed about the ability of a 75mm pack howitzer to knock out a German tank. At one point, Cooper said, "We certainly can knock out Mark IV tanks with a 75 pack howitzer." An artillery officer from the 101st responded, "Do not ever say, in your after-action reports, that you knocked out a tank, because General Anthony McAuliffe says you might disable, but you'll never knock out a tank." Incredulous, Cooper was quick to respond to the taunt. "We have spent more time waiting for our parachutes to open," he said, "than you guys have spent in combat since the invasion of Europe." Cooper would soon have an opportunity to back up his words with deeds.

Fate had placed Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, the 101st's artillery commander, in acting command of the division when word reached Mourmelon that the Germans had launched a major offensive in Belgium. Major General Maxwell Taylor, the 101st's commander, was in the United States, and his deputy, Brig. Gen. Gerald Higgins, was in England along with five senior divisional commanders and 16 junior officers to discuss the recently concluded operation in the Netherlands.

After being alerted by XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters, McAuliffe called a division staff meeting at 9 p.m. on December 17 to mobilize the division.

To his shocked and sullen officers he announced, "All I know of the situation is that there has been a breakthrough, and we have got to get up there." He informed them that they should be ready to move out by truck the next morning for Werbomont, Belgium.

As the meeting broke up, Cooper approached McAuliffe and the acting division artillery commander, Colonel Thomas Sherburne, to remind them that his unit was only temporarily attached to the 101st and requested permission to join the division in its advance.

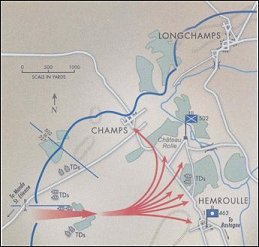

Left :

When German tanks broke through the lines of the 401st Glider Infantry Regiment and approached Hemroulle, their elated crews reported that they had reached the outskirts of Bastogne.

McAuliffe directed Cooper to talk to Colonel Joseph H. "Bud" Harper of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, which lacked direct support artillery. Cooper found Harper, who had just made it back from England, and asked, "Do you need me?" Harper replied, "You're goddamn right." As a formality, Cooper returned to his battalion and gave his officers a choice of whether to stay and wait for the 17th or to join the 327th. To a man, the officers voted to go.

The division's convoy began leaving Mourmelon at 9 the next morning. Since the 463rd would be supporting the 327th, which was the last infantry regiment to leave, Cooper's battalion did not set out until 9:30 that evening. After more than a year of active campaigning Cooper knew that you could never have enough ammunition and directed the battalion's truck drivers to pass by Mourmelon's ammunition dump yard.

"As we passed the ammo dump," Cooper remembered, "I turned and took the whole battalion through with orders to load as much 75mm ammo as we could carry in any vehicle, regardless of how crowded they were." This extra ammunition would come in very handy a few days later when the Germans cut all supply lines into Bastogne.

By the time the 463rd entered Belgium, the division's destination had changed from Werbomont to Bastogne. The 327th was directed to cover a position to the west of the town. Cooper's command deployed its guns around the small village of Hemroulle, about a mile northwest of Bastogne. The command post and fire direction center were set up in a house across the street from the village church, which was designated as the battalion aid station. While the primary mission of the 463rd was to support the thinly covered western and southern sector held by the 327th, it was called on daily to assist in repelling the Germans from the other sectors of the 101st's perimeter.

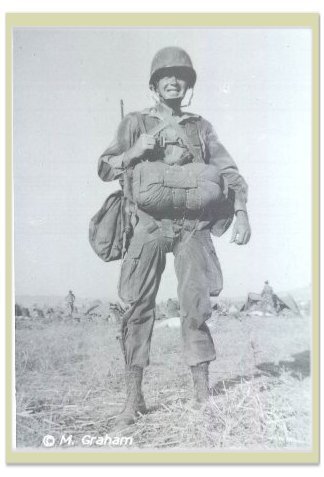

Right:

Battery B, 463rd Parachute Field Artillery, gathers in the warmth of a sunny Italian day for a unit photograph prior to their drop into France in August 1944. Four months later, these experienced paratroopers would be enduring the coldest European winter on record.

On the 19th, the Germans cut off the 463rd supply train, which Cooper had sent back for more ammunition. The next day, they succeeded in blocking all roads into Bastogne and launched major assaults on the 101st's positions northeast and east of the town.

Even with the extra ammunition they had brought with them, by the 22nd--after supporting efforts to repulse earlier German attacks--the battalion had little more than one day's worth of rations and ammunition left.

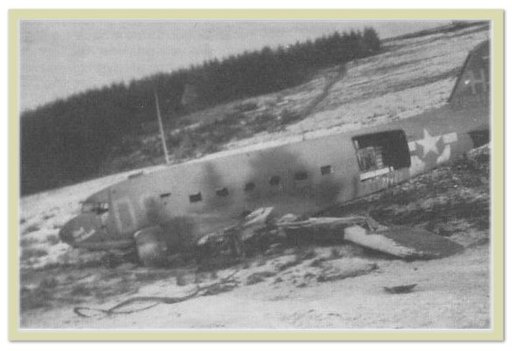

The temperature on the morning of the 23rd was 10 degrees above zero, and it remained painfully cold throughout the day. Despite the freezing temperatures, the men's morale improved somewhat when they looked up around noon to see the sky filled with red, yellow and blue parachutes dropped by 16 Douglas C-47s. It was an early Christmas for the "Battered Bastards of Bastogne." One of the planes was shot down by enemy fire and crash-landed near the 463rd's position.

Every morning during the siege the division's artillery commanders would gather to discuss their situation and to prepare for the day ahead. Remembering Cooper's earlier boast about his battery's effectiveness against enemy tanks, at every one of the meetings either Lt. Col. Edward Carmichael, the commander of the 321st Glider Field Artillery Battalion, or the commander of the 377th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, Lt. Col. Harry Elkins, would ask, "Cooper, have you knocked any tanks out yet?" His answer was always, "No, not yet." That was about to change.

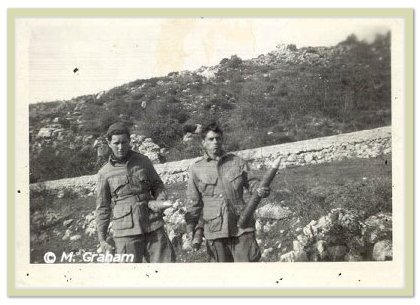

Left:

Lieutenant Colonel Edward Carmichael (left), the commander of the 321st Glider Field Artillery Battalion, relaxes with Lt. Col. John Cooper, commander of the 463rd. During the siege, Carmichael repeatedly asked Cooper if he had knocked out any panzers yet.

The 24th was clear and bright although still very cold. Another 160 planes dropped an additional 100 tons of supplies. Foragers from the 463rd found flour, sugar, lard and salt that had been left by the VIII Corps when it hastily departed Bastogne at the start of the German offensive. Even though they were surrounded, the morale of the men remained high. By the afternoon of the 24th, division headquarters was convinced that an attack was likely in the 327th's sector either that day or the next. For the past week, German troops and tanks had tried to puncture holes in the 101st's defenses east and south of Bastogne. Troop deployment to defend against these attacks had weakened defenses west and north of the city. Almost half of the 101st's line was now covered by the 327th.

On Christmas Eve, the 101st's operations officer, Lt. Col. Harry W. O. Kinnard, had regrouped the defenders around the perimeter of Bastogne, a line almost 16 miles long. Kinnard attached the 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion, two platoons of the 9th Armored Engineer Battalion and four platoons of the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion to the 327th along with an amalgam of infantry, tank destroyers and tanks. Sergeant Rogan knew little of divisional intelligence estimates, but he could hear the sound of armored vehicles being deployed in his front as the sun went down on Christmas Eve. Unknown to him and the others huddled nearby in their foxholes, these tanks and their supporting infantry were making final preparations to come crashing through their lines early the next morning.

Rogan, Bryan and Everhardt were acting as forward observers in support of the men of the 1st Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry Regiment, which was serving as the 327th's third battalion. Nearest to the three artillerymen were the 77 men of the 401st's Company A, commanded by 1st Lt. Howard Bowles. The lieutenant's men defended a large section of the flat, frozen plain west of Hemroulle. They were deployed across a 1,200-yard front line along a ridge about 25 feet high. There were two small woods on top of the ridge about 50 yards apart, with an open field between them. One of the woods concealed two tank destroyers. Two more tank destroyers were in a group of trees some 400 yards to the left of Company A's position. Company B of the 401st was dug in on the right side of Company A on the ridge, extending about 1,100 yards to a roadblock on the Champs to Mande St. Etienne road. The troops were also armed with machine guns and supported by four tank destroyers. The battalion's Company C was kept in reserve near the 463rd's command post at Hemroulle.

Anticipating an attack along his front, Cooper positioned outpost guards with telephone communications to battalion headquarters and battery commanders. He deployed the antitank guns in mutually supporting positions. Experience had taught him that a tank will attack a gun head-on, so he had another gun that would have a side shot at any approaching tank. Each of Cooper's guns had 20 rounds of hollow charge antitank ammo to provide direct fire against enemy armor. At about 3:30 a.m., Rogan radioed his battalion's operations officer, Major Victor Garrett, that he and his supporting company had been overrun by an enemy tank column accompanied by white-capped infantrymen, some riding on the back of the panzers. He informed Garrett that the tanks were moving toward Hemroulle.

Rogan had seen 18 whitewashed Mark IV tanks belonging to the 115th Panzergrenadier Regiment of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division move through his position and pass between the two wood lots. The column was accompanied by two battalions of the 77th Panzergrenadier Regiment. Each tank had 15 or 16 infantrymen, wearing white sheets, riding on it while others walked beside the tanks. As the Germans crossed Rogan's position, they fired rifles and flamethrowers, probing and trying to identify the American frontline positions. When they pierced Company A's line, the Germans killed four Americans, including Rogan's companion Restor Bryan, and wounded five. Allowing the tanks to pass, the survivors re-emerged from their holes and prepared to do battle with the infantry that was following behind the tanks.

Above: Snapshots of the 463rd taken during the the fighting at Bastogne.

The trooper on the upper picture has been lucky enough to obtain a mountain troop parka in Italy.

After driving through what he believed was the weakly held American front line, at 4:15 a.m. the German tank commander radioed headquarters that his advance was proceeding successfully. He reported that the only evidence of American resistance were pockets of enemy infantry and tank destroyer fire. A half-hour later he informed his superiors that his panzers had reached the western edge of Bastogne. German headquarters was elated, but the celebration was short lived. Word of continued progress toward that long-sought objective never came; instead, German forward observers reported hearing the crash of artillery fire and mortars from the direction of Hemroulle.

The 18 Mark IVs and their accompanying grenadiers had actually only advanced to the outskirts of Hemroulle, mistaking it for Bastogne. As they approached the road between Hemroulle and Champs, the German armored force split up. Seven of the tanks headed in the direction of Champs, while the others moved to a ridge overlooking Hemroulle and parked.

Shortly after receiving reports of the enemy attack, Garrett woke Cooper with the information that German tanks had pulled off the road near one of the 463rd's outposts. The panzers had assembled behind a line of trees on a ridge overlooking Hemroulle. Garrett informed Cooper that the enemy tank crews had dismounted and appeared to be preparing breakfast. The artillerymen counted 11 tanks and a large number of German soldiers, including all of the tank crews.

Since it was too dark to positively confirm that these were truly enemy tanks, Garrett told his men to sit tight until they could see either the muzzle brakes on the tanks' guns or the crosses painted on the side. Cooper knew that American armor was on the way to relieve Bastogne and did not want to pour fire on friendly tank crews.

The panzers were directly in front of three of the 75mm guns deployed in antitank positions, about 500 to 600 yards away.

Cabbott Boothe, one of the men of the 463rd who later fought at Bastogne, poses prior to the jump into southern France.

When they were first attached to the 101st, Cooper's veteran troopers were mistakenly treated as greenhorns by the "Screaming Eagle" artillerymen with whom they shared quarters.

Above left: Braving intense anti-aircraft fire, the pilots and crews of Douglas

C-47s dropped critically needed supplies to Bastogne's defenders.

This plane came down near the 463rd's lines.

Right: Martin Graham, the author's father, was a member of Battery B.

Garrett directed the gun commanders to quietly bore sight their guns on the tanks and prepare to fire as soon as they could confirm that these were indeed the enemy. Cooper's plan was to have one of the three guns shoot the first tank in the line while the other two went after the remainder. All the battery's other guns would then fire at will. Garrett spoke with the commanders of the other guns, directing them to remain quiet and not begin firing until he gave the order, "Let the shit hit the fan."

Once the tanks began to move, the artillerymen could make out the muzzle breaks on the guns, and Garrett ordered, "Let the shit hit the fan." Cooper later remarked that with those words, all hell broke loose. Several tanks were immediately disabled by the 463rd's guns, their crews scurrying from the turrets of the burning panzers.

The artillery was quickly joined by soldiers from Batteries A, B and C with bazookas, machine guns and rifles firing at the tanks and the enemy infantry around them. Since most of men of the 401st were busy with the infantry that had followed the tanks on foot, Cooper's men were part of the thin buffer blocking the German armor and infantry from the center of Bastogne, less than a mile away.

As soon as the fighting began, Cooper called division headquarters and informed them that the 463rd had been attacked and would hold out as long as possible. To the question "Cooper, are you telling me the facts, that you are under attack?" Cooper replied, "If you don't believe it, look down this way, and you will see five spirals of smoke, which represents five tanks burning--no, there are six spirals of smoke, which makes six tanks burning."

Cooper did not know how long his battalion could hold out, but he was determined that his guns would slow the enemy advance, if not stop it. By 8:30 a.m. enemy infantry had approached to within 200 yards of the 463rd's command post in Hemroulle. Cooper ordered all classified documents and the M-209 cryptographic machine destroyed. Captain Victor Tofany of Battery D and the other battery commanders ordered their men to stack their barrack bags in a pile, ready to be burned if the enemy broke through.

There was no need. The fight in and around Hemroulle ended at about 9 a.m. with the destruction of the last of the German tanks that had attacked the town. The seven panzers that had veered away from the column heading toward Champs met the same fate. Although panzers knocked out two tank destroyers from the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion, they were themselves destroyed by a combination of fire from American tank destroyers and bazookas fired by members of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment near Champs.

Left: With snow swirling around him, Battery A's Ike Isasky stands behind one of his unit's .50-caliber machine guns.

Right: Three members of the 463rd during warmer times in southern France.

While his battalion fought the tanks outside of Hemroulle, Rogan had been with the remaining men from the 401st as they shut the door behind the tanks and dealt with their supporting infantry. Brought out of reserve, C Company of the 401st joined the fight against the 115th until daybreak, when American artillery and mortars could deal with the enemy infantry, which was now outlined against the snow-covered slopes west of Hemroulle. Battered by increasingly accurate American artillery fire and the small arms of the 401st, the Germans tried to dig in and hold what they had gained, but the ground was frozen. Instead, they hugged the earth and waited for the artillery to stop. During a brief lull their commander, Colonel Wolfgang Maucke, had his men retreat to a hill southeast of Flamizoulle. Allied aircraft soon began battering Maucke's isolated men. By nightfall it became clear that the German force that attacked early on Christmas morning had been almost completely destroyed, with the bulk of the men dead, wounded or captured.

While his battalion fought the tanks outside of Hemroulle, Rogan had been with the remaining men from the 401st as they shut the door behind the tanks and dealt with their supporting infantry. Brought out of reserve, C Company of the 401st joined the fight against the 115th until daybreak, when American artillery and mortars could deal with the enemy infantry, which was now outlined against the snow-covered slopes west of Hemroulle. Battered by increasingly accurate American artillery fire and the small arms of the 401st, the Germans tried to dig in and hold what they had gained, but the ground was frozen. Instead, they hugged the earth and waited for the artillery to stop. During a brief lull their commander, Colonel Wolfgang Maucke, had his men retreat to a hill southeast of Flamizoulle. Allied aircraft soon began battering Maucke's isolated men. By nightfall it became clear that the German force that attacked early on Christmas morning had been almost completely destroyed, with the bulk of the men dead, wounded or captured.

Soon after the fighting ended, Carson "Booger" Childress, a member of Battery B, radioed Cooper to tell him that he had captured one of the tanks in good running order. Childress informed Cooper that when the firing started, the tank crew had tried to get into the panzer, but it was hit on the turret, killing the first man trying to enter. The rest of the tank crew members ran for cover and were later captured by the 463rd's tank stalking party, commanded by Lieutenant Ross Scott. Cooper drove out to the tank and placed a white undershirt on the tube to identify it as captured. Ever the resourceful soldier, Childress figured out how to drive the Mark IV and followed Cooper back to his headquarters. The lieutenant colonel then called Colonel Sherburne, the acting division artillery commander, and told him that he had a Christmas present for him but that he would have to personally come to pick it up.

McAuliffe, Sherburne and a few commanders of other artillery battalions later arrived to view the scene of the Christmas Day battle.

Gunners Bradshaw (left) and Menchaca stand proudly beside a Panzerkampfwagen Mark IV destroyed during the Christmas Day battle.

Another one of the destroyed German tanks. This one was wrecked by a round fired at point-blank range from one of Battery A's guns.

As they approached the wreck of each tank, McAuliffe asked, "Which gun knocked this out?" They could clearly see ricochet marks across the snow in front of two tanks and could see the gun from which the shot was fired. McAuliffe stated, "I give you credit for these two tanks."

Cooper asked him whether these tanks were knocked out or disabled. He replied, "They're damn sure destroyed and knocked out." Cooper then turned to those present, including some of the officers who had been chiding him about the ineffectiveness of pack howitzers, informing them that his battalion had knocked out and destroyed at least two tanks with direct fire. The remaining tanks had been fired on from so many directions that McAuliffe and Sherburne felt it was not possible to confirm which weapon disabled them. Even though there had been other American tanks and antitank units in the vicinity, Cooper was convinced that since his guns had all 11 panzers in their sights, they had been responsible for the destruction of the entire force moving against Hemroulle. But as some of the tanks had moved after being struck, there was no way to confirm the kills. All that could be certain by the end of the day was that 18 panzers had attacked early on Christmas morning, and by 9 a.m., all had been destroyed, disabled or captured.

When Sherburne returned to his headquarters, he prepared his after-action report with a written commendation for the 463rd. Since it was impossible to prove that his battalion had destroyed more than two tanks, Stuart Seaton, the executive officer, and Cooper decided that in their report they would claim to have knocked out two panzers and captured one. Cooper did not want to begin a controversy with Sherburne by insisting that his battalion had actually knocked out eight tanks and captured one. Years later Cooper stated, "It is immaterial to me now what anybody thinks, but the battle Christmas morning at Hemroulle was strictly a 463rd encounter." Cooper and Rogan both received Silver Stars for gallantry in the action that Christmas morning. Bryan was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star.

Right : Stuart Seaton, the battalion's executive officer, later wrote the unit's after-action report, describing how the last great German effort to enter Bastogne had been defeated.

The next day, December 26, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.'s 4th Armored Division broke through the German ring around Bastogne. The 463rd remained in Hemroulle providing support fire around the perimeter of Bastogne until January 15, 1945, when it joined the 101st in its final push into Germany. On January 31, Cooper received orders to transfer his command to the 17th Airborne Division, the unit his battalion was originally designated to join. General Maxwell Taylor, however, intervened by stating, "The 463rd is firmly united with this [the 101st] Division and any change will result in serious loss of morale and efficiency both to the division and the battalion." Headquarters then agreed, and the "Bastard Battalion" officially became a member of the Battered Bastards of Bastogne.

This article was written by Martin F. Graham and originally appeared in the December 2004 issue of World War II.

Martin Graham's father was a member of Battery B, 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. He has extensively researched the battalion's history.

For further reading, try: The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, by George Koskimaki.

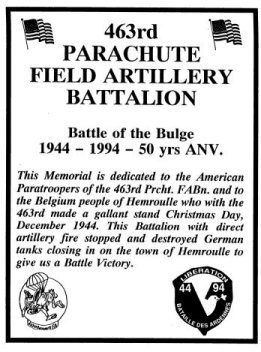

COMMEMORATING A CHRISTMAS LONG AGO

From the beginning of Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily on July 9, 1943, to final victory in May 1945, the men of the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion saw action throughout Italy, France, Belgium and Germany. At their annual reunions, they have shared many stories about their years oversees, but the one incident that always provides for the most discussion was the defense of Hemroulle early on Christmas morning in 1944. That action demonstrated the ability of a battle-tested airborne artillery unit to successfully confront and defeat a well-armed enemy force.

It had been a long-standing dream of the battalion commander, John Cooper, and Fred Shelton, a fellow Oklahoman and 463rd veteran, to in some way commemorate their action in this tiny Belgian village. Cooper and Shelton had a plaque created in 1995 and shipped to a Belgian native, Andre Meurisse, who had befriended the members of the 463rd over the years. They requested that he do whatever he could to have the plaque placed either in the village of Hemroulle or in the Nuts Museum in Bastogne.

Less than a month after his letter to Meurisse, Shelton received a confirmation from the acting mayor of Bastogne,

Philippe Collard, that the plaque would be placed on the outer wall of the chapel in Hemroulle that served as a hospital for both American and German troops following the Christmas morning attack. The dedication ceremony took place on Saturday, December 16, 1995, in the presence of Bastogne officials, representatives of the United States Embassy at Brussels, and the citizens of the town.

Although no member of the 463rd was able to attend at the ceremony, Shelton sent a letter to be read during the the dedication:

The German breakthrough of American lines near the tiny village of Hemroulle was perhaps the greatest threat to the "Battered Bastards of Bastogne" during the entire eight days they spent there while under siege.

"We of the 463rd can not forget the friendship and love that you gave us some 50 years ago, when you shared your homes, barns, cellars and church during the cold bitter winter of 1944 and early Jan 1945. I shall never forget a warm Belgium cook stove after a break in the battle where we were able to warm our freezing bodies and most of all our cold and freezing feet."

The plaque reads:

463rd

PARACHUTE

FIELD ARTILLERY

BATTALION

Battle of the Bulge

1944-1994-50 yrs ANV.

This Memorial is dedicated to the American Paratroopers of the 463rd Prcht. FABn. and to the Belgian people of Hemroulle who with the 463rd made a gallant stand Christmas Day, December 1944. This Battalion with direct artillery fire stopped and destroyed German tanks closing in on the town of Hemroulle to give us Battle Victory.

Those young men who fought in this tiny Belgian village will always be remembered for what they did on that Christmas morning in 1944.

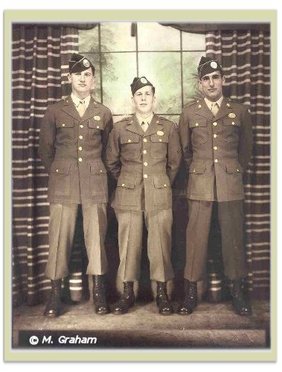

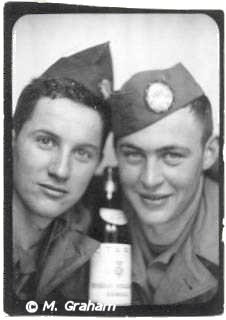

M.G.

M. Graham's Dad and friends in uniform.

M. Graham's Dad and friend holding shells.

M. Graham's Dad and friends.

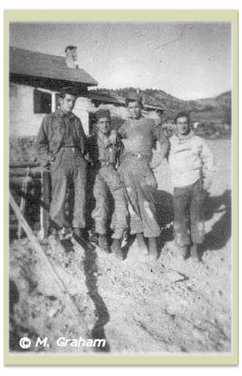

APPENDIX: some more pictures from Mr. Martin GRAHAM

M. Graham's Dad and friends outside of bunker.

M. Graham's Dad and woman in French resistance.

M. Graham's Dad and friend out of uniform.

M. Graham's Dad and unit friends in France

M. Graham's Dad and friend with a bottle of wine.

Germans K.I.A.

Same picture as above in the article, December 2004

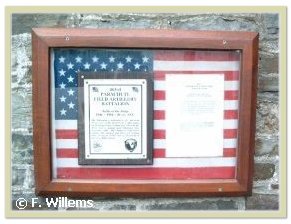

The print used for the (prior) Memorial

The memorial on the Chapel wall.

The memorial on the Chapel wall.

Other pictures (Ken Hesler, Roby Clam and webmaster)

The renewed memorial on the Chapel wall, as it is today

Trading Post Magazine (July-September 1987)

The article about the Battalion's insignia was published in the Trading Post Magazine in the July-September 1987 issue, and was provided to the webmaster by Ken Hesler (D/463rd PFA).

We have been granted permission to publish the article on the website by the ASMIC Adjutant, Mr. Scott Hughes, on August 12th, 2009. A big thank you to Mr. Hughes, and Kirk Kellogg, the author.

The website of the ASMIC - American Society of Military Insignia Collectors can be found at http://www.asmic.org/

Author’s Note: For the information and photographs contained in this article, the author is particularly indebted to the following persons, all of whom are veterans of the 456th/463rd:

Mr. William A. Kummerer, Dr. John S. Moore, Mr. Albert J. Toward, Mr. Kenneth Hesler, Colonel Hugh A. Neal, Colonel John T. Cooper, Jr., Mr. Joseph W. Lyons, and Mr. Douglas M. Bailey.

Any errors should be ascribed to the author.

THE 463RD PARACHUTE FIELD ARTILLERY BATTALION AND ITS INSIGNIA

KIRK KELLOGG

Background

The 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion was created on the Anzio beachhead from elements of the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. The nucleus of the 456th in turn was made up of men who had been in the original Parachute Test Battery.

The Parachute Test Battery was activated at Fort Benning, Georgia in the summer of 1942 and attached to the Parachute School for administration and training. The mission of the Test Battery was to develop a method whereby an artillery battery could land with all its weapons and equipment so that it could immediately go into action in support of parachute infantry.

The 456th was the Army's first large, regular-functioning airborne artillery unit, and it was activated on 24 September 1942 at Fort Bragg, North Carolina as a part of the Airborne Command. The battalion subsequently provided cadres for the first several artillery parachute units that were formed at Bragg.

North African and Sicilian Campaigns

The 456th left Fort Bragg in April 1943 as part of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regimental Combat Team. After a twelve day voyage on the Matson liner S.S. Monterey, it landed at Casablanca, Morocco and was then moved by rail to an area near the City of Oujda, on the border with Algeria. Here the unit continued its training in preparation for the invasion of Sicily. It was near Oujda that most of the men in the 456th made their first night jump.

From Oujda the unit was flown to an area near the City of Kairouan in Tunisia, where it camped in the hot desert for about two days before boarding C-47s for Operation "Husky." Taking off at around 2100 hours on the evening of 9 July 1943, the artillerymen arrived over the south coast of Sicily and jumped soon after midnight. Due to faulty navigation, high winds, and imparied visibility, almost all of the airborne units that participated in the initial assault came down far from their intended drop zones and were widely dispersed. Tragically, many of the paratroops and glidermen landed in the sea and were drowned. However, those that did come to ground uninjured coalesced into small groups and proceeded to roam the enemy rear areas creating havoc and confusion and leading the Axis High Command to conclude that their numbers were much larger than they actually were.

After the assault phase of Husky was completed, the 456th was sent to occupy an area near Trapani at the northwestern tip of the island. It remained there about one month before higher headquarters decided to transport the unit back to North Africa. Accordingly, the Air Transport Command flew Batteries C and D to Bizerte; however, as the result of a SNAFU the Battalion Headquarters together with A and B Batteries were landed on the airfield at Comiso near the south coast of Sicily. The resulting separation was to last about two months. During this time, the troops at Comiso had the opportunity to engage in direct fire anti-tank practice by shooting at old vehicles being towed at some length behind a truck. This practice would later pay big dividends in the snows of Belgium.

Finally, the elements of the 456th in Sicily were loaded aboard ship and transported back to North Africa. After the unit was reunited, it embarked on a Liberty Ship named the Anson Jones for a voyage to Naples, Italy. Enroute, the ship put into the Sicilian Port of Syracuse to load supplies and await nightfall. Passage through the Straits of Messina was timed to occur after dark in order to minimize the chance of air attack by German bombers which concentrated on that choke point during daylight hours.

Italian Campaign

Landing at Naples in mid-December 1943, the 456th marched to Santa Maria where it was attached to the Canadian American First Special Service Force (FSSF). For the next six months, the history of the 456th/463rd would be interwoven with that of the "Force." As expressed by one author and former member of the FSSF, "They were new to Force then but would in the coming months become as closely attached in common experience as artillery could manage with infantry."

The 456th joined the FSSF just before its assault on Hill 720, the western spur of Mt. Sammucro. This assault went in on Christmas Day of 1943 and was part of a general drive toward Cassino and the Gustav Line during which the role of the FSSF was to protect the right flank of the U.S. II Corps and secure the high ground covering an attack by the 1st Armored Division up Highway 6. Enemy resistance east of the Rapido River and the Gustav Line was largely broken by mid-January 1944.

Fifth Army had issued tentative orders reassigning the FSSF to II Corps for the impending assault-crossing of the Rapido River. For this crossing, the 456th was to be attached to the 36th Infantry Division. However, on the morning of 30 January 1944, both the 456th and the FSSF were unexpectedly ordered to Pozzuoli, a port staging area near Naples. At Pozzuoli, they were loaded on LCT's and LCI's, and at dusk they set sail. Their destination was the Anzio beachhead.

Anzio

Despite a bright moonlight night, enemy aircraft did not molest the convoy, and at daybreak it was anchored off the headlands of Anzio. By noon, the units had been unloaded and staged into an open field about two miles from the town.

On 2 February 1944, the FSSF with the 456th went into the line under VI Corps. The Corps order read: "First Special Service Force, with 456th Field Artillery Battalion (less Batteries C and D) attached, will relieve the 39th Engineer Combat Regiment night 2-3 February and defend right flank of VI Corps S of (Bridge 5) inclusive." The 39th Engineers had been in a defensive posture and were glad to turn over the area to their replacements.

The sector assigned to the Force extended about eight miles along the Mussolini Canal from Bridge 5 to the sea. This sector comprised about one fourth of the perimeter of the entire beachhead. However, despite the very thin spreading of troops - about one every twelve yards - and the much larger enemy formations arrayed in front of it, the Force and its supporting elements were a constant headache to the enemy through their effective fire and aggressive patrolling.

Creation of the 463rd

The 463rd came into being on the Anzio beachhead, and its creation calls for an explanation.

In the early part of 1944, Ridgeway's 82nd Airborne Division was in England preparing for the Normandy invasion. At that time, the 82nd had two glider artillery battalions but no parachute artillery. However, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division was still in Italy and had the 376th and the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalions. Ridgeway managed to have C and D Batteries of the 456th (together with the battalion's numerical designation) transferred to England with the 504th. The remainder of the 456th, consisting of its Headquarters along with A and B Batteries, were designated the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. In order to retain its original fire power, additional guns were obtained from the 45th Infantry Division to replace the ones taken by C and D Batteries. These were incorporated into A and B Batteries.

The 463rd was formally created at 1201 hours en 20 February 1944 at a location near the Mussolini Canal and about one half mile southeast of the small town of Borgo Bainsizza. Like the 456th, the 463rd was assigned to the Fifth Army and attached to the VI Corps. Major (later Colonel) Hugh A. Neal, who became Battalion Commander of the 456th about five days after the jump on Sicily, continued as commander of the 463rd.

The Anzio beachhead lasted four months to the day, and during this time it was essentially a defensive pocket on flat ground overlooked by two enemy held mountain masses. All parts of the beachhead were periodically subjected to enemy fire, and survival required burrowing into the ground for protection. The planning for the breakout from the Anzio beachhead called for the VI Corps told rive generally northward through the Velletri gap onto the Valmontone plain where it would cut Highway 6 to Rome. The mission of the Force and its supporting elements was to sweep the corps right flank adjacent to the 3rd Division by capturing Mt. Arrestino and then cutting across the Lepini heights to Artena.

On the morning of 23 May 1944, the breakout commenced, and the 463rd together with division and corps artillery opened fire in support of the FSSF attack. The initial thrust was to clear the area to the east of Cisterna as far as the railroad. During this phase, the 463rd provided effective support, particularly against a heavy concentration of Tiger and Panther tanks.

On 25 May, the FSSF quickly secured Mt Arrestino South of Cori whereupon it was ordered to advance directly upon Artena and leave the eastern heights to the French. Early on 26 May, the Force including the 463rd arrived in Cori and in the afternoon continued its advance on Artena arriving there the following day. Resistance to this point was light. However, during the night of 27-28 May, the Germans moved in tanks and flak wagons which began firing up and down the steep streets of Artena. The 463rd forward observers were well placed and proceeded to engage targets as fast as they appeared. Covering smoke enabled armor to accompany the FSSF attack which was slowed by an extremely heavy concentration of enemy weapons on a narrow front. By evening, a crescent around Artena had been largely secured, On May 31st, Major Neal, the 463rd Battalion Commander, was seriously wounded by an 88mm shell and had to be evacuated. He was replaced by Major John T. Cooper who had been the battalion Executive Officer.

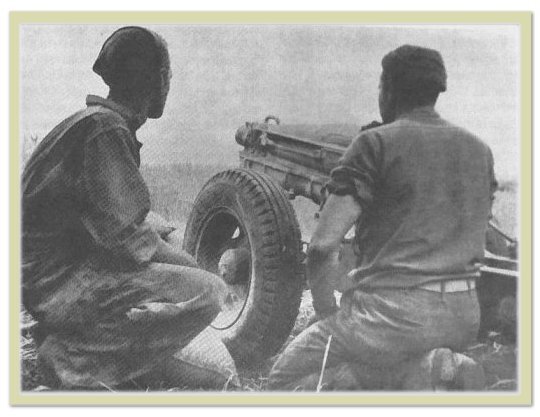

Picture:

463rd artillerymen near Cori, Italy.

Their "Pack 75" howitzer weighed only 1,268 pounds,

and it could be disassembled for airdropping.

However, its range with a 75mm projectile was only 9,475 yards

compared with 12,330 yards for the Standard howitzer

which fired a 105mm projectile.

Clearing away the resistance around Artena and Valmontone to the north was not completed until about 2 June and required heavy support from II Corps. Until the last elements of the German Tenth Army had passed through Valmontone enroute to Rome and beyond, the enemy resisted the cutting of Highway 6 with every possible means. During the ensuing attack on Valmontone by the 3rd Division on 1 June, the FSSF with the 463rd and its other elements had the job of securing the division's right flank

Fifth Army was now ready to commence its drive on Rome. With a front comprised of three corps, it planned to pursue the fleeing enemy through The Eternal City before he could reorganize on another line. To lead the assault, II Corps attached Task Force Howze to the FSSF effective 3 June. This Task Force was an armored group comprising elements of the 81st Reconnaissance Battalion and the 13th Armored Infantry under command of Colonel Howze. It was planned that the FSSF and Task Force Howze would alternate in the advance, with the armored elements driving ahead during the day while the FSSF advanced the point at night. With an enthusiasm akin to gold-rush fever, the units set out at top speed. By 1945 hours on the evening of 3 June, Task Force Howze had advanced fifteen miles from Valmontone and pulled up to let the FSSF take the night advance. By midnight the Force had reached Tor Sapienza, a suburb of Rome. At 0106 hours on 4 June the Force received orders to secure the six bridges over the Tiber River to the north of Vatican City. The combined force moved forward at daylight and entered the city limits at 0620 hours, coming under fire almost immediately from antitank guns. It was 2300 hours that evening before the Force had secured a total of eight bridges over the Tiber.

In commemoration of their achievement, a plaque was ceremonially placed on St. Paul's Gate In the middle of Rome on 4 June 1984 - the 40th anniversary of its liberation. The inscription on the plaque reads as follows:

First Special Service Force

In Memoriam

On 4 June 1944, the United States-Canadian First Special Service Force commanded by

Brigadier General Robert T. Frederick led Allied Forces of General Mark Clark's Fifth Army,

apart of Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander's Fifteenth Army Group,

in the attack to liberate The Eternal City. In this action Task Force Howze of the 1st Armored Division,

the 463d Parachute Field Artillery and city units of the Italian Resistance gave valiant support

as we breached the gates of Rome and secured the Tiber bridges.

To our brothers in arms of all nations who died in the battles of the Italian Campaign

we dedicate this memorial.

First Special Service Force Association

4 June 1984

Monte La Defensa - Monte Majo - Monte Sammucro

Anzio Beachhead - Rome

Through 5 June the FSSF, with the 463rd, assembled in the area of Tor Sapienza. The following day, they were relieved from combat and placed in Fifth Army reserve for a much needed rest and recuperation. For this, the units were moved to Lake Albano, about seven miles southeast of Rome and west of the Alban Hills. Here the Vatican summer palace overlooked black volcanic beaches which ringed the blue waters of the lake. Liberal passes into Rome were interspersed with a program for reequipping and retraining.

The FSSF and the 463rd parted company on 1 July 1944 when the Force was moved to a training area south of Salerno (the two units were to meet again in France). The 463rd remained at the lake until 15 July when it was moved by truck to Lido de Roma where training continued in preparation for the invasion of Southern France. Batteries C and D of the 463rd (originally transferred to England during the reorganization at Anzio) were activated on 21 July 1944.

Southern France

The invasion of Southern France - code named "Operation Dragoon" - was conceived as a means of putting large quantities of additional men and material onto the Continent of Europe. It was not felt that these could effectively be used in Italy, and the Channel ports were already operating to capacity. This left the South of France, which included the large Port of Marseilles.

The invasion was to open with an airborne assault by the First Airborne Task Force commanded by Brigadier General Robert T. Frederick (who commanded the First Special Service Force until about 23 June). Frederick organized and trained this composite unit in the amazing time of less than one month. The Task Force was to be transported in 535 C-47 and C-53 aircraft together with 465 gliders. It was to drop in the Argens Valley near Le Muy and Draguignan to block roads leading to the beachhead then attack the town of Frejus near the coast from the rear. The parachute troops were to jump at first light around 0430 hours and were to be followed by the gliders beginning around 0930 hours.

The First Airborne Task Force was principally comprised of the following units:

British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade

517th Parachute Infantry Regiment

551st and 509 Parachute Infantry Battalions

550th Glider Infantry Battalion

463rd and 460th Parachute Field Artillery Battalions

602nd Glider Pack Howitzer Battalion

On 11 August, the 463rd was trucked to the airport at Grosseto, about 100 miles north of Rome near the coast. Here, together with the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, they loaded aboard C-47 aircraft for the flight across the Ligurian Sea.

At 0425 hours on 15 August 1944 in scattered clouds and fog, one half of Headquarters Battery, all of A Battery, plus the 1st and 2nd Platoons of D Battery jumped in the vicinity of Le Muy, France. As the result of a navigational error, the other half of the Headquarters Battery, all of B and C Batteries plus the 3rd and 4th Platoons of D Battery jumped at 0430 hours in the vicinity of St. Tropez. Despite the inadvertent splitting of the 463rd into two parts, the unit managed to reassemble as a battalion by 17 August about 31/2 miles southwest on Le Muy. The Battalion Commander, Major John T. Cooper, fractured his ankle in the jump on 15 August and was replaced for approximately two months by Major Stuart M. Seaton, the Battalion Executive Officer. Upon his return from a hospital in North Africa in mid-October 1944, Major (later Colonel) Cooper served as Battalion CO of the 463rd until the end of the war.

After its reassembly, the 463rd worked its way up to the coast toward Nice with the Task Force. On the way, much larger and better equipped enemy forces were defeated, captured, or dispersed. Near Nice the 463rd and a glider infantry battalion were transported north into the Maritime Alps to fight as mountain troops for the next several months. During this period the men of the 463rd fought the "Champagne Campaign," which entailed combat with the enemy interspersed with occasional passes to enjoy the pleasures of the French Riviera just a few miles away. However, with the onset of winter, the 463rd was replaced by another parachute field artillery battalion and on 22 October 1944 was withdrawn from combat and moved by truck back to the south coast.

For a while, the men of the 463rd were able to relax and enjoy life on the Riviera without the distraction of the war. However, toward the end of November 1944, the First Airborne Task Force was disbanded, and the 463rd was attached to the 101st Airborne Division for administration and rations. The 101st was in north central France at Mourmelon-la-Petite, just to the east of Reims, where it was sent after Operation Market Garden in Holland. Traveling by truck from the Mediterranean Coast, the 463rd arrived at Camp Mourmelon on 12 December 1944. The weather was cold and wet. After a short but restful week, all hell broke loose to the north.

Battle of the Bulge

Late in the day on 17 December 1944, the 463rd was placed on alert as a result of the German breakthrough in the Ardennes. In mid-afternoon on the following day, the artillerymen departed by truck from Mourmelon, France and headed north. As they neared Bastogne the roads became crowded with retreating soldiers from units that had received the brunt of the German onslaught.

On the morning of 19 December, after an all night drive, the 463rd arrived at the temporary headquarters of the 101st Division Artillery on the road south of Bastogne only to learn that no plans had been made for positioning the battalion. On his own initiative, the 463rd Battalion Commander elected to continue on to the Town of Hemroulle, about 1.5 miles northwest of Bastogne. The unit closed into this area at about 1500 hours and set up its Command Post and Fire Direction Center in the town. On the following day - 20 December 1944 - the Germans cut the remaining road leading into Bastogne and completed their encirclement.

The 463rd was assigned the mission of providing artillery support to the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment whose sector thinly covered the west and south borders of the defensive perimeter. Initially, this support was limited because of extremely heavy fog and low clouds which prevented the Forward Observers from adjusting indirect fire. However, fire missions were conducted whenever targets could be. On the 21st, the Battalion commenced redeployment of howitzers into previously prepared direct fire positions from which they could defend against tanks. This was done because of the changing tactical situation and also because supplies of high explosive ammunition had dwindled to the point where they insufficient to support heavy indirect fire missions. Fortunately, the 463rd had some armor piercing ammunition which it had obtained in Italy. This ammunition had not been listed on unit ammunition reports, and it was soon to become very useful.

About noon on 23 December, the weather allowed the first aerial resupply drop flown by 241 C-47 aircraft. It arrived none too soon. Some guns had no high explosive shells left, and others had only a half dozen or so. Rations were totally exhausted. The sight of the colored supply chutes coming down gladdened the hearts of the paratroopers. At dusk on the 23rd, the Germans launched an attack from the south in an attempt to break through the 327th Glider Infantry lines, but this was halted by midnight with heavy losses to the attackers.

In the pre-dawn hours of 25 December - Christmas Day - the Germans launched a second all-out attack intended to wipe out the Bastogne pocket. This time it was out of the northwest and headed straight toward the 463rd. Eighteen Mk. IV tanks with supporting infantry broke through the thin defensive line of the 327th Glider Infantry and began to advance toward Hemroulle. After the initial breakthrough, little opposition was met, and the German tank infantry team with eleven of the tanks proceeded several miles to the outskirts of Hemroulle. Evidently mistaking the town for Bastogne, the tanks and infantry pulled off the road and halted. Their stopping point was only about 100 yards from several of the 463rd howitzers which were virtually invisible because of the darkness combined with a recent light snowfall. Incredibly, the German column remained in this position for over an hour. The battalion headquarters had been alerted to the presence of the tanks by an outpost guard, however, Major Cooper ordered that fire be withheld for as long as possible. This was done in hopes that the light of dawn would improve the hit probability and because of a concern that the tanks might, after all, be American. As the dawn broke, the outline of the German tanks and their distinctive muzzlebrakes made identification unmistakable. When the command to fire was given, the ensuing battle lasted approximately half an hour, and during this time many of the 463rd men fought as infantry. Eight tanks were knocked out by the howitzer crews and when one of the others received a hit which injured its commander, it was captured intact by an artilleryman who hung his undershirt on the tank's muzzlebrake and drove it back to within the battalion's defensive perimeter. Two tanks managed to escape the deadly fire of the 463rd but were destroyed by a rapid deployment armored force dispatched by Division Headquarters. Of the eighteen tanks which began the assault, none survived the day.

In the gathering darkness just after 1700 hours on the following day - 26 December - the first elements of Combat Command R of the 4th Armored Division broke through the German encirclement from the south and relieved the siege. During the period 19 December to 31 December 1944, the 463rd fired over a 360 degree sector, expending a total of 7,676 rounds of ammunition on almost every kind of ground target.

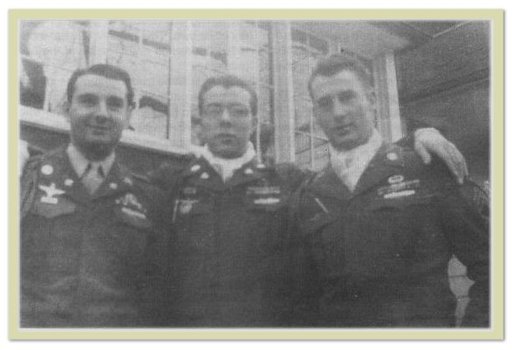

Troopers Richetto, Tower, and Kummerer in a 1945 photo.

Note the Italian jump wings being worn on the left side of the Ike jackets.

When asked why these wings were worn,

Bud Tower replied "to impress the girls, what else"

The victim of anti-aircraft fire, this C-47 crashed in front

of the 463rd positions at Bastogne.

Before it touched down, its tailwheel is said to have

caught a 2 1/2 ton truck and spun it around.

The driver of the truck emerged at a full run.

Epilogue

After Bastogne, the 463rd returned to Mourmelon, France, with the 101st Airborne Division. It was there that orders were received transferring the 463rd to the 17th Airborne Division for the planned jump across the Rhine River. However, Major General Maxwell Taylor interceded to have the 463rd remain with the 101st, and it did so for the rest of the war, including the Rhineland Campaign. Their line of advance passed through Liege and Aachen to the Rhine River and then up the of, bank toward Frankfurt. On VE Day, they were camped in some hills about 30 miles from Munich.

The 463rd was inactivated on 30 November 1945 in Germany, but its history was not to end there. On 18 June 1948 it was redesignated (less Battery D) as the 516th Airborne Field Artillery Battalion, an element of the 101st Airborne Division (Battery D was concurrently converted and redesignated as Company K, 506th Airborne Infantry). On 6 July 1948 it was activated at Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky and allotted to the Regular Army. Thereafter, its history was as follows:

-Inactivated 29 April 1949 at Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky

-Activated 25 August 1950 at Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky

-Inactivated 1 December 1953 at Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky

-Activated 15 May 1954 at Fort Jackson, South Carolina

-Redesignated 1 July 1956 as the 463rd Airborne Field Artillery Bn. Inactivated 25 April 1957 at Fort Campbell, Kentucky

The Insignia

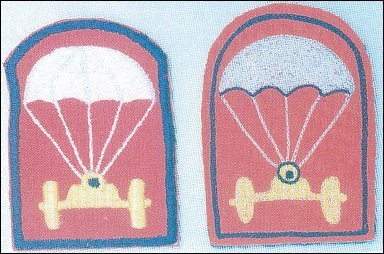

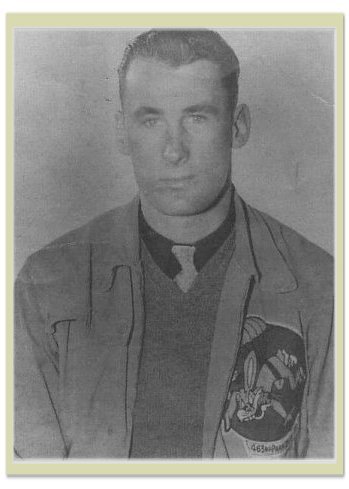

The 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion is not generally thought to have had any cloth insignia, however, two quite different patches were designed and actually made during World War II, and one of them was "formally" adopted - albeit many years later by veterans of the unit. One of the two patches featured a howitzer under a parachute canopy and was intended to be worn on the shoulder. The other was a large and colorful jacket patch featuring Bugs Bunny under a parachute canopy, and it had the unit designation on an integral tab at the bottom. Very few of these patches were made, and the originals are extremely rare.

The above patches were conceived by members of the 463rd after the breakup of the 456th on 20 February 1944.

Understandably, the breakup was not well received by the men of the unit, and one of the commanding officers later referred to it as "the rape of a battalion" The 463rd came to think of itself as a "bastard" unit, and there was evidently a feeling that something was needed to give it an identity of its own. This thought is what motivated the design and creation of the two patches.

There is some evidence that the idea of a separate patch for the 463rd was viewed with disdain by a few of the troopers who had been with the 456th from its early days. They still considered the 463rd - particularly C and D Batteries to be a Johnny-come-lately outfit. The Battle of the Bulge largely abolished such divisiveness.

The Howitzer Patch

The design of this patch is straight-forward and almost elegant in its simplicity. One glance leaves no doubt as to what kind of unit it represents. The design was conceived by the battalion surgeon, Dr. John S. Moore, while he was an the Anzio beachhead.

Picture : Dr. John S. Moore in a 1945 portrait.

By this time, the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery was wearing the 101st Airborne Division patch.

After Anzio, he mailed a rough sketch to his parents who lived In Washington, D.C. The following are excerpts from letters Dr. Moore wrote to his parents (their responses were not preserved):

23 July 1944: "Do you know of some company in the States which makes insignias, patches? We have been thinking up a patch to wear on our sleeves. The 82nd Div. insignia, which we used to wear, was removed after leaving the Div.

Most other divisions and separate units, like ours, have their own patches. We would have to design one and get it approved by the War Dept. which would probably take 6 months. However, we might be able to get one made up in the meantime. If you know of a company, or could locate one, that would be fine. The design will probably have a small field-piece suspended beneath a parachute - the parachute white, the gun yellow, and background red. Red and yellow are artillery colors" (this letter evidently enclosed a sketch.)

October 1944. "Thanks for getting (a family friend) to go to so much trouble. The drawings came the other day, but were not quite what we had in mind. I am enclosing a rough, color diagram. The view is head-on and resembles our howitzer. Of course, it never dropped as such, but the officers seem to like it this way rather than just the tube. The parachute could, perhaps, be a bit larger.

The suspension lines would be better if white instead of black as I have them. The red background is too dull a red. It should be a brighter red. The yellow of the cannon should be more of a golden yellow. The border of black around the cannon is there for contrast. The black border around the whole should be about as wide as I tried to make it. The whole design may seem a bit large but it is just about the size we want it. They seem to think it better without the number. If you could get (the same family friend) to improve on this and touch it up, fine. We made it as simple as possible, partly because we want it simple and partly because it would be easier to run off. Chances are we may never get a chance to have it approved or wear it, though; we have been shifted around so much of late."

28 October 1944: "(Your) letter contained the patch that Father has made up. I have not as yet had a chance to show it to the officers but will do so later. They have already expressed more interest in the other design, however, which you may have received by now."

20 November 1944; "Here is one of (family friend's) designs that I am returning. I have modified it a bit. The lines should be white, and not black as I have drawn them, but they should not come to central knot. I made the wheels a bit larger, and the shoulders a bit more square. The background should be a deep red and the piece a golden yellow. The ink lines I put on the 'chute are meant to represent the way the white threads should run. There are four panels, with what would look like a sort of part between them, as a part on a head of hair. That is the way that most of the parachute patterns are made. (My sister's) design was kept here because they want to get official approval on it."

17 December 1944: "About the insignia: I hope you had one of the new type made up as I would like to see it. However, we are attached to another unit, and if we wear any it will probably have to be theirs. Please have one made up, however. There should be no black outlining the parachute and no black along the suspension lines either."

28 February 1945: "Father's two letters containing the patches arrived last week. I turned one of them over to the battalion commander and kept one for myself. They are fine but we will not wear them because the unit to which we are assigned has its own insignia, which we have to wear."

Picture :

Two steps in the evolution of the shoulder patch conceived by Dr. John S. Moore.

The final design is on the right. The construction of these patches is quite different,

suggesting that they were made by different manufacturers.

From the above correspondence, it would appear that one of the suggested designs incorporated the battalion number. The patches which are pictured herein are those which Dr. Moore received from his father on 28 October 1944 and 28 February 1945. It is thought that only one or two of each of these were manufactured. They are very different in construction and were probably produced as samples by different manufacturers. Dr. Moore believes that his father had them made by a firm or firms in the Washington, D.C. area.

The officers club (a medical tent draped with parachute canopies)

at Mourmelon, France, after the Battle of the Bulge.

A party was given in celebration of a visit by movie actress Marlene Dietrich, seen here signing her autograph.

Second from the right is Major John T. Cooper, CO of the 463rd.

The Bugs Bunny Patch

The large colorful Bugs Bunny patch was the joint creation of two men, Sergeant William A. Kummerer and PFC Albert J. "Bud" Towar (rhymes with power). These men were assigned to D Battery, and shared the same foxhole in the Maritime Alps. During several discussions, they agreed upon the desirability of a patch and considered a number of different possible themes. Finally, they decided upon Bugs Bunny because, despite the indomitable hare's penchant for getting into trouble, he always managed to get out of it: and they were personally committed to having the 463rd and themselves endowed with the same ability! In a letter Bud Towar wrote to Bill Kummerer, dated 18 June 1982, he referred to this aspect of their idea by writing: " .. but still think the 'Bugs Bunny' patch is indicative of the 463rd - even to this day he has never lost a battle. If you recall, we picked him for that reason! In all his cartoons, he always starts out in serious trouble, but he always comes out of it the winner!"

Designed by Sergeant W. A. Kummerer and PFC A. J. Towar

while sharing a foxhole in Southern France, approximately 100 of these large

and colorful Bugs Bunny patches were made in 1944.

Kummerer and Towar made a crude sketch of their patch and mailed it to Towar's mother, Mrs. Mackie D. Towar, who lived in Grosse Pointe, Michigan.

Mrs. Towar forwarded the sketch to Warner Bros. in Hollywood where it was placed in the hands of Mr. Friz Freleng (Freleng was one of several people who originally created the cartoon character of Bugs Bunny). With the deft touch of a professional, Freleng finalized the design and sent an artist's rendering to Mrs. Towar. She then took the drawing to the Webber Knitting Mills located on Gratiot Avenue near 14th Street in Detroit and had approximately one hundred patches manufactured. These were put in a box and mailed to PFC Towar, reaching him about one week before the Ardennes offensive. Towar was not expecting the patches and initially thought that the box contained a cake. The patches were passed out, primarily to the men in D Battery, but also to others in the battalion who wanted them (it was always intended that the patch represent the entire battalion and not just D Battery). The ensuring German offensive in the Ardennes diverted attention from the patch, as well as all other extraneous things.

It is certain that the howitzer design was never worn as a patch. However, it was painted on a large board which was used as a decoration in the battalion officer's club. Some of the Bugs Bunny patches were sewn on field clothing. In a note to the author, Bud Toward wrote: "Although I am unable to find a picture of anyone actually wearing 'Bugs' during the war, I remember sewing one on my field jacket at Mourmelon. I also remember a direct order ... (through channels)... to remove it instantly! I remember not doing so at once, and perhaps that was one reason, out of many others, that I remained a PFC." In another recollection, it was mentioned that the Bugs Bunny patches were a little too large for the pockets of either the jump jacket or the newer field jacket. However, while the 463rd was attached to the FSSF, General Frederick arranged for the artillerymen to receive the same special clothing that the Forcemen were issued. Some of the FSSF parkas were still being worn in France, and these provided a larger area over the chest on which the patches could be sewn.

Back home in 1945.

On the far left is Bud Towar; on the left is Bill Kummerer.

These men designed the Bugs Bunny patch.

There is an epilogue to the Bugs Bunny patch story. In 1982, almost forty years after the end of World War II, the question of an "official" insignia was put to the members of the 463rd Veterans' Association. The matter was addressed in their newsletter and in the Static Line newspaper column, and various ideas were suggested. Finally, at the Chicago Convention held in August 1982, a vote was taken, and Bugs Bunny won.

A letter was written to Warner Bros. Inc., requesting permission to use the design, and Warner formally authorized it in a Copyright License Agreement. Small enameled pins and reproduction patches (reduced in size and differing in details) have since been made up, and the design is utilized by the Association in other appropriate ways.

Distinctive Insignia

Neither the 456th nor the 463rd had a distinctive insignia during World War II. Later, however, in a Quartermaster Activities letter dated 18 July 1956, submitted through the Commanding General of Third Army to the Commanding Officer of the 463rd at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, it was advised that the coat of arms originally approved for the 516th Airborne Field Artillery Bn, was redesignated for the 463rd Airborne Field Artillery Bn. The blazonry and description were given as follows:

SHIELD: Gules, in pale a winged cannon barrel muzzle to base or, each wing charged with three gunstones, in chief on a bezant, a fleur-de-lis azure.

CREST: None.

MOTTO: Satis Superque (Enough and More)

DESCRIPTION: The colors red and yellow are used for Artillery. The winged cannon barrel - muzzle to "earth" - suggests artillery from the "skies" and alludes to the airborne nature of the organization. The six gunstones represent six battle honors awarded the unit for service during World War II; the yellow disc and fleur-de-lis for service in Europe, also referring to the battalion's two decorations, the fleur-de-lis being blue for the Distinguished Unit Citation.

Originally approved for the 516th Airborne Field Artillery Battalion,

this coat of arms was redesignated for the 463rd in 1956.

Its basic colors are red and yellow. It was worn as a DI.

The record further indicates that samples of the distinctive insignia were approved by letter dated 26 May 1955, and the insignia was manufactured by N. S. Meyer, Inc. in New York City.

For the information and photographs contained in this article, the author is particularly indebted to the following persons, all of whom are veterans of the 456th/463rd: Mr. William A. Kummerer, Dr. John S. Moore, Mr. Albert J. Toward, Mr. Kenneth Hesler, Colonel Hugh A. Neal, Colonel John T. Cooper, Jr., Mr. Joseph W. Lyons, and Mr. Douglas M. Bailey. Any errors should be ascribed to the author.