The Test Battery, Basic Training, Activation of the 456 PFA

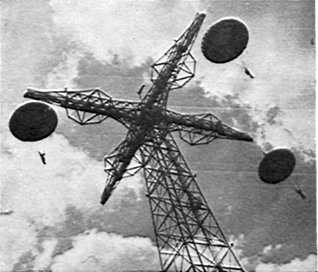

The Pack Howitzer Hits the Silk

By Capt. Lucian B. Cox and Lt. Herbert E. Armstrong, FA

Source: Field Artillery Journal (April 1943): 257.

If the men who designed the 75-mm. Pack Howitzer and the dauntless mule skinner who first "packed out" had seen a vision of what was subsequently to happen to their field piece, they might have renounced boots and breeches and transferred to QM for sake of sanity. The vision would have presented a far different picture from their accepted scheme of things. Instead of boot-clad redlegs loading the patient (?) mules, they would have seen lads in strange, green suits beneath an airplane placing the loads (wrapped in neat, oblong canvas containers) in udder-like blisters on the plane's belly. Instead of a slow animal column moving into a battery position, the vision would have shown men and bundles floating to earth beneath silken canopies from speeding airplanes.

Today this is no vision. Parachute Artillery is the latest weapon in our armed forces. It was designed to add the sting to the thrust of parachute infantry. In the winter of 1941 officers and men of the 4th FA (Pk How) Bn proved at Fort Bragg that the piece could be dropped from a bomber. The purpose of their experimentation was to develop a means of rapidly getting the howitzer into inaccessible places. However, if the piece could be dropped, why not the gun crews too? At that time parachute infantry was already a well-established part of the fighting units. Who ever heard of infantry without artillery support?

On February 24, 1942, the War Department authorized the activation of a test battery to conduct experiments to determine the feasibility of parachute artillery. Volunteers were accepted from the old Provisional FA Brigade at Fort Bragg, from which four officers and 150 enlisted men were selected. Naturally, these men had to meet the required physical standards for parachutists.

The first objective was to pass the Parachute Course, at that time given by the Infantry School at Fort Benning. None of the instructors pulled any punches in putting us through our paces.

The parachute course lasts four weeks or "stages." In the mornings of the first three stages the men learned the ins and outs of parachute packing and nomenclature.

Afternoons of "A" stage we devoted to tumbling, calisthenics, trampoline, and the much dreaded double-time.

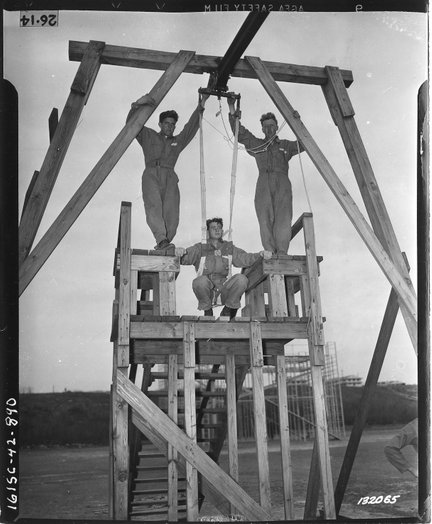

"B" stage offered training with devices such as a landing trainer (known affectionately as the death ride), trainaseum or "Plumber's Nightmare," suspended harness, practice in door exits from a mock plane, also more tumbling and more double-time.

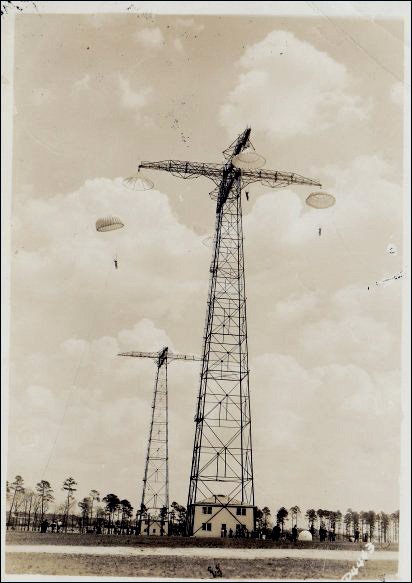

"C" stage took us to the two towers (now four) where we had our first real parachuting experience from the free tower, our teeth rattled by the "shock harness," and, incidentally, more tumbling and more double-time. At this point we were so groggy we would have jumped from a plane with a pillow case.

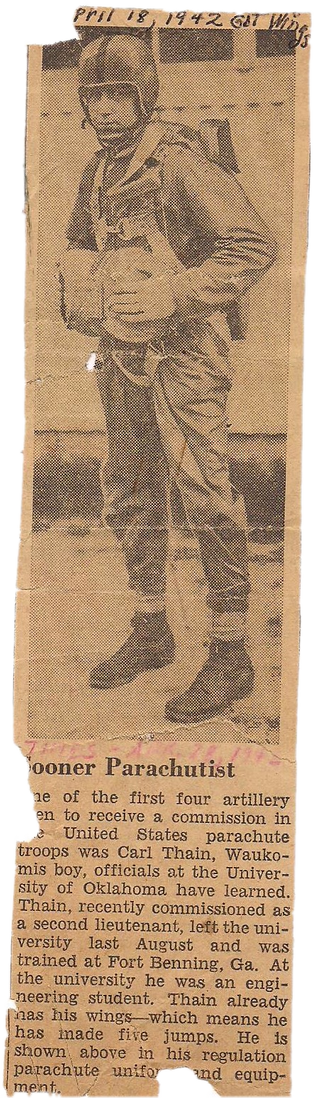

However, we were given the opportunity to test our 'chute-packing ability by making five jumps in the next week ("D" stage) from a plane in flight. Then, on April 17, 1942, the four officers and remaining 112 enlisted men of the Parachute Test Battery became the first qualified parachute artillerymen in the history of the Army.

After these preliminaries the real work began. Lieutenant Joseph D. Harris (99th FA) was the battery commander. The executive, Lt. Carl E. Thain (4th FA), SEE PICS had the problem of training cannoneers not only in the use of the 75-mm. pack howitzer (more than half of the men came from other than pack outfits), but also in their new duties in going into position from a plane. The main burden of the difficult job of compiling a T/O and T/BA fell to Lt. Lucian B. Cox (3rd FA Obsn Bn). Lt. Herbert E. Armstrong (3rd FA Obsn Bn) was the test officer.

The Infantry School appointed a board to supervise the experiments dealing with parachute artillery: Major John B. Shinberger (504th Prcht Inf), Captain Harry "Tug" Wilson (AC), and Lt. Armstrong. Major Shinberger became the godfather of the battery; without his initiative and contagious enthusiasm most of the work might never have been accomplished. Captain Wilson (often referred to as "the original army parachutist") offered technical advice coming from about 20 years' experience in experimental army parachute work.

Of course, many problems presented themselves. The first to be tackled was that of packing the howitzer itself for parachute descent. A detail was selected from the battery to work with Captain Wilson, Lt. Armstrong, and members of the Infantry Parachute Group. These men, under Cpl. James Denning, were Privates James Martin, George Alcorn, Wendel King, Anthony Koshinski, Gordon Roberts, and Robert Cogdell. The excellent work and initiative of these men is shown in all of the final results, and is still being shown.

During the first week the test section worked on packing and loading the plane. The type of aircraft used was the C-53 and the C-47 (similar troop transport aircraft). The plane was fitted with streamlined external delivery racks which could be attached to the bottom of the fuselage. From these were suspended six of the howitzer loads. The howitzer was broken down and the conventional loads were packed in standard Air Corps aerial delivery units --- cylindrical, padded canvas containers. Two of these, however, had to be adapted to fit the front and rear trails; end covers from the containers were placed on the ends of these two loads, but instead of felt padding around the middle, plain cotton duck was used merely to provide streamlining. Since the wheels were too bulky to be carried beneath the plane they were placed side by side in a small wooden cradle and thrown out the door. The breech block

was disassembled and packed in one of the delivery units; this was the only change from the standard mule loading.

Each load was hoisted by its points of suspension in order to test center of gravity and the method of packing. Following is a list of loads and their weights when packed for dropping:

Top sleigh and cradle 246 lbs.

Bottom sleigh 260 lbs.

Front trail 260 lbs.

Rear trail 181 lbs.

Wheels 200 lbs.

Tube 264 lbs.

Breech block 188 lbs.

The wheels parachute artillery howitzers are those with pneumatic tires. An aiming circle (15 lbs.) was padded and packed with the bottom sleigh. The parachute used was a standard 24-ft. cotton canopy.

Other equipment was tested too.

Although we had decided that a range finder would be excess baggage in a parachute situation, one was dropped packed in the same container used for howitzer loads, landing in perfect working order. This might throw some light on the controversy over the delicacy of the range finder. A complete test of the feasibility of parachute artillery would naturally result in the evolution of a T/O and T/BA for parachute artillery units. The principal factors governing particular personnel and items were:

(a) Can it be dropped by parachute?

(b) Is there available space and pay-load allowance in assigned airplanes?

(c) Is there available transportation after the initial parachute landing?

(d) Is it useful in the probable tactical employment of artillery units?

The first factor excluded only motor vehicles; small gasoline prime movers could be dropped, but they were eliminated because of other disadvantages. The factor of plane load limits coupled with the absence of ground transportation eliminated such items of equipment as cumbersome wire-laying equipment, powerful but heavy radio equipment, unessential fire control and topographical equipment. We found it to be a problem of a careful balancing of many factors. Since speed seemed of primary importance, lack of transportation after the initial parachute landing proved the most persuasive factor in the compilation of a T/BA. It was interesting to select a standard item of equipment and then try to justify its inclusion as essential. Often this preliminary consideration revealed that it was not only unessential, but also that even the basic field artillery unit might well dispense with its use as an unnecessary luxury.

Many items of equipment available to other branches of the service proved excellent substitutes for field artillery equipment which was too heavy or too bulky for our purposes. The suggestions and contrivances of our enlisted personnel were often invaluable in solving a problem of conserving weight or space. When enforced makeshifts proved so successful we began to see the infinite possibilities of parachute artillery with equipment designed for its specific needs. An excellent example of this can be found in the final selection of topographical equipment. After working for months with the only unit of its kind in the Army, the officers of the Parachute Test Battery decided that the topographical set "A"—with its dusting initial drop containers are sufficient to last until more are bro powder, many bottles of ink, calipers, a myriad of scales, pins, and drawing pens—would be about as useless in a parachute situation as a silk bedspread in a pup tent. A more adaptable set was selected to consist merely of range fans, small portable map boards, plotting pins, a few pencils, some overlay paper, and triangular scales. The number of items in the set would, of course, depend upon the number of personnel who need them. For want of a better term the requisition called this Parachute Field Artillery Set "A"; basis of issue: one per battery. Whether the powers-that-be will understand the need for this kind of adaptation and substitution remains to be seen. As far as that goes, we believe that in view of the situation about the only things an officer need carry with him in the way of fire-control equipment are field glasses, firing tables, and a map or photo if available. These, along with aiming circles, should be enough. If ever an officer had to "come out firin' from the hip," he will have to do it from an airplane.

Equipment from many branches of the service was examined, and many items were tried by the test section. It was not humanly possible in the time allotted to test all equipment which might fill even one of our needs. Often an instrument would be highly recommended by one office and as vehemently deprecated by another office. Whenever possible, actual field conditions were created for dependable tests of equipment. Often items were reluctantly omitted from the T/BA merely because they were not immediately available or because, in the absence of rigid field tests, a single voice of disapproval rendered that item's reliability dubious.

In addition to the factors already mentioned as governing the selection of basic items of equipment, we were agreed that every possible effort should be made to make each plane-load a self-sufficient howitzer section. Each plane should carry a complete field piece, ammunition, pioneer tools, instruments for indirect laying, communication equipment, and sufficient personnel to service the piece. We were able to accomplish all of these and our solution to the problem was submitted in our report to higher headquarters. Of course, the loading of the plane was limited by the weight factor so that it was difficult to pack more than 25 or 30 rounds in the plane loaded with the howitzer. However, a sufficient supply of ammunition can be carried in other planes and the 30 rounds in initial drop containers are sufficient to last until more are brought up in the planes immediately following. We decided that a howitzer with a dozen rounds is worth considerably more than half a howitzer with thousand rounds.

Much hard work and close collaboration between all men working upon the tests enabled us to evolve an entirely unique combat unit. Basic armament remained unchanged. The fundamental characteristics of Field Artillery remained. Yet a thousand of the smaller but no-less-essential items of equipment were modified, or substitute equipment used. Loading plans for this equipment provided for the contingency of planes destroyed before reaching an objective jump field. Thus, conceivably, a single transport might reach the objective and its one howitzer section land and deliver effective fire within ten minutes.

On April 23, 1942, a few spectators witnessed the first RSOP from an airplane. Two officers (Lt. Harris and Lt. Thain), two detail men, and a howitzer section under Sergeant Charles Raby (senior chief of section) made the jump. The howitzer loads were in the plane as described above. In addition a radio SCR-194, two telephones EE- 8-A, a small reel of wire, and an axle were packed in a small container, while the gun sight and BC 'scope head were packed in another.

These and the wheels were thrown from the door in a "daisy chain"—all bundles were thrown out at the same time, the opening action of the first opening the second, and so on. In 20 minutes the howitzer was assembled and the first simulated round fired. However, this was the first time. At present the average time is between 8 and 9 minutes, the best time being 5½ minutes.

It is useless to dwell upon the various trials and errors or the many experiments attempted. However, we did arrive at an SOP during the many trials and demonstration jumps the battery made. Early in the game we became more or less a flying circus, being called out to make a demonstration jump for practically anybody; this naturally interfered with experimentation. On the second jump Private Walter Blankenship volunteered to jump with the gun sight in a specially constructed case; he reported no

ill effects from carrying the additional weight down with him, and this became SOP from that time on.

All tactical jumps were made from an altitude of 800 feet, although combat jumps would be considerably lower.

Ground patterns varied with the velocity of the wind, the best (smallest) being within an area of 170 yards, which is

very good considering the conditions which govern the size of the ground pattern.

Twelve rounds of ammunition with fuze M-48 were dropped in the same type of container, suffering absolutely no damage. It seems likely that plane tables and most of the survey equipment would be merely burdensome in a parachute situation, so no steps were taken to test these for dropping. However, a small map board to be carried by key enlisted men and officers contemplated. On all jumps the officers carried field glasses.

Upon reaching the jumping point loads were pushed from the door of the plane, followed immediately by the first jumper. Other loads were being released from the bottom of the plane at the same time the men were jumping out. Each man was assigned a particular part of the equipment to bring to the assembly point. Various colored 'chutes were used so that the cannoneers could identify the loads they were to retrieve—they could spot these while they were still in the air and maneuver their own ‘chutes toward them. The chief of section would find the front trail and hold up its parachute so that the other men would know where to assemble the howitzer. Everybody, even the detail men and officers, would help in carrying the parts. After the howitzer was assembled the detail men would unpack their own bundles and go about their business.

Another consideration, that of transportation facilities upon hitting the ground, left little room for conjecture. The pieces obviously have to be man-handled. That, while somewhat difficult, isn't quite so impractical as it may sound. One night on a problem with the infantry, two of our gun crews showed that they could keep pace with the infantry even though the route was strictly cross-country, through ravines, woods, and streams for 12 miles. Although the men were tired when the objective was reached, they were in fighting condition. It seems very improbable that we will jump as far as 12 miles from our combat objective.

When the old provisional Parachute Group moved to Fort Bragg and became the Airborne Command, jobs were created for the artillery staff officers. Meanwhile the Parachute Test Battery continued to make demonstration jumps— more or less an orphan outfit, Lt. Donald A. Fraser joined us. It was at Fort Bragg that we had the experience of making our first night jump.

Finally — at long last — our patient waiting was rewarded. The battery was activated as a battalion. The old test battery had a rather good record to look back on. Very few of the men had been injured. Only a small part of the equipment had been damaged: some signal equipment was smashed because of a parachute malfunction; one howitzer was damaged when an inexperienced officer authorized releasing the six external loads at once.

Few of us have had the good fortune to feel that we were so essentially a part of something entirely new. Likewise, few of us have been so fortunate in witnessing the development of a new branch of the service, aside from the non-military questions of the physiological and psychological effects of parachute training and jumping. Only the fittest survive the test of the jumps, yet we were continually amazed by the morale and physical endurance of the enlisted men of the battery.

Perhaps living and growing with parachute artillery from its inception extends one's imaginative powers. Yet, with men like ours, all of the Axis armies could not prevent a parachute invasion of Europe. The tremendous assault and shock power of the rapidly multiplying Airborne Divisions will not be confined to the shorelines and prepared landing fields. Every square mile of Axis occupied territory is a potential bridgehead for the second front, for a dozen fronts. This new Army will establish its bridgeheads in the dark of night, riding on silent silken wings—and each bridgehead will be prepared for the armored car and tank to which the infantry had been so vulnerable. Engineer parachutists will be building landing fields overnight so that airborne troops may be poured into the breech. And, supporting the doughboys with its greater fire power, the Parachute Artillery will be hitting the silk.

LT Carl THAIN Pictures

Courtesy Mrs. Debra WINN, proud daughter of Lt THAIN.

My dad and Lou Cox at Ft Benning

My dad and another trooper - think it is Lou Cox and think it was in Africa

North Africa

My dad in the last stages of his army career

My dad with his sister, "Brownie"... a lot of the men knew Brownie as she was with Red Cross Evac hospital and always showed up to check on her brothers, Carl and Harold. This was in Normandy.

FROM PARACHUTE TEST BATTERY TO COMBAT OPERATIONS IN SICILY AND ITALY

Source:

CHAPTER 3 of the Thesis THE AIRBORNE FIELD ARTILLERY: FROM INCEPTION TO COMBAT OPERATIONS, by ROBERT M. PIERCE, LTC, USA, B.S., Cameron University, Lawton, Oklahoma, 1985

With the publication of the “Instruction Memorandum on the Employment of Airborne Field Artillery” in January 1943 by the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, the next step for the U.S. Army was to take the experimental doctrine and “determine the feasibility of parachute artillery.”1 The design of the new field artillery units was to add the necessary firepower for the parachute infantry. The officers and soldiers of the 4th Field Artillery (Pack (Pk) Howitzer (How)) Battalion successfully conducted a parachute drop of a pack howitzer in the winter of 1941 at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. According to Lieutenant Cox, the test batter executive officer, “The purpose of the experimentation was to develop a means of rapidly getting the howitzer into inaccessible places.”2 Though this drop happened as the doctrine was being written for the field artillery, no thought had been given, at that time, to drop the gun crews as well!

Realizing the need to incorporate the fire support arm with the parachute infantry, “the War Department authorized, on 24 February 1942, the activation of a test battery to conduct experiments to determine the feasibility of parachute artillery.”3 Four officers and 150 enlisted men were picked from a pool of volunteers from existing field artillery units at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to form the first test battery. These men were not parachute qualified or indoctrinated into the airborne culture at the time, so their first order of business was to become full-fledged parachutists.

The first task for members of the battery was to pass the Parachute Course at Fort Benning, Georgia. The course lasted four weeks and was divided into four stages, each lasting one week in duration. During the mornings of the first three stages, the men learned the art of parachute packing and the nomenclature for all items or pieces of equipment they would use. In the afternoon of Stage “A” the battery personnel dedicated their time to “tumbling, calisthenics, trampoline, and the much dreaded double-time.”4 “B” Stage provided training on such devices at the swing landing trainer, trainaseum (device used to train paratroopers on the proper technique for executing parachute landing falls), and suspended harness. In addition, the men practiced exiting procedures from a mock-up aircraft and did more tumbling and running. In Stage “C, the soldiers experienced the ‘free falling’ towers that took them up in the air to 500 feet and then released them (under canopy) to float to the ground, allowing the men to work on canopy control and landings. The last stage, Stage ‘D’, gave the future paratroopers the chance to test our ‘chute-packing ability by making five jumps . . . from a plane in flight.”5 At the conclusion of the final stage, 4 officers and 112 men of the Parachute Test Battery remained and on 17 April 1942, these men became the first qualified parachute artillerymen in the history of the Army.

The next challenge the battery leadership faced was training the cannoneers on the use and employment of the 75-millimeter pack howitzer, as well as developing techniques for conducting a parachute jump onto their equipment and getting the gun into position and ready to fire. On their way to accomplishing these tasks, many challenges presented themselves. The first order of business was to figure out how to disassemble and rig the howitzer for parachute drop. The aircraft the battery used were the C-53 and C-47 troop transport aircraft. Though the C-53 was mentioned, the C-47 was the predominant workhorse for the airborne. The plane was fitted with six streamlined external delivery racks, which could be attached to bomb shackles on the bottom of the fuselage. The howitzer was broken down into nine loads, M1 to M9, and “were packed in standard Air Corps aerial delivery units--cylindrical, padded canvas containers.”6 Two of the containers were modified to fit the front and rear trails. Appendix A contains the packing list used by parachute artillerymen to rig and drop the 75-millimeter Pack Howitzer and its associated equipment.

As the testing of feasibility continued the evolution of the Table of Organization(TO) and Table of Basic Allowances (T/BA) began to take form. The principal factorsgoverning particular personnel and items considered for dropping were:

(a) Can it be dropped by parachute?

(b) Is there available space and pay-load allowance in assigned airplanes?

(c) Is there available transportation after the initial parachute landing?

(d) Is it useful in the probable tactical employment of artillery units?7

Although vehicles could be dropped by parachute, they were subsequently discarded as nonessential due to bulk and weight factors that would change aircraft load plans and limit the number of artillerymen able to jump given the limited number of drop aircraft available. Leaving these large vehicles off the T/BA caused such things as heavy wire laying equipment, large radios, some heavy fire control, and topographic equipment to be deleted from the T/BA as well. As a fix, smaller and lighter items of equipment that belonged to other branches of service proved to be superb substitutes for the often heavy and bulky artillery equipment. Consequently, those items were added to the unit’s basic allowance. These changes did not, in any way, hamper or prevent the field artillery from performing its mission of providing accurate, responsive fires. All of the howitzer’s primary fire control equipment, such as sights and aiming circles, etcetera were not modified.

In addition to the factors previously mentioned as governing the selection of basic items of equipment, “we were agreed that every possible effort should be made to make each plane-load a self-sufficient howitzer section.”8 The leadership of the test battery recommended that each plane carry a howitzer, its tool set, communications equipment, ammunition, and instruments necessary to lay the piece indirectly (gun sights, etc.). Because of weight factors, only twenty-five to thirty rounds of ammunition could be carried on any one plane that had a howitzer loaded on it. The battery leadership felt that was a sufficient amount during the initial stages of the drop as other aircraft would bring in the balance of the ammunition. As Lieutenant Cox noted, “We decided that a howitzer with a dozen rounds is worth considerably more than half a howitzer with a thousand rounds”9 and were well aware of the risks and limitations associated with their decision.

A concerted, collaborative effort by everyone involved in the test battery project made possible the evolution of a unique combat unit. The fundamental characteristics of field artillery operations in terms of occupation of a position, laying the guns for directional control and the conduct of processing fire missions were still in place. What did change was a lot of the no-less-significant smaller pieces of equipment--they were either modified or substituted with more relevant items from other branches of the service. The loading plans the battery developed called for a complete howitzer and its crew jump or drop from the same plane. This enabled them to account for any contingency in the event any one aircraft did not make it to the DZ. Lieutenant Cox adds, “Thus, conceivably, a single transport might reach the objective and its one howitzer section land and deliver effective fire within ten minutes.”10

On 23 April 1942, the battery executed its first drop of both howitzer and personnel simultaneously with great success. This jump forged the way for more revisions in their dropping techniques. These revisions required officers and key leaders to jump with small map boards and binoculars and dictated the following actions for the gun crews upon reaching the DZ: door bundles were pushed out, followed immediately by the first jumper. As the troopers were exiting the aircraft, the bundles slung under the belly of the aircraft were being released. Each member of the howitzer section was assigned a responsibility to bring a specific piece of equipment to the assembly point. To assist each soldier, “various colored ‘chutes were used so that the cannoneers could identify the loads they were to retrieve-they could spot these while they were still in the air and maneuver their own ‘chutes toward them.”11 This technique proved quite effective during daylight training jumps, but would prove difficult during jumps in the middle of the night. The section chief would designate the assembly point when he located the front trail of the howitzer and held up its parachute so the rest of the men would assemble on him and the gun. Every section member that came to the piece would help out by carrying parts of the gun to the assembly point in order to expedite re-assembling the gun and gaining firing capability.

Since the test battery had not figured into their T/BA vehicles for airdrop, once the gun was assembled on the DZ, it had to be manhandled into position. This did not seem so unfeasible to the men of the battery for “it seems improbable that we will jump as far as 12 miles from our combat objective.”12 Little did they know what would await them on the night of 5 June 1944.

The test battery continued to make jumps, honing its skills until the battery was activated as a battalion on 24 September 1942. Despite all the tests conducted, very few men had been injured and little equipment was damaged. This was a tremendous achievement for the men and others associated with the test. Now a battalion, the airborne field artillerymen had the confidence that their new branch of service was here to stay and more viable than ever. As Lieutenant Cox argued,

This new Army will establish its bridgeheads in the dark of night, riding on silent silken wings-and each bridgehead will be prepared for the armored car and tank to which the infantry had been so vulnerable. Engineer parachutists will be building landing fields overnight so that airborne troops may be poured into the breech. And, supporting the doughboys with its greater fire power, the Parachute Artillery will be hitting the silk.13

Now that the War Department finally had the initial composition of an airborne division, its task now was to complete the organization of the division and find a suitable location for its home base. In the later months of 1942, the 82nd Airborne Division found itself moving from initial posts at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, and Fort Benning, Georgia, to its new home at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The organization of the division consisted of one parachute combat team and two glider combat teams (CT). Around 15 February 1943, “The 505th Parachute CT was substituted for the 326th Glider CT although the artillery (320th GFA) of this latter CT remained in the division. The division then consisted of the 505th PCT, the 504th PCT and the 325th GCT.”14

On 28 April 1943, the division left its home at Fort Bragg and began deployment to North Africa in preparation for future combat operations in Sicily and Italy. By 12 May the division had arrived and began to establish itself in bivouac at Les Angades Airfield, Oujda, Morocco (less the 325th GCT, which set up camp at Marnia). Additionally, they organized themselves into combat teams and Division Special Troops. The Division Artillery was broken down as follows: the 456th Parachute Field Artillery (PFA) was assigned to the 505th PCT, the 376th PFA assigned to the 504th PCT, the 319th Glider Field Artillery (GFA) assigned to the 325th GCT, and the 320th GFA was under Division Artillery Control. The combat teams of the division spent the next two months in “intensive training preparatory to parachuting into Sicily.”15

Pre-invasion training consisted of enhancing rifle marksmanship techniques, squad and section light machine-gun firing, mortar live fires, and basic close quarter combatives (hand-to-hand fighting). This applied to all paratroopers, including the field artillerymen. Their training day started early in the morning with a break during the heat of the day, followed by more training well into the night. Troopers spent the majority of their time firing their weapons individually and as part of a squad or section and were required to achieve a certain standard of efficiency in group marksmanship. Those subunits that failed to qualify had to retest until they could achieve the required standard. Troopers also conducted hand-grenade and bayonet training, as well as commando-type, hand-to-hand combat techniques for close-quarter fighting. The division also placed great emphasis on Battalion Combat Team (CT) training and it is at the battalion level that the field artillery batteries were able to move, shoot, and communicate as a battery instead of training on individual soldier proficiency. Once the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing arrived in theater, the division could begin combined training in earnest.

The wing arrived in the theater qualified for daylight operations involving parachute drops and formation flying over familiar terrain, but “unqualified for night operations.”16 In order to get qualified for night operations, the wing focused their efforts on night flying with emphasis on formation and navigational flying with navigational and resin lights. As it achieved a qualified status, the wing began to conduct nighttime parachute drops that were not without problems. According to the men of the 456th PFA, “These night-time exercises . . . brought to light a grave weakness in night-time parachute operations--it was extremely difficult for pilots to locate drop zones in the dark.”17 As a means to assist the pilots in identifying their intended DZs, the airborne community developed the pathfinder concept. This concept involved taking the most seasoned and experienced pilots and navigators and dropping a select group of paratroopers, known as pathfinders, onto a DZ. The pathfinders would set up the DZ by marking it with lights or setting up electronic equipment, so that the large aircraft formations could home in on the beacon or lights. Though this technique was not perfected for Sicily, it was put in use during the drops over Normandy.

Another huge challenge the division faced during its intensive training was coping with severe weather that included substantial, gale-force winds, which would whip over the barren North African landscape, making parachute operations extremely dangerous. In a report on airborne operations from Headquarters, Fifth Army Airborne Training Center, the after-action review noted that “two large daylight drops were made. These drops were made under adverse jumping conditions. The injury rate for parachutists was high and the division CG curtailed dropping”18 until such a time as the weather was within safety parameters. When the division was able to conduct parachute operations again, it did a nighttime drop and encountered many of the same problems as with the daylight drops--inexperienced flight crews had a hard time finding the DZ, winds tended to blow the jumpers off course and scatter the formations and the rocky, rugged terrain caused ma ny injuries which led to some fatalities. The men of the 456th PFA encountered the same problems as the rest of the task force--scattered jumpers, numerous injuries, and a tough time assembling in the darkness. For many of the troopers, this was their first time jumping during hours of darkness.

Sicily provided the supreme test in 1943 for airborne operations because it was the first time an American airborne division would conduct a nighttime parachute assault under combat conditions. The invasion plan called for the Seventh U.S. Army and the British Eighth Army to make a series of parachute assaults in conjunction with simultaneous seaborne assaults, on the southeast coast of the island. The parachute forces would jump in to seize key terrain and block any attempts of the enemy from reinforcing the beachheads, thus allowing the advance inland. The amphibious landings would cover an area that almost stretched over one hundred miles of coastline from Cap Murro di Porco located just south of Syracuse and around the southeastern tip of Sicily, west to Licata. The British troops would conduct their landing on the right with the American forces going in on the left. Immediate objectives were the ports of Syracuse and Licata, as well as the airfields between those two ports.

The airborne portion of the invasion plan, codenamed Operation Husky-Bigot, was a combined airborne operation of American and British forces with D-Day set for 10 July 1943. For the operation, the 51st and 52nd Troop Carrier Wings along with two British squadrons would be responsible for providing aircraft and gliders to both the American and British parachute and glider forces for the invasion. Because of their limited resources, only 250 C-47s were allocated to the 82nd for the entire operation. The small number of aircraft would constrain the division and force it to drop only one combat team initially, then sequence the rest of its combat teams into the fight with whatever number of aircraft that survived the initial drops on D-1. Thus the mission of the 82nd was to drop the 505th PCT, minus the 456th PFA, with a reinforced battalion from the 504thon the night of D-1 (9 July) “behind the Gela beachhead to block Axis counter-attacks”19 in order to support a 1st Infantry Division (U.S.) landing. The remainder of the 504th along with the 376th PFA was to be prepared by D-Day night to drop as directed on D+1 or D+2 behind friendly lines and act as a supporting ground unit. “Gliders were not even considered for use in the assault phase of the invasion,”20 hence the 325th GCT and supporting 320th GFA would be prepared to land on captured enemy airfields during daylight behind friendly lines on or around D+3 or D+4, once enemy air resistance was reduced.

With the details of Operation Husky in place and D-Day on the horizon, the men of the division moved to their staging base in preparation for the drop on 16 June 1943. The staging base was located as close to Sicily as possible, in Kairouan, Tunisia, where the Army Corps of Engineers had built makeshift airstrips. The division was still trying to qualify jumpers and aircrews during this time in order to avoid going into combat ill prepared and less than full strength. As a result, “the Regimental Combat Team (RCT) dress rehearsal of the 505th and 504th CTs jumps on DZs approximating those to be encountered in the actual operations were eliminated.”21 The division lost two weeks of critical training time just prior to the operation because the 52d Troop Carrier (TC) Wing was shuttling soldiers and equipment from Morocco to Tunisia and failed to take seriously the level of experience needed to drop parachute troops and equipment at night under combat conditions. Had the Wing taken a more serious approach in its training, the outcome of the operation might have been different.

Operation Husky began with violent windstorms developing over the Mediterranean Sea on the morning of 9 July 1943. Paratroopers of the 505th CT would make their first combat jump in severe weather conditions with winds at unacceptable safety levels in excess of twenty miles per hour. Despite the bad weather, the invasion was neither delayed nor called off. “In 226 C-47’s, the 505 Combat Team left ten airfields near Kairouan at dusk on the night of 9 July. The 456 (PFA) was widely dispersed among the serials--the firing Batteries prepared with 1512 rounds of ammunition.”22 The after-action report from the Fifth Army Airborne Training Center on Operation Husky provides the following in regard to the drop:

The takeoff was well conducted. By dusk the planes were airborne and formations started flying their course for Sicily. After dark, a heavy wind arose, flying was rough and men became airsick. No correction for the new weather conditions was made and formations began drifting off course. Difficulties became evident at Malta when many planes missed this important check point. Some pilots lost their elements and went alone. Several joined British formations and followed them to the east coast of Sicily. Over the beaches flack further distracted the pilots and the final drop resulted in units scattered from Gela to the east coast of Sicily.23

For the 505th CT, instead of being dropped over a five-mile area as planned, it was scattered over a sixty-five-mile area! Only a small percentage of men actually landed in front of the advancing 1st (U.S.) Infantry Division. Most were spread out all along the south coast of Sicily, disorganized, and disoriented. After the landing, the CT spent most of D-Day trying to assemble. Combat actions during this time were fought in small groups of paratroopers from different units or planeloads. Despite their misaligned fighting formations, the troopers of the CT attacked, with great ferocity, any enemy position they came across whether it be a pillbox, strong point, or roadblock. As noted from the Operation Husky report:

The Artillery had difficulty in assembling its 75-mm howitzers. The operation was slow and some 75s were never recovered. Artillery did get into the operation however, and hits on Mark Vs (German tanks) were scored by rolling the guns forward to exposed positions. The action as a whole was so scattered, the artillery was not given a fair test in this operation other than to demonstrate the need of transport for guns and ammunition.24

The 456th PFA encountered the same difficulties as the infantrymen of the 505th.

Units were scattered and the artillerymen spent the majority of D-Day assembling and organizing their units. Each of the three firing batteries (A, B, and C) lost one howitzer each, but had accounted for the majority of men and equipment by the end of D-Day. None of the batteries reported any significant challenges with finding their dropped guns or loads despite the scattered drops. A testament to the test battery design of having a complete gun and crew drop from one aircraft. The PFA battalion’s biggest challenge once sections had the guns put back together in firing configuration was mobility. As mentioned earlier, the test battery left prime movers off the T/BA, so any movement of the gun over any distance had to be done manually with section members either pushing or pulling the gun over all types of terrain.

When General Ridgeway came ashore from his command post at sea, he arrived at the 1st Infantry Division’s Command Post (CP) expecting to find 505th paratroopers and receive an update on actions thus far. He found hardly a soul. He had no success reaching Colonel Gavin by radio, so he set out to find him thinking the CT was pinned down near their DZs. He never found Gavin or any unit-sized element of the 505th. What he did find was scattered remnants of the regiment in no coherent form or organization. Seeing this, General Ridgeway notified General Patton, the Seventh Army commander, that he should cancel the drop scheduled for the evening of D+1. “Patton insisted he needed additional infantry,”25 so the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) along with the 376th PFA were ordered to drop into Sicily as planned. General Ridgeway assured Patton that he had notified both Army and Navy elements of the intended Allied drop on the evening of 10 July. The takeoff and flight of the 145 C-47s over to Sicily went as planned, but when the Allied aircraft started to approach the Sicilian coastline they were met by intense, friendly antiaircraft (AA) gunfire from both naval vessels afloat off the coast, as well as AA batteries along the beaches. Nothing could be done to stop the slaughter of the 504th. At least half of the aircraft were hit with the 376th PFA taking the brunt of the effects--over “half of the planes shot down had been carrying [their] artillerymen.”26 The experience was so traumatic for the men of the regiment that most of them were still in shock days after the mishap. The 504th, specifically the 376th PFA, was essentially rendered combat ineffective in the aftermath of the drop. Based on events that surrounded the 505th CT and the 504th PIR, General Ridgeway cancelled the glider landing scheduled for the next morning, D+2, for the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment. General Patton would have to survive without any further reinforcements from 82nd Airborne Division paratroopers for the rest of the campaign on Sicily.

The fighting in Sicily continued until 17 August 1943 when General Patton’s forces marched into Messina, hours ahead of General Montgomery’s British forces. For members of the 504th and 505th CTs, the fight was over. On 20 August 1943, elements boarded C-47 transport aircraft and flew back to North Africa where they would establish a bivouac and reconsolidate their forces in preparation for future combat operations in Salerno, Italy.

As the division began planning for the invasion of Salerno, Major General (MG) Ridgeway and Colonel Gavin were not too keen on having any of the parachute artillery jump in with them. In fact, no artillery from the division artillery would be used in the initial assault phase! The reasons for not taking the 456th into combat on Salerno was due to an altercation between the division commander and the 456th battalion commander in one of the battles at Sicily. It came down to a difference in artillery philosophy among MG Ridgeway, the division commander, and Brigadier General Maxwell Taylor, the division artillery commander, and Lieutenant Colonel Harrison B. Harden Jr., the 456th battalion commander. In essence, Ridgeway had been displeased with the actions of the gun crews at Trapani and felt Harden had failed to maintain discipline during the battle. Ridgeway wanted to use the 75-millimeter pack howitzers in the direct support role, much like mortars were used. Harden knew this was not the correct use of artillery employment and basically told his gun crews not to move and assume that sort of role. As a result of Harden’s actions and the in-actions of the gun crews, Ridgeway ordered Taylor to relieve Harden of command.

Once infantry regiments from the 504th and 505th secured the beach landing sites, the artillery would come ashore as part of the follow on forces. The operation in Salerno was successful, but did not bode well for solidifying the concept of airborne artillery supporting the infantry. Because the parachute and glider artillery did not participate in the initial assault on Salerno, there were no lessons learned to take away in preparation for the Normandy invasion. The only lessons the division artillery would take away were from the Sicily campaign. Those lessons were collected into a 5th Army Airborne Training Command memorandum and included the following: Approximately 5000 American parachutists were employed in the Sicily operation. . . . Sixty odd troop transports can be counted complete losses. Of all these losses, at least 50% could have been eliminated by proper training, planning and coordination.

- The execution of the Airborne plan as directed in field orders was very unsatisfactory due to the scattered dropping of troops. The results obtained by the 505th RCT after its drop however, more than justified the employment of this unit. Its aggressive action in rear areas dampened enemy morale . . .

- It is not safe to draw a general conclusion that scattering airborne units far and wide in rear of the enemy is a sound operation. Troops more determined than the Italians might have made short work of these small groups.

- The operation of the 504th CT cannot be considered satisfactory. Its losses were not compensated by any real damage to the enemy.

- Overwater routes for troop carrier formations should be a path ten miles wide, cleared of shipping and marked by vessels with lights every 50 to 75 miles . . .

- Airborne troops should never drop behind their own lines.

- Airborne troops and troop carrier groups should complete basic and unit training in the United States and arrive in the theater prepared for operational training.

- Glider training, to include night operations must be improved or glider units should be eliminated. With glider training at such a low standard, the Division Headquarters has no function. A parachute Brigade would be a more practical unit.

- A higher headquarters which commands Airborne, Troop Carrier and Air Corps Photographic Units would be of great value.27

It is important to note that given all the after action comments listed above, not one comment addresses lessons learned from the field artillery. Given that they had a scattered drop in Sicily and that they were not used in Salerno one can make the assumption that the parachute field artillery was not that effective overall.

On a much larger scale, a vital lesson the Allies were able to take away from the Sicilian campaign was the need for close cooperation and ability to plan, equip, and execute combined operations, such as airborne assaults and beach landings. But the most important lesson learned for U.S. forces, and specifically the 82nd Airborne was “how to organize and deliver our airborne troops.”28 Once Sicily was captured, the 82nd established a training facility at Biscari Airfield with the express purpose of training pathfinder units that consisted of experienced glider pilots and well-seasoned, dependable paratroopers. The pathfinder team was composed of one officer and nine enlisted men who were augmented by a security force, large enough and appropriately armed, to ensure mission accomplishment. The team would jump into an area twenty minutes prior to the main body parachute force and set up or establish the DZ by marking it with lights and electronic equipment that allowed the incoming aircraft to home in on the signal. This greatly assisted in reorganizing the force upon landing. In addition to the pathfinder concept, the parachute field artillery battalions developed a technique in which they attached colored lights to the paracrate loads during nighttime drops. The lights would activate as the loads hit the ground making it easier for the cannoneers to find the different pieces of the gun and facilitate a more rapid assembly of the crew and gun.

Another lesson the division learned was to immediately assault their initial objectives after they hit the ground. As they saw it, they had gained the initiative from the drop and in order to keep the initiative they needed to move on their objectives right away as opposed to waiting to assemble a sizable force before going on the attack. “The airborne experiences in Sicily proved valuable to us in our later battles and in helping train the green units and individuals coming from the United States.”29

The lack of focus and ability to train with experienced flight crews was the downfall of the Sicily operation from which many valuable lessons were learned--albeit the hard way. The actions of parachute field artillerymen proved the concept and doctrine sound, but questions would arise as to the feasibility of not placing howitzer prime movers on the units’ T/BA. It is also important to note the division’s failure to work more readily with the parachute field artillery in fixing the problems they encountered with lack of mobility and lack of ability to assemble fast enough to provide concentrated, effective fires. Given the fact that the drop over Sicily was executed so poorly, it was impossible to truly validate the concept of parachute or glider artillery. In that artillery was not utilized in the airborne assault phase in Salerno, the men of the division artillery (DIVARTY) would have to rely on previous experiences from both training and limited combat to carry them forward to Normandy.

Endnotes :

1 Capt. Lucian B. Cox and Lt. Herbert E. Armstrong, “The Pack Howitzer Hits the Silk,” Field Artillery Journal (April 1943): 257.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid., 258.

7 Cox and Armstrong, 258.

8 Ibid., 259.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., 260.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Headquarters, Fifth Army Airborne Training Center, Report of Airborne Operations, “Husky” and “Bigot,” 15 August 1943, 1.

15 General James M. Gavin, On To Berlin (New York: The Viking Press, 1978), 7.

16 Headquarters, Fifth Army Airborne Training Center, 3.

17 Starlyn R. Jorgensen, “History of the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion,” (unpublished), 52.

18 Headquarters, Fifth Army Airborne Training Center, 4.

19 Jorgensen, 52.

20 Gerard M. Devlin, Silent Wings: The Saga of the U.S. Army and Marine Combat Glider Pilots During World War II (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985), 78.

21 Headquarters, Fifth Army Airborne Training Center, 6.

22 Jorgensen, 57.

23 Headquarters, Fifth Army Airborne Training Center, 9.

24 Ibid., 11.

25 Jorgensen, 65.

26 Ibid.

27 Headquarters, Fifth Army Airborne Training Center, 12-13.

28 Gavin, 49.

29 Ibid., 50.

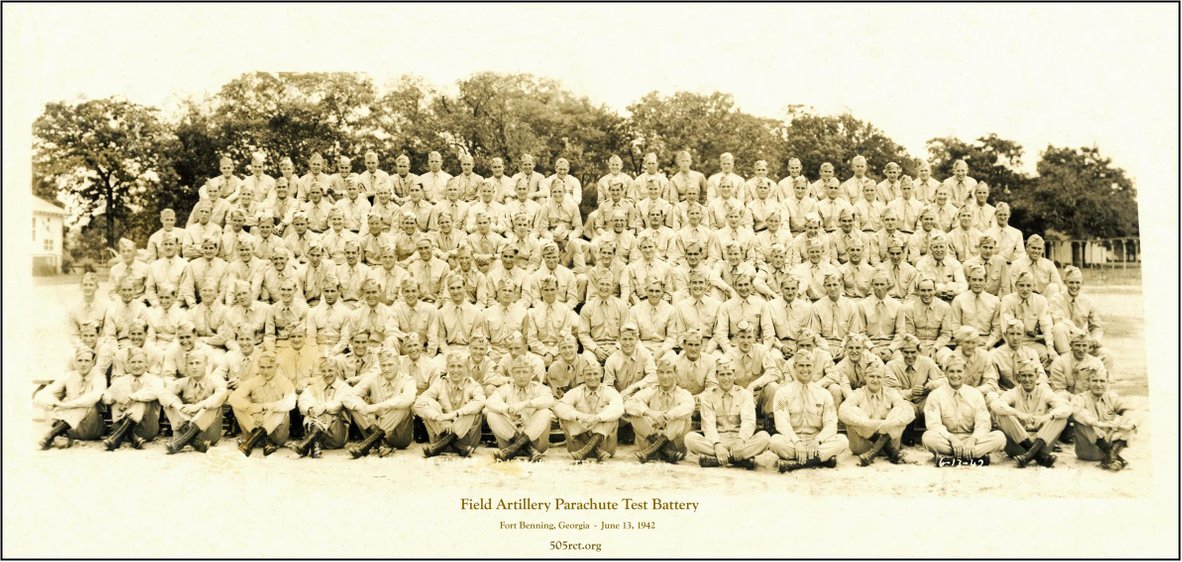

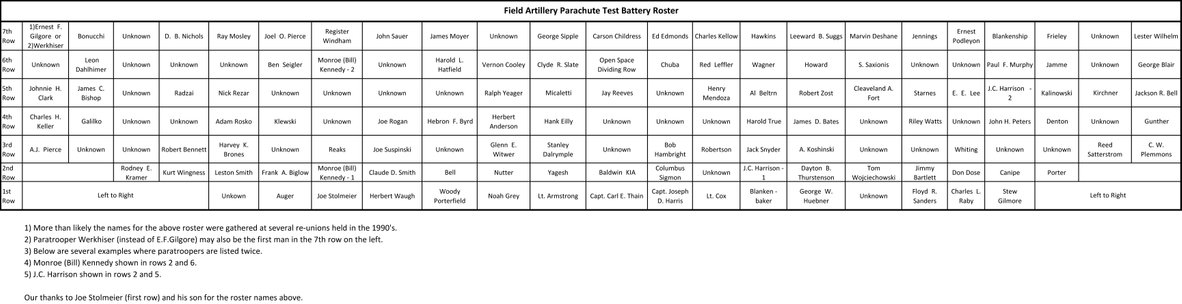

The TEST BATTERY members

Photo shown courtesy of George Sipple's daughter Carol and the 505 Regimental Combat Team Association.

Click to Enlarge !

A Condensed Chronology, by Martin GRAHAM

Based in large part on a collection of archival documents and other materials,

acquired and provided by Ken Hesler, Battery D, 463rd PFA.

DATE OF ARRIVAL | DESTINATION | MODE OF TRAVEL

February 1942

February 24 | Washington

War Department authorizes the activation of a test battery to conduct experiments to determine feasibility of parachute artillery.

Volunteers accepted from Provisional FA Brigade at Fort Bragg (4 officers/150 enlisted men) (FA Journal 257/260)

March 1942

March | Fort Benning, Georgia

500 volunteers become part of Class 12B (Infantry was class 12). Instructors from the 501PIR had orders to thin the class down to 150 qualified paratroopers. Since the infantry hated artillery, the instructors tried to eliminate everyone from class, but 143 men graduated. (Joe Stolmeier.)

April 1942

April 17 | Fort Benning, Georgia

4 officers/112 enlisted men of Parachute Test Battery became first qualified parachute artillerymen under command of:

- 2nd Lt. Joseph D. Harris - Battery Commander

- Lt. Carl E. Thain - Executive Officer

- Lt. Lucian B. Cox -

- Lt. Herbert E. Armstrong - Test Officer

Mission : to develop method whereby an artillery battery could land with all its weapons and equipment so it could immediately go into action in support of parachute infantry. The "Pack 75" was the chosen artillery piece. 1,268 pounds, it could be broken down into 9 pieces:

- Top sleigh & cradle - 246 lbs. (when packed)

- Bottom sleigh - 260 lbs.

- Front trail - 260 lbs.

- Rear trail - 181 lbs.

- Wheels - 200 lbs.

- Tube - 264 lbs.

- Breech block - 188 lbs.

- Aiming circle - 15 lbs. (packed w/bottom sleigh)

- Range finder

It's range was 9,475 yards. Harris developed procedures to drop his 108-man battery, 4 Pack 75's, basic load of ammunition, defensive light machine guns, and survey and communication equipment from 9 C-47 planes. Most of the hardware was fixed under the wings and bellies of the airplanes in padded containers which resembled coffins, and to which were affixed standard Air Force Cargo parachutes. The "coffins" were joined by a heavy-duty rope and dropped over landing sights. (Devlin 121/123;FA Journal 257/260)

Parachute Training:

A Stage:

- 8 hours of physical training or detail each day and the showing of a German paratrooper training film. Everything at double time. PT consisted of morning: an hour exercise, an hour run, 2 hours of various training (rope climbing, judo, grass crawls, log tossing, Indian clubs, obstacle course); afternoon: an hour exercise, an hour run, 2 hours of various training (rope climbing, judo, grass crawls, log tossing, Indian clubs, obstacle course).

B Stage:

- Mornings - 4 hours of exercise (calisthenics, running, etc.)

- Afternoons:

- Fuselage Prop - stand up on plane, hook up on static line, check equipment of man in front, responding to commands of jump master, making proper exit from plane.

- Landing Trainer - student hooked up in a jumper's harness attached to a roller that slides down a long incline.

- Mock-Up Tower - 38 foot platform with a long cable extending on an incline to a big soft pile of sawdust.

- Trainasium - 40 foot maze of bars, catwalks, ladders.

- Free Towers - 250 foot tower for making controlled and free jumps.

- Wind Machine - practice collapsing chutes.

C Stage:

- Mornings - 4 hours of exercise (calisthenics, running, etc.)

- Afternoons- Packing Shed

D Stage:

- 5 qualifying jumps.

Jump Towers (Courtesy: Peter Chuba)

On training (Courtesy: Don Gallipau)

April 23 | Fort Benning, Georgia

First RSPO from airplane with Lt. Harris, Lt. Thain, 2 detail men, howitzer section under Sgt. Charles Raby

Tranasium used in parachute troop training,

Fort Benning, Ga. February 5, 1942

Courtesy National Archives,

photo no. 161SC-42-889

(click to enlarge)

Deflating chute with aid of another parachutist, Fort Benning, Ga.

Courtesy National Archives,

photo no. 161SC-42-119

(click to enlarge)

June 1942

Pvt. C. H. THOMAS, 505th Parachute Battalion, tests his weight against his harness as he learns the trade on a landing trainer, an apparatus which simulates a landing. Fort Benning, Ga. February 5, 1942.

Courtesy National Archives,

photo no. 161SC-42-890

(click to enlarge)

Parachute troopers shown jumping from a plane. Fort Benning, Ga.

Courtesy National Archives,

photo no. 161SC-42-487

(click to enlarge)

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Brigadier General W. C. Lee review paratroopers before a demonstration jump staged for the PM’s visit. Six-hundred paratroopers under Brig. Gen. Lee’s command took part in the jump.

Once safely on the ground, the demonstration continued as the paratroopers simulated capture of an enemy-held field.

PM Churchill’s visit was a military secret at the time. A caption on the photo indicates it was taken at Ft. Benning, Ga. on or around June 24, 1942. The paratroopers wore parachutes made by Reliance Manufacturing, of Washington, Ind.

Source: Evansville Wartime Museum, Indiana. Thank you.

June 24 | Fort Benning, Georgia

Joe Stolmeier : Louisiana, Test battery, exhibition jump in front of Winston Churchill. Looking down the infantry that jumped prior was spread all over the place 50% not hitting the field. A typical jump was at 1200 feet, Joe goes to Lieutenant on the plane and says lets do it at 700 feet. He had been doing test jumps for months he new what would work, and what would break legs. So the Lieutenant agrees, they jump and all land just in front of the stands. Dad starts yelling to get the Howitzer assembled, they get them assembled, and roll them right up pointing Churchill. Everything changed after that jump; they went from limited personnel and hardly any equipment to loaded with everything they needed. (Courtesy: Aaron Stolmeier, son of Joe.)

September 1942

September 24 | Fort Bragg, North Carolina

456th PFA activated. Test Battery became B Battery, 456th PFA under:

- Col. Harrison B. Harden, Jr. - CO

- Maj. Hugh Neal - Executive Officer

- 1st Lt. Herbert Wicks - S3

- Capt. John Cooper - Adjutant (considered by Harrison to be the best officer he had)

Weapons:

- 75mm Pack Howitzer

- .50-cal machinegun

- 37mm anti-tank gun

- 2.36" Anti-Tank Rocket Launcher

- .30-cal Carbine

- .45-cal Pistol

February 1943

February 12 | Fort Bragg, North Carolina

Joined 82nd Airborne Division. Prior to going overseas, the artillery of the 82nd had to be given a proficiency test.

The test was administered by Hugh Neal. All units failed. Taylor and Ridgeway were mad at Neal for flunking the division artillery and dismissed him.

They ordered Cooper to retest which he did but the artillery once again failed. Taylor and Ridgeway ordered Cooper to change the grades, but he refused and was also dismissed. Prior to leaving for overseas, Neal and Cooper were reassigned to the 456th.

April 1943

April 22 | Camp Edwards, Massachusetts

Traveled by train.

April 28 | Camp Edwards, Massachusetts

Departed 6:00AM. Arrived at Jersey City at 1:30PM. Walked 1/2 mile to ferry to Staten Island, arriving at 4:00PM.

April 29 | Staten Island

At 4:30AM left USA as part of 505th Parachute Infantry Regimental Combat Team on the Matson liner S.S. Monterey. 6 men to a state room. Trip took 12 days.

We boarded the S.S. Monterey in New York for the 12 day trip to North Africa where we disembarked at Casablanca. On the ship they only served two meals a day, and we only had a bunk to sleep in every other night. The nights we did not have a bunk to sleep in, we just found a place on deck to sleep. The S.S. Monterey had been a cruise ship for the Matson line that went from San Francisco to Hawaii in peace time. It had been converted to a troop ship. There was about 5000 troops aboard, mostly out of my Division - the 82nd. (Doug Bailey)

GENERAL NOTES ABOUT BASIC TRAINING

Houser was West Point graduate as were his father and grandfather. Didn't want to be part of war. Killed self with pistol before being shipped overseas.

Soldier went home on leave before being shipped overseas. Found wife in bed with another man. Soldier killed both of them, his baby daughter and self.

Soldier brought a brand new 1940 car with him to Fort Benning. When in Phoenix City drinking, came back to car to find it on blocks with tires missing. Since couldn't find new tires, had to abandon car.

Officers enrolled in parachute school quickly realized that rank held no bearing. Lieutenants, Captains, Majors, Colonels were all subject to commands of noncommissioned officers.

Neil and Cooper tested the airborne field artillery for overseas. Failed them. (tape)

Jay Karp, trained as an infantryman, joined the 456th, B Battery at Fort Bragg. He was busted from corporal to private, but doesn't know why. (Karp tape)

Vic Tofany - The great Monk Meyer - All American guard at West Point - quit jump school.

Fred Shelton:

After leaving Camp Beauregard in Louisiana in 1943 I was being transferred to Camp Carson, Colorado to the 71st Light Infantry Division, which was being formed.

In my mind I thought this was going to be a hard hitting outfit or unit. How wrong I was. This unit or Division carried everything by pack boards, machine gun carts and other carts. They carried rations and other types of equipment and ammunition, and they had mortar bags which slip down over your head. It had pouches to put your mortar shells in.

Then after arriving in Camp, we began to take long strolls into the Rocky Mountains outside the Camp. Marching into the mountains it was an incline to start with. After you got into the mountains everything was straight up, rocky trails and tough walking.

After being in Camp about 6 weeks, one Monday we marched to some sheds and there we had wooden Jack Asses. At the end of the week we were told that we were going to have the privilege of taking the real live Jack Asses into the mountains for two weeks maneuvers.

Well, we went into the mountains for our two weeks holiday or celebration with the mules, the carts and full field packs.

While were in maneuvers it snowed and rained, and turned cold. The trails in the mountains became slippery and hard to maneuver on and the mules would balk and refuse to move on sometimes because of the weather conditions.

I remember one mule balked and the men were trying to get it moving. One soldier looked as if he were going to hit the mule in the nose and one old mule skinner sergeant said to the soldier, "Son you might as well slap your Colonel in the face as hit that mule in the nose." So then and there I began to realize that if I was to have an illustrious army career I was going to have to change branches of the service.

So, I began to think Airborne. I felt that I had rather fall out of airplanes with chutes than down the mountain side with mules. So then in mid-December of 1943 I got my orders to report to Fort Benning, Georgia for Paratrooper training. It was three weeks to the day after I signed up.

Now after some fifty years if I had another choice I would still go "Airborne" because they are a special breed of soldier.

Joe Stolmeier:

The 463rd didn't start with the 456th at Fort Bragg. The 463rd started at Fort Benning in March of 1942 in class #12B. The infantry class going through school at that time was class #12, so the artillery volunteers, numbering over 500 for that 1st Artillery Paratroopers class was numbered 12B, so they would be kept separate from the infantry jump class. Only 143 graduated, all the rest either quit, or were washed out. The instructors from the 501 had orders to thin the class down to 150 qualified paratroopers, & they followed orders real good, they worked us over more than any class that ever hit that place. The infantry at that time hated the artillery any way & those instructors told me artillery men weren't good enough to be paratroopers anyway.

They tried to disqualify all of class 12B, but couldn't get it done. I was the only artillery man stupid enough to insist that my sergeant's stripes stay on no matter what. All the other non-coms took their stripes off, as some officer instructor ordered. Not me! I spent 2.5 yrs in the National Guard and 1 of them in the swamps of Louisiana earning those stripes & no one was going to make me take them off. Boy what a mistake that was. It seems those instructors dressed in black sweat pants & black sweat shirts were not non-coms & they hated sergeants more than they hated artillerymen, so many a night after all the other guys were asleep on their cots, I would be finally released from running around the parade ground holding a rifle over my head, & doing push ups, & having as many as 3 of them at a time practice jiu-jitsu on me. I'd crawl up the stairs on my hands and knees and leave blood on the stairs, & then the next morning, before I could go to breakfast I would always have to clean the blood off the steps to the staff sergeant's satisfaction, or no breakfast, sometimes I was too late & the mess sergeant wouldn't let me in. I think they had it worked out between them.

When we formed the 456th, 2nd Lt. Lt. Harris (VMI) declared we were no longer Test Battery we were B-Battery 456th Battalion then immediately I was taken out of B-Battery and told I could pick 10 men to form A-Battery and they sent a Lt. I had never seen before to introduce himself, it was Stuart M. Seaton from VMI and he was sharp and he was a qualified paratrooper I was to be his 1st Sergeant & I was one happy GI.