Attended Catholic Schools:

Primary - St. Salome's 1926-34.

Won Monroe County spelling contest in 1933

Secondary - Aquinas Institute 1934 -38 Played on the football team College Entrance courses. St. Bonaventure University 1938-42 B.S. Chemistry 4 years ROTC. I was inspired to become a physician while hospitalized for an operation in 1935; so pursued Premedical curriculum. My child hood in a family of 5 boys was fun and educational in life. When I was 5, the depression hit and my father became jobless. I had started caddying when I was 8 and earned money for the the things I wanted which my parents could not afford.

Faced with the loss of our home, my parents sold our suburban home and moved into a 100 year old farm house with an acre of property which allowed us to produce much food for the table from our garden fruit trees and poultry. I worked for the farmers near us and became a strong and capable teenage boy.

Despite the non-prosperous situation, we enjoyed many opportunities for sports and other activities in which growing boys participate.

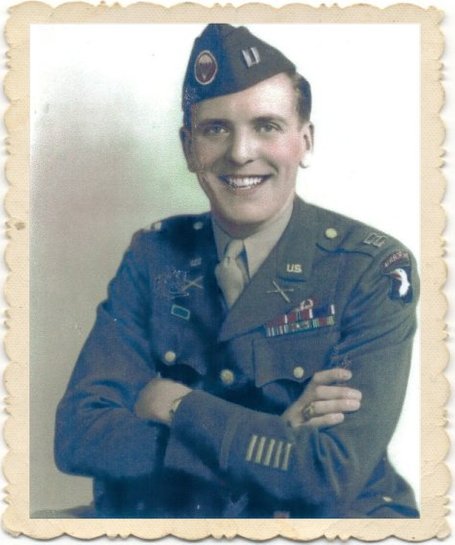

Trooper Captain Victor J. TOFANY

May 8, 1921 (Rochester, N.Y.)

In the process, we developed ambition, work ethic, and exciting goals which fostered educational desires and future opportunity, as well as mature interpersonal relationships.

My father was a World War I veteran, so when we went to college we joined the ROTC program. On December 7th 1941, All the ROTC boys donned uniforms and marched the dormitory halls singing and shouting. They were ready ! In retrospect, everyone jumped into the spirit of war and the sacrifice that came with it. My older brother and I were in the military, immediately, and the other 3 volunteered : one Navy , two Marines.

The mobilization of people and resources which immediately followed, was a feat bordering on miraculous. Industry and civilians alike embarked on a war effort we could only imagine and hope for. At the time I thought this was a “holy” war. Nothing has happened since, to change my mind.

General Ulio, the Adjutant General of the Army, delivered the commencement address May 29th 1942 and presented our 2nd Lieutenant Commissions along with orders for duty.

I reported for duty 6/29/42 and was assigned to a Field Artillery Replacement Training Regiment at Fort Bragg, N.C. There, I immediately attended a refresher course for officers which eased our entrance to official duty. While on a field problem, I encountered a Paratrooper running along the railroad tracks. He and his buddies were returning from a jump at a DZ near Fayetteville and they were returning to their bivouac area. This wiry little guy was running with both hands full of canteens trying to catch up to his buddies (I guess he drew the short straw). He said they had to be back at a certain time or they went on a hike that night. I was assigned the “old men's” platoon (38 year old men with beer bellies) at the time and when I saw the vigor and attitude of this fellow, I thought “This is the type of person, with whom, I want to serve.

I found out that they were recruiting volunteers for the Airborne; applied and promptly got orders to Jump School. When I finished Jump School, I was ordered to attend parachute rigger school. This training prepared me for a very interesting and exciting participation in development of equipment with which to deliver materiel (today the military calls them “assets”) to the DZ (drop zone) simultaneously with the Troops. However, it would later cause chagrin when I found out, I would be the rear echelon commander while my buddies went to the Invasion of Sicily. My best friend, Lt. Derby was KIA and I had the sorrowful task of preparing his personal belongings for disposition. The unpleasantness of war had arrived.

When I completed rigger school, I was assigned to the Test Battalion at the time it was in transition from the Test Battery. I was named Assistant Parachute Maintenance Officer. A large group of personnel arrived at the same time and we were all full of pioneering spirit, knowing we were part of new and exciting military endeavor. I, personally was enjoying the experience, as most 21 year olds would. Shortly thereafter, I was promoted to Parachute Maintenance Officer and continued in the development of new equipment for airborne delivery in combat. I had a section of very willing and capable parachute riggers who could turn out new harness and canvas containers promptly and of high quality.

Things were moving fast and, after continuous visits from upper echelon brass, we found ourselves part to the 82nd Airborne Division. I think this may have stunned some of us. We had the current development program on our minds and here we were joining a combat Division. Consultants from Rock Island Arsenal visited and took measurements etc. for the design of plywood containers for airborne delivery of some of the equipment. And a crash program of all the drop equipment was started. Meanwhile the engineers at Rock Island Arsenal were manufacturing plywood containers for dropping the guns and instruments.

Our field training continued and in April 1943 we had our overseas orders. We moved to Camp Miles Standish for staging with complete removal of all unit distinguishing things including jump boots, patches etc.; i.e. a secret move. That characteristic (secret) disappeared the first night, when a group of men encountered some amphibious troops at the PX wearing jump boots. Apparently the men were quite chagrined to see other troops wearing their distinctive footwear and after some conversation with the amphibious soldiers stationed there proceeded to involuntarily modify their boots to low cuts. So much for secrecy.

We then proceeded to a New York City port and embarked under darkness on the S.S. Monterey for the convoy to Casablanca. On the high seas we had the convoy position on the port side of the battleship Texas. This gave a glimpse of some things which introduced us to the war e.g. a submarine attack one night with depth bombs and multiple lights and activities on the Texas. Another, the daylight crash of the reconnaissance seaplane carried by the Texas which eventually was dumped into the sea.

The on board personnel management involved mass movement at appointed times to meals, deck positions (one night on deck-one night in hold) and bunks (3 tiered in the converted staterooms). Every day, at sundown, the garbage and trash was dumped off the fan tail to preclude sea gulls visiting and attracting attention during daylight.

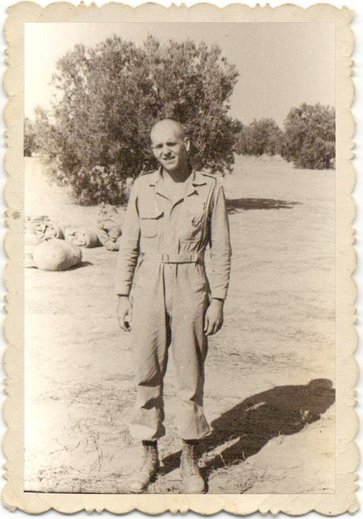

When we arrived at Casablanca, we went to a plowed field outside of town and established our first bivouac (pup tents) and opened our C-rations. Welcome to the war ! We moved to Oujda and then to our training area in Karouan and learned how to deal with flies, heat and slit trenches. Our training was suspended every several days for parades. I think every field General in the ETO reviewed us. General Patton gave a post parade lecture to the Officers on what our future action would be in very colorful language.

The living conditions prepared us for the hardships to come. Reveille 1st call signaled a mad rush to the slit trenches. The C-rations didn't put weight on anyone and showers were infrequent.

Karouan, North Africa.

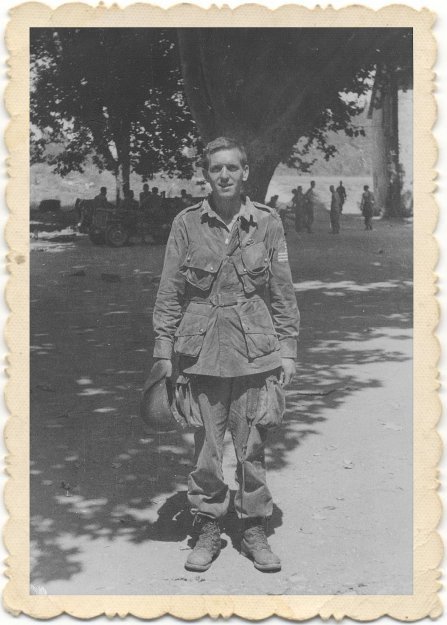

I was in charge of the Rear Echelon for the 456th during the Sicily Invasion, August 1943. My CP was the olive tree in the rear.

We received several new Officers and one of them asked me to cut his hair.

I started by using the clippers straight down the middle of his head.

I compensated him by allowing him to do the same to me.

We killed some quail that were feeding under the olive trees and had the first fresh meat since we got off of the boat in Casablanca

(the M1A1 carbines left the breast, if it hit them right).

The pack rats slept with us under the trees.

(This is where I prepared Lt. Derby's personal belongings for disposition).

Around 500 parachutes were delivered to us and, by command of Colonel Harden, drop-tested. This kept the parachute section busy and , hopefully, assuaged the fear of equipment failure at the time of the invasion, it also provided valuable experience for the rigger personnel and myself. I had the duty of jumping the chutes of anyone who refused to jump in order to preclude faulty equipment as an excuse. Refusers were subject to court-martial for refusing a direct order. I rather enjoyed this duty, since I didn't wear any equipment and had a Jeep waiting for me on the ground.

One interesting event occurred during a jump involving my riggers. One of them in my plane refused to jump. After we landed, as the Jumpmaster involved, I reported it to Captain Garrett, Hqs Battery Commander. He summoned the “Refusee” and, in my presence, informed him he would be court-martialed for disobeying my order. In refusing during a jump, the soldier jeopardizing the safety of the whole operation. It usually resulted in subsequent removal from Jump status as well as military discipline (court-martial). The man pleaded for another chance to jump. He stated that he didn't want to quit; but felt ill that morning. After grimly rebuking him, Vic Garrett offered him another chance. That afternoon the 3 of us went to the airfield, enlisted our Liaison Officer to act as jumpmaster. The plane took off and promptly approached the the nearest designated drop Zone The jumpmaster gave the order to “stand in the door”! I would jump first, the soldier next and Vic last. Just before I jumped, I noticed Vic had his hands on the outside of the jump door with the soldier sandwiched between us. When the “Go”! order came the 3 of us popped out of the door. 'There would be no refusing this trip. We all landed close together and that soldier was the happiest man on the planet. He thanked us profusely and assured us he would not fail again. He was a model soldier henceforth. I think Vic liked to jump; and felt it would be good for the morale of my closely-knit group. Sometimes a little compassion can go a long way.

There were several training jumps during this period. I recall one night jump which seemed to portend the difficulty of C-47 navigation during jump operations. Lt. Crossman's ship got lost from formation and flew quite a while before it was evident they were lost. Finally the pilot gave the green light and Lt. Crossman, being alert to the situation, refused to give jump orders. Apparently C-47 pilots didn't like to land with belly loads still attached, which seemed to be what happened. When the plane finally found it's way back and landed, the angry pilot threatened Lt. C. but, cooler heads prevailed and nothing happened to Lt. C. who explained his actions. Only the Lord knows where those troopers would have landed in that mountainous country. There has been a lot of post war discussion about this topic, especially among the members of the C-47 Association. I think it is only one of the many problems which accompany a new type of warfare. Unfortunately, the learning curve in the military has grave consequences and reflects why training safety is emphasized.

When D-day came, I was left behind with the parachute equipment in charge of the rear detachment along with similar personnel from the 505. Eventually, we moved to the Bizerte area where we remained until the move to Naples. At that point, we operated as ground troops until the Southern France invasion. While still in Hqs. Bty, with parachute equipment in storage, I did forward observation duty. I was pleased to get my opportunity to serve in combat. My first FO experience came on Christmas Day 1943 on Hill 1205 near Venafro, Italy. I arrived at the summit shortly before sundown and settled into the cave that would be my shelter. As dusk settled in, I spotted my first target – an artillery battery in the valley below. After adjusting and firing “for effect”, Vic Garret blasted the target for an hour. The last time I saw any activity in that area.

When I got to Anzio, I was assigned to A Bty and learned the art of forward observation from Lt. Sheppard. It was at this time, that I received a Purple Heart. While observing from a very forward position, firing multiple “targets of opportunity” and enjoying it, I was besieged in my farmhouse OP by a German tank. When I retreated from my perch in the attic to the rear of the house, near an open side door, a shell landed just outside the opening and a small piece of shrapnel entered my scalp. I scampered back to the main position and the Regimental Surgeon removed it; after determining that it had not penetrated my skull. I currently refer to this as my “Kerrey Purple Heart”. My brother in the 4th Marines had been wounded several weeks earlier and my mother had a very difficult time when the notification came. The Surgeon was very understanding; and by treating me at the Aid Station, precluded the official notification from reaching my parents. (years after the war; when her 5 sons were back from the war, established, and enjoying life, she would develop unremitting Depression which would end with her suicidal death).

Anzio was a difficult situation because of the terrain. Daytime activity required remaining in the canals to avoid observation. We later saw the railroad artillery piece, nicknamed the “Anzio Express”, on the way to Rome. Spring came and everyone became a little restless because of the inactivity; but the indomitable GI found solutions for daytime inactivity. Shell clusters had a metal bolt which made a good stake and the shell safety clips served as “horseshoes”. Voila' a game with some action to break the monotony. 4 man was the format and the Officers were enticed to play whenever they were available. The losers had to do push-ups ( the number was set beforehand). It was rather routine that the Officer's team lost which brought forth cheers as the Officer paid his penalty along with his partner.

I wasn't at Anzio when the 463rd was formed.

Warm, dry weather arrived and we were off on the offensive to liberate Rome. Vic Garrett had fire control for the massive Corps Artillery assigned to the operation. Our offensive stopped the 1st afternoon at Highway 7. The next day I started with the 45th Regiment and after crossing Hwy 7 with my corporal, retreated when the platoon from the 45th retreated under heavy fire from hull down tanks. It was at this time that my corporal was killed while we took air bursting fire from the tanks. Later that day a column of Mark VI tanks came from the opposite direction and starting forming a line on Hwy 7. We called Fire Direction and Garret turned his corps of artillery loose. The sun went down as the area of the highway became a cloud of dust. The Artillery fire continued all night (Vic ran several outfits out of ammo ) and at dawn the enemy had vanished. Several hours later, we passed through a T intersection up the road where Lt. Rosen in the observation airplane caught a massive road jam with the retreating troops from the south and those we were chasing from the west became fodder for the artillery. The mass of destroyed vehicles with incinerated troops in them and mangled bodies was indicative of the havoc being wrought by the advancing Allied troops...

The ensuing march to Rome was a well organized advance with intermittent pauses as the fleeing Germans were encountered. General Fredericks and the FSSF (First Special Service Force) continued to display their competence in combat. At one point in the advance, General Fredericks was riding a horse. He would act as “point man” and make enemy contact . Whereupon, his troops would proceed to rescue their commander and rout the Germans. The rest of the Rome campaign is well documented elsewhere.

Immediately after the capture of Rome, The 463rd was bivouacked in a monastery overlooking Lake Albano. This is when the reconstitution of C and D batteries occurred. The new batteries were assigned a cadre from the current organization plus 100 recruits from the Basic Infantry Replacement Training Corps with a small number from other branches. With less than 6 weeks to train for the Southern France invasion, an intensive training period was implemented to make artillerymen and local security personnel (antitank and antiaircraft) combat-ready .These personnel were quite adept in reaching an acceptable level of competence as the units evolved and as combat activity would demonstrate. A credit to all involved in the challenge.

D Battery's mission in Operation Dragoon was local security. The artillery pieces were loaded on gliders at Follonica and were never recovered by the 463rd... So D continued it's original mission until later. I dropped with the group that landed in the Le Muy area. Before we boarded the planes, we had been given 2 pills ( amytal - a short-acting sedative and scopolamine an anti-emetic) to prevent air-sickness. While there was no sickness in my plane there was drowsiness. I recall the crew chief notifying me (the jumpmaster) that we were 15 miles from the DZ and the red light was on. The next thing I remember the soldier next to me nudged me and said “Lieutenant, that light is still on”. Whereupon I jumped up and proceeded to prepare for the jump. It was very exacting ensuring everyone was properly hooked up and prepared for exit in the darkness. When I looked out the door as I waited for the green light, I noticed red lights outside the plane. I'm not sure whether it was flak or exhaust from the airplane. All it did was make me glad we're going to get out of that plane, shortly.

For a number of days before the jump, we had studied a sand table model of the DZ area. Needless to say, I was diligent in my study. I noted a river south of the DZ... I had water landing training, so, I was prepared to avoid drowning on landing (I was a good swimmer and I had a life vest). The plane did not slow very much before exit, so, we had plenty of time to prepare for landing. As we descended I heard what I perceived to be water and was prepared for a water landing. About this time Mother Earth bumped me in the rear end as I made a soft landing. What I was hearing turned out to be soldiers crashing into trees. And I was in a small clearing.

Unfortunately, some of the equipment had landed in a ravine and it was impressive to see gun crews, with expletive exhorting by gunnery Sergeants, muscle guns up inclines to level ground positions. As we assembled and organized, I recall passing a soldier from my battery asleep at the roadside (I presume from the “puke medicine”). I kicked him in the foot and said “get up soldier ! There's a war on”.

It was several days before the D battery contingent which had landed in the south arrived with a story of fun surprising the Germans and having one company of the enemy, with a Captain in the lead, surrender and announce that they had been waiting for the invasion. An indication of the morale among some of our enemy.

After he Southern France invasion and the adventurous operation in the Maritime Alps the next operation followed in the French Rivera at the Italian border in a defensive mode with minimal activity. Then the organization moved to Mourmelon by truck and train (40 and 8 type box cars). Typical French speed. The train would stop, intermittently, and the engineers would be picking grapes in a vineyard adjacent to the tracks or some such thing, which enabled us to dismount and stretch a little.

Arriving in Mourmelon, we were bivouacked in the same area as the 101st. Shortly, I would learn that we happened to be in the right place to be attached to the 101st for another “Rendevous with Destiny”. On the evening of December 18th, We had barely settled into our bivouac area. I voluntarily assumed the duty of OG. When I eventually went to bed the phone rang before I finished my night prayers. It was Headquarters notifying me I was to report to the CP. Thus began, the rapid preparation for a trip to Werbomont, Belgium. Our destination would change enroute. It was well after dark when our convoy of A battery and D Battery got underway. A company of Quartermaster trucks were to transport us.

Needless to say, the truck drivers were apprehensive, having never been exposed to combat conditions. I rode in the lead truck of the D Battery column which was one of ours with our driver. Our map showed a fork in the road up ahead. I naively assumed the A Battery column ahead of us was aware and would make the proper move at the intersection. I was dozing when my driver suggested that we were in trouble. The column was stopped. I dismounted and looked around; then walked to the head of the column and talked to the Lieutenant (who will remain nameless) in the lead Jeep.

We agreed we had missed the turn after he drove several miles up the road and found no intersection. We made the decision to turn the column around. With the wet terrain this proved daunting. After several trucks became stuck in the muddy field and were winched back to the road, we placed a winch truck out in the field and laboriously winched the trucks, one by one, out to the winch truck and back to the highway. Finally, The last truck was back on the road, The roadside winch vehicle with front wheels in the ditch would not move. The driver insisted his front wheel drive was broken. I was suspicious and told one of the other Lieutenants to try it. He placed the front drive in gear and backed it out with no difficulty. The quartermaster driver was apparently nervous out of fear of what was ahead. We resumed our return to the proper intersection and continued our journey to Werbomont.

We stopped at the point where we had been instructed to proceed under blackout and checked to make sure we were all on the same page. I was very wary that we do it correctly. When we stopped I was in my Jeep now leading the convoy. My driver lit a Coleman stove and placed it on the hood of the Jeep. Before he could do anything else a tank destroyer came up headed in the opposite direction. The commander shouted “put out that light”. I approached him and told him what our orders were and he responded that things up ahead of us were changing rapidly and to beware. The stove was extinguished and we resumed the convoy. Shortly thereafter, we stopped behind a column of vehicles and found out our destination had changed. I'm not sure we knew exactly where it would be at that point. Soon after, with no further movement, daylight came and we were shrouded in dense fog. I was concerned about air attack on our bumper to bumper column. We discussed what we would do if such were to happen. Fortunately, the weather continued to protect us until later in the day when we arrived at Bastogne and took our battle positions.

Serendipitously, D Battery guns were emplaced in a box formation. This later allowed fire capability to any part of the perimeter of the “hole in the donut”. On Christmas Day, we were firing for effect with “ Division one round”, since all of our HE ammo was exhausted as was the rest of the artillery units. Meanwhile other units in the battalion had occupied previously designated positions to repulse armor. Their heroic accomplishments are documented in the history.

On the day after Christmas, General Patton's 4th Armored broke through the perimeter and Patton came by on his way to the front line. He stopped at our gun position. I reported to him and he asked for a telephone. I was able to direct him to my phone attached to a pine tree 3 paces to his right. He stated that he wanted to “get some Air on that sh.. that was coming in”. He jumped back into his Jeep and was off to the front. Shortly thereafter, 3 P-47s appeared above us. Before I could do anything beyond identification, an AA gun on the hill belonging to the adjacent artillery battalion fired at them. They promptly circled and deployed into dive-bombing configuration. At this point I phoned my AA guns and ordered them to fire at them because they were going to bomb us. After several bursts made contact the P-47's pulled up and decided to leave. The gun which attracted them from on the hill was silent during this. After I gave the fire order I ran to my personally dug trench and found it occupied by Lt. Whittington (who hadn't dug one) who refused to leave. By that time, the planes were leaving and I was giving the Lt. a piece of my mind.

The following day, General Taylor arrived fresh from his family Christmas visit in the US and inspected my battery position; which he proceeded to criticize.... “Why were the guns in this unusual position “? (box formation for 6400 mil field of fire) ”Why were men sleeping by the guns “? ( they were firing 24 hrs a day) ”Why didn't they have clean clothes”? (they're back in Mourmelon), etc, etc.... That evening we reconnoitered a new gun position and moved the next morning. While we were moving, General Patton was busy in front of us relieving three newly-arrived Infantry Regimental Commanders because they had not achieved their objectives by noon. An offensive had started that morning which placed our activities in rather bold comic relief. So much for satisfying General Taylor's abiding by the “book”. This was not the only incident I had with General Taylor. I have to wonder why a Field Commander would humiliate a battery commander, and his men who have been through more than a week of 24 hour combat under very adverse conditions and require them to change positions in the midst of an offensive. And within a couple of days of being relieved. I could imagine his having, inadvertently, missed his opportunity to write a heroic chapter in history by taking Christmas vacation might have entered into his demeanor; hardly consonant with the conduct of a brilliant field commander. I don't like to talk badly about a dead person, but, I hope for the opportunity to discuss this with him sometime, in a more spiritual setting. After these many thoughtful years, I have decided he lacked a characteristic of great leaders viz. “the common touch”.

General McAuliffe certainly displayed it at Bastogne. Early Christmas Eve we received a paper Christmas greeting from him followed by a personal visit to the fighting units under his command. When he came to D battery, and I reported to him, he returned my salute and proceeded to the gun positions and offered praise and words of encouragement and inspiration to the battered individuals manning the positions. A brilliant demonstration of “the common touch”. And we all know what happened the following day. General McAuliffe richly deserved the place he has received in history.

After our mission to Alsace, we were sent to Dusseldorf-Neuss area of Germany. I remember observing across the Rhine to Dusseldorf, where factories were still working. We had daily TOT (time on target) fire missions shortly after the noon whistle blew. Neuss had munitions factories untouched with only the main power switch destroyed. The residential areas were completely demolished except for a few apartment buildings. The allies were bombing the people late in the war, obviously. I recall seeing some children playing in the street and watching them scatter to shelter when they heard an airplane approach. A grim reminder of the horror of war and what it does to people.

When we left Neuss, we ended up on VE Day (my birthday) near Miesbach Germany, adjacent to the Autobahn. Part of the German army was marching up the highway 10 abreast with a General leading them and accompanied by a few American Jeeps on the way to Munich. We also went by a concentration camp with the newly released victims walking up the side of the highway. They were emaciated and barely able to wave at us as we passed. This sight really “grabbed” me; as I realized, THIS IS WHAT WE WERE FIGHTING FOR !!!!!!!!!

I still “tear up” when I recall that sight.

I received orders to turn in all ammunition at the dump in Munich. Accordingly I placed one of my Lieutenants in charge and sent the convoy on their way – he led the convoy in a Jeep. I gave him instructions to find overnight accommodations for the men and to return the following day. The bridges on the Autobahn had been demolished so the bypasses slowed travel. The following morning, when I went to breakfast, I saw all the convoy truck drivers. I asked why they were back so soon and they replied that they made such good time they turned around and returned. Typically, the type of Soldier we had in our outfit. They left the Lieutenant in their wake with their vehicles in 5th gear and avoided the opportunity to find trouble in Munich. Their opportunity for celebration would come later.

Several days later we embarked for what would be our respite from war. We arrived in Bad Reichenhall to find that our Air Corps had bombed the luxury hotel and the brewery. However, there was plenty of alcoholic beverage stashed in hospitals and other locations. This had been the Communication center for the entire German Army. There were large telephone cables coming into it from all over Europe, apparently. It was reported that 800 German WACS were there. When we arrived, all German forces had gone underground. We were forbidden to fraternize with them. The only female visitors to our Officers mess in the Cafe Reber were Army nurses.

D Battery was assigned a group of single story apartments and several houses. Within an hour of our arrival in the area, 1st Sergeant DeLisle informed me that we had just liberated 51 cases of cognac. This was French cognac with a Wehrmacht stamp on it it which meant it was “contraband”. I told him to be cautious how he allowed the men to deal with this. Realizing the war was over and filled with love and admiration for my brave and loyal men, I chose to leave it in their hands. There was a case of it under my bed when I retired that evening. Needless to say, the men proceeded to enjoy a celebration which continued in an orderly fashion due to the efforts of my non-commissioned officers. However, Col. Cooper became aware and was concerned that I should have taken control and offered it to the Officers' Club. (which had enough for our needs). This was a quasi-obsession with Col. Cooper. Practically every morning, at breakfast, he would tell me a story of encountering a drunken soldier who said he got the booze from D Battery. The obsession ended when he inspected our battery area and found a ½ bottle of cognac. (he had warned of the inspection the day before; so everything else went underground).

In July, those of us who were going home were transferred to the 17th Airborne. I became a temporary Regimental Executive Officer under Colonel Nelson. This was a critical time for the soldiers who, now, had nothing to do. I recall one soldier who stole a Jeep and went AWOL. Several days later his remains were returned to us in a body bag. He had been drunk and had a fatal Jeep accident. When the Adjutant asked me what to note in the morning report, I had to tell him the status was still AWOL. I felt sorry for his family because I wasn't sure how this would affect his veterans' benefits and his discharge. One of the bad feeling incidents of my time in the service. My worst emotional experience was packing Charlie Derby's personal belongings after he was killed in Sicily. He and I were very close during training and had motorcycles at Fort Bragg – much to the chagrin of Colonel Harden who had a dislike for them for some unknown reason. The day before we left for overseas, he delighted in informing us to “dispose of them by 1500 hrs today”. We had previously arranged to have them shipped home and took them to the motorcycle shop in Fayetteville.

After the war, I had occasion to visit the Derby family in Worcester, MA, which was an emotional and mutually satisfying experience. I could envision my family in such a situation; another reminder of my good fortune. Thanks God !

In September '45 I journeyed from Marseille to Boston to Fort Dix, New Jersey and was discharged. I returned to my family in Rochester, N.Y. I was the first child out of the service. My 4 brothers (1 in the Army, 1 in the Navy and 2 Marines) had not returned from overseas service at the time. I lived with my parents and returned to St. Bonaventure College as a graduate assistant while applying to medical school. I entered the University of Rochester Medical School in 1946.

After arriving home in 1945, I became romantically involved with an earlier acquaintance and we married just before my second year. When I finished medical school and postgraduate training in 1951, we returned to Rochester, N.Y. With 2 sons. I joined the medical staff at St. Mary's hospital where I had gained my inspiration to become a physician. Soon after, I became Head of the Department of Anesthesiology and developed the new Department, served as President of the Medical Staff and spent the rest of my professional career there dedicated to continuation of the fine patient care I had received years earlier. I ,also, found time to participate in multiple medical organizations. Our 3rd child (a girl) arrived shortly after I entered practice.

I look back on my Army Service with gratitude for survival and many lessons of life learned. One might say, I achieved maturity very rapidly. I would have no qualms about doing it all again. It was a blessing and I have never regretted any of it except for the loss of some dear friends; most especially Charlie Derby.

Right after the war, a few of the northeastern folks started meeting once a year at someone's home for a long weekend. Eventually, these reunions developed into larger gatherings at Airborne reunions and meetings and have continued for some 60 years. Currently, our ranks are dwindling and our reunion days are numbered.

We have been blessed to have a number of Belgian citizens who have continued to memorialize the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion in many ways. Filip Willems, Webmaster of the 463rd website, is one of many Citizens of the Bastogne area who refuse to forget the noble efforts of The US Armed Forces in stopping the German War Machine.

I think the legacy of World War II which cannot be forgotten; despite revisionist historians, is: WHEN FORCES OF EVIL ATTACK THE UNITED STATES, EVERY CITIZEN SHALL MOBILIZE AND NEUTRALIZE THOSE FORCES WITH THE BLESSING OF GOD AND THE WILL OF THE PEOPLE !!!!!!!!

Hopefully, the Veterans' Organizations will ensure this part of our history is not distorted or forgotten and will ensure history curricula in our schools maintain it's inclusion.

GOD BLESS AMERICA ! AIRBORNE ALL THE WAY !