Trooper S/Sgt Roy Lynwood Montague, Jr.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 30, 1917 - December 3, 1975

By: Monty's Children and Grandchildren

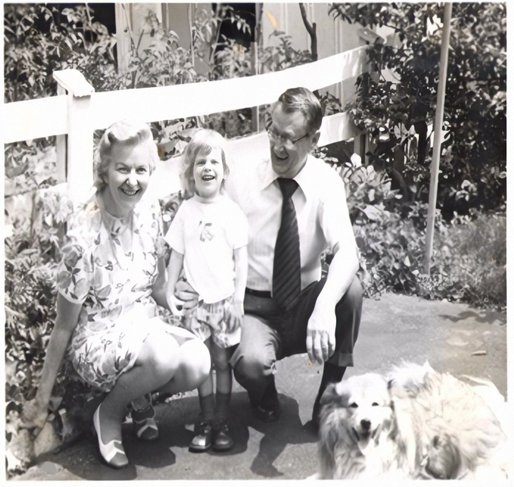

Mother, first grandchild Robert S. Gray, Dad, 1974

INTRODUCTION

Like many other soldiers, Dad shared little with us, his children, about his time in World War II. As his children, we knew little more than that he'd been a paratrooper with the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, and that he'd met our mother while he was stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. However, he did speak one evening in 1966, when he took the youngest of us, 10-year-old Jeff, to see Henry Fonda in the newly-released Battle of the Bulge.

Noting the historical inaccuracies, Dad also whispered his reflections on the real battle, the one he'd fought and survived. Most poignant was this: “I was proud to serve and do my duty, but I wasn’t proud of some of the things I had to do."

After Dad's death in 1975, Mother shared a box of letters he'd written her, from the day they'd met in March, 1943, through his discharge in 1945, until nearly the day of their wedding.

Only then did we form a clear picture of his early life and service. While those letters tell the story of a long-distance courtship, they also provide a chronology of the 456th and 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalions (PFAB). In addition, we've found photographs, most of them, as we've learned from Filip Willems Fire Mission! Battery Adjust!, taken by his friend Cpl. Anthony Spagnol. Also, we've got Dad’s original orders, citations, service medals, and jump maps on paper and silk. Together, they're the contents of a time capsule for the father we lost nearly 50-years ago, and for the Pop-pop of 10 grandchildren, only one of whom he ever knew. We hope the quotations below, from Dad's letters, will be a posthumous interview, and will honor the humble, loving man we still call Dad.

PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA: Early Life, 1917--1941

The middle child of three, Dad was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 30, 1917, and raised in West Philadelphia. Throughout his life, he remained close to his parents, and to his two sisters and their families. He attended B. B. Comegys Elementary School, and West Philadelphia High. He enjoyed basketball, swimming, and horseback riding. Boy Scouts was in its infancy when Dad earned the rank of Eagle Scout, honing his skills in cooking, hiking, orientation, and camping.

From 1934 to 1936, starting when he was a senior in high school, he worked as a Truck Helper on a laundry delivery truck for the Service Laundry Company. During all that time, and until he began basic training, Dad and his family regularly attended services at the Fourth Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia, within walking distance of their row-house; and, they took part in many of its organizations.

In the years after graduating in 1935, and because his father's salary from the Pennsylvania Railroad would not support Dad's dream of attending Drexel Institute of Technology, he enrolled in night-classes, some at the University of Pennsylvania, others at Temple University and at Drexel. During the day, from 1936 until 1940, he was employed as an Assembly Mechanic at the Westinghouse toaster facility; and then, from 1940 to 1941, at another Westinghouse plant, as a Turbine Operator.

During his leisure time, Dad enjoyed riding horses in Philadelphia's Pennypack Park, and swimming at a public pool on Baltimore Pike, in Springfield, Delaware County, a long bus-ride west of his home, and a short walk from where he and Mother later raised the four of us. On October 16, 1940, Dad registered with the Selective Service.

Even today, though we know little more than that, it's easy to see Dad as a devout, active, energetic, and ambitious young man, unaware of the dangers he was soon to face, but preparing for them nonetheless.

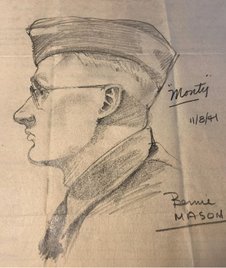

November 8, 1941

Fort Belvoir: Roy L. Montague, Sr. (Dad's father), Dad, Willa Cook Montague (Dad's mother)

In January, 1942, Dad was transferred to the 20th Engineers, stationed at Fort Blanding, Stark, Florida, where he was promoted to the rank of corporal and served as a light-duty truck driver. Four months later, on May 5, he was transferred back to Fort Belvoir, to Engineers Officer Training School (EOTS).

On October 29, 1941, Dad was inducted into the army at Fort Meade, Maryland.

The next day, he began Basic Training at the Engineering Replacement Training Center, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, as a member of Company A, 5th Engineers.

SOUTHERN STATES:

Induction, Early Days, October 29, 1941--January 2, 1943

Dad at Jump School, January 1943

His "Separation from Service Record" indicates that, sometime in the next month, he was assigned to the 1st Engineers, Company 2, promoted to the rank of sergeant, and began working as a small arms instructor. Thereafter, Dad's disposition within EOTS is unclear. However, with another path apparently in mind, he requested a transfer to the airborne.

On November 26, 1942, two years after his induction, Dad was ordered to report to Parachute School, at Fort Benning, Georgia. There, he resumed the rank of private, and, on November 30, began the four-week jump school. (We have an original, 3" x 8" booklet about the school's program, with photos of the men in training.)

October 29, 1941, Dad was inducted into the army at Fort Meade, Maryland.

Did Dad know then that, just weeks before, on November 8, Operation Torch had begun, the invasion of North Africa? As the first large-scale deployment of American paratroops, it would drive Germany from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, opening those countries as areas for training and staging grounds, before the Allies' invasion of Europe. Did Dad know that he'd soon be there in the sand and heat? On January 2, 1943, Dad received his wings; and, as a member of the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion (PFAB), Able Battery, he headed to Fort Bragg, where he fell in love.

FORT BRAGG, NORTH CAROLINA:

Preparation for War, January 2--April 20, 1943

In late February, 1943, at a dance on base sponsored by the USO, Dad met a young belle from the next-door town of Raeford, then living in Raleigh, Mary Shaw McDiarmid.

March 22, Letter to his sister Ann: “I've been to Raleigh a couple of times to see a girl I met. She's been down here to 2 dances, too. I hope to go up tonight.”

In the next six weeks, the two enjoyed a handful of double dates, at dances on base, and on visits to her. Photographs show them clearly happy, some with friends like fellow troopers from the 456th Private Larry Sporbert and Heidi (last name unknown). Dad was smitten; she, not so much. In fact, before he left the States, although Mother reluctantly agreed to accept his jump wings, she also stipulated under what conditions she was doing so. She had already been honest about dating a fellow from the Air Corps, and now suggested she and “Monty” remain just friends.

From those first days and until his discharge in 1945, Dad wrote Mother 150 letters. After that, while he and Mother planned their wedding, Dad wrote another 101.

Because the censors blackened and cut out much of the wartime letters, including V-mail--those letters that were photographed and reduced in size--most refer only vaguely to places and events. Subsequent letters clarify some of the vague references; and, thanks in large part to Willems' book and to his website on the 463rd, we've since learned much more.

March 22, Boots and buttons: "Our battery has been picked to fire a 21-gun salute tomorrow for some General and at present all the boys are busy shining boots and buttons."

April 19, Shedding tears: "Yesterday I spent working at a gas chamber. We put quite a few hundred men through a chamber containing tear gas. It was to test all the gas masks and give the men faith in their masks. I was thoroughly saturated with the blame stuff and am still shedding tears."

On April 20, 1943, the 456th headed to Cape Cod, and then to Staten Island, to make the 12-day voyage to North Africa.

April 22, My ghost: “You needn’t worry about seeing my ghost at the dance this week. I'm quite a little distance away on a train.”

Dad, Mary Shaw McDiarmid

NORTH AFRICA: Acclimatization, Training, Staging, May 11--July 9, 1943

Six months after starting Parachute School at Fort Benning, Dad landed in Morocco, once again as a corporal.

Soon thereafter, near Oujda, close to the Algerian boarder, he began training.

May 11, Ant colony: "After debarking, we marched about five miles to our present encampment. There is row after row of tents. It looks like an ant colony."

May 16, On a plateau: "We made another move, fairly long, in a horse car with 30 others. We're now on a plateau, from which only the peaks of these North African mountains (high hills) can be seen, sleeping in pup tents on a plateau overlooking mountains."

May 30, Sick: "Today was my birthday. I celebrated it by being sick all day. The weather is very hot. It must be up around 120 during the day. My buddies from Ft Bragg are both sick in the field hospital with dysentery and heat stroke.”

June 8, Whirlwinds: “Quite often we have whirlwinds that raise big columns of dust. Yesterday one came right down a line of tents. One fellow’s tent was picked up from around him and there he sat looking so doggone funny and we all got pains laughing so hard.”

June 13, High dive: "Remember in my last letter I said we had another high dive coming up? Well, we made it last night, and it went off quite well [censored]. It was wash day for me. I got me a helmet, soap, and water and scrubbed. I also attended a Memorial service for a man killed in an accident; he went out just the way none of us want to."

A passage in Mitchell Yockelson's The Paratrooper Generals explains that, during that night-time high dive, a crew chief was accidentally pulled out the door--without a chute. Soon after, protocol was changed, requiring each crew chief to wear one.

Also in June, Private Anthony Spagnol and his camera joined A Battery. Dad’s letters mention having no camera himself, yet he returned from the war with lots of pictures. For years, we wondered who took them. Spagnol kept an invaluable diary, too, in which he mentions having his film developed at shops in towns the Allies had secured, and then sells prints to fellow troopers. The diary of the next two years shows that the two men found a welcome comradery, especially later during the campaign in the Maritime Alps.

June 16, Last chance to write: "Although there is very little about which I can write, I'll write anyway, for I feel the need of your company. ... It's quite possible this may be my last chance to write for quite a while. We came over for a purpose and we will be used for it."

As part of the invasion of Sicily, the 456th was soon to make its first combat jump, during which Dad’s official duty classification in A Battery was “Scout."

SICILY: Operation Husky, July 9--August 17, 1943

After six weeks of training in Morocco, the troops were flown six-hours to an airbase near Kairouan, Tunisia. From there, in the late-night hours of July 9--10, they flew the short distance towards a jump zone near Gela, Sicily, each plane carrying a stick of 16 paratroopers. High winds blew many planes off course. Nevertheless, at 12:45 am,

A Battery jumped.

Operation Husky, the joint American--British air and sea invasion of Sicily, drove Axis air, land and naval forces from the island; for the first time since 1941, opened the Mediterranean to Allied merchant ships; diverted 1/5 of Hitler's forces from the eastern front; led to the toppling, on July 25, of Italian dictator Mussolini; and, on September 3, allowed the Allies to invade Italy.

On July 10, Dad was at Biazza Ridge when the 456th knocked out several tanks, repelling an attack by Germany's Hermann Goering 10th Panzer Division. On July 13, still on the Ridge, Dad was wounded by shrapnel in both his left leg and left arm. He was evacuated by train and ship to an operations-base field-hospital back in Tunisia.

July 26, Mistaken: Dad's dry sense of humor had not deserted him. "Since my last writing I've been moved to another hospital. While on a French hospital train I was mistaken for a German prisoner and on an English hospital ship coming back to N. Africa I was mistaken for an Italian prisoner."

August 1, Peep-peep: "The scenery right here at the station hospital is quite pretty. We are on the floor of a small valley, closely surrounded by very rugged hills, some of which are covered by the stubble of cut wheat. Occasionally across the valley a train may be seen with its 1880 model-cars and peep-peep of a whistle."

August 9, Sweat and blood: "I would give an arm and a leg to be finished with this business. It would be so good to know that a return trip was assured. But Shawnee, it isn't death I'm afraid of, for I can't come closer to that than I have already. It's that there is so much worthwhile living for. ... But this war--it's so dirty, so nasty, so senseless. Oh, I know it has to be finished, we must win, and we will, not by wishful thinking but by sweat and blood, that of my buddies. ... Even now I suppose I could get out of combat duty by complaining of a bad leg. ... But if I knew I should die ten times over I shouldn't be able to do that. If I were like that, I'd still be home working at my defense job [at Westinghouse]. That also means I'd never have met you."

August 17, Scrap drive: "Being still in the hospital, I've had no word from the outfit. Yesterday I went under the knife again. Does that sound impressive? We found another piece of shell, close to the skin, on my arm. ... This piece was quite small. The one taken out in Sicily was one inch by two. So that only leaves about six pieces in me. I'm rather concerned about returning to the States. Some patriotic soul might turn me in to the scrap drive."

August 27, Hillbilly music: Finally discharged from the hospital, he headed by train to a replacement center, accompanied by English soldiers, one of whom had a guitar. "Sometime when you're in need of a laugh just listen to an Englishman singing hillbilly music."

On August 31, seven weeks after being wounded, Dad was reunited with his unit at a base camp and training ground in Bizzerte, on the northeast tip of Tunisia.

ITALY: Invasion, September 3, 1943--January 31, 1944

When Allied Forces invaded Italy, they did so without the 456th. Instead, during September, the unit continued to train, primarily in Comiso, Sicily and in North Africa, shuttling back and forth. On October 1, the 456th began a circuitous journey, by train to the Sicilian coast, by ship to Algeria, then by truck to Bizerte, where they continued training. Finally, they boarded another ship, the Anson Jones, and sailed to Naples, which the Allies had seized back in September, arriving on November 30.

October 9, False teeth: On Sicily, while preparing for the invasion of Italy, Dad wrote, "I had a lovely trip to the dentist again the other day. About a 140-mile round trip. ... The dentist drills until you're dizzy, he chisels, cuts your lips, gives you a headache--for what? Eventually you lose your teeth anyway and get false ones."

October 10, Accommodations: "We've got twin beds, ants, canvas roof (maybe it won't leak), flies, a door thru which only contortionists may enter, worms, electric lights (flashlight), spiders (I just killed a one incher), running water (when it rains), and lots of fresh air."

Hustled onto a ship: While discussing the content of this Trooper's Page, our older brother, Lyn, remembered perhaps the only story that Dad ever shared with him, about an event that must have taken place at about this time. “When I was in North Africa, I was awakened one night and hustled onto a ship for Sicily. Turns out I was being sent to pick up long-johns!” Acquiring a supply of winter long-johns in North Africa must have seemed like a SNAFU. Later, in the Italian mountains, bet he was glad.

October 18, Wasted hours: Dad described a Sicilian sunset, and then pondered, “With so many pretty things in life to enjoy, even something so simple as a sunset, you wonder why people have to have wars. Life is too short to have to spend wasted hours away from the folks we love."

October 22, Your dark glasses: "Our good friend the medical Sgt., Doc Moore, is no longer in a class by himself when it comes to ribbons. I've got a few myself and I'm not home yet. So, you'd better get out your dark glasses and be ready for the time when I flash those ribbons."

October 26, The problem: In an atypical vein, “Well, the chances are about one out of two the problem [that is, the status of their relationship] will be automatically solved within the next year. So don't bother too much about it. It was almost solved once." [By his wounding at Biazza Ridge]

November 21, On the move: "I guess you are wondering why I haven't written. My excuse is good, but not printable. And it has nothing to do with the lovelies in Naples. We can't write and be on the move both."

On November 30, the 456th entered the Italian Campaign. From Naples, they headed northwest into the mountains, as the supporting artillery unit for the joint American--Canadian First Special Services Force (FSSF). Together, they fought in battles such as those at Monte Sambucaro and Monte Cassino. Throughout, Dad served as the battery's scout in a communications unit.

December 29, Galoshes: "As for Christmas, let's start hoping I'll make it for '44. ... Uncle Sam didn't get out that Xmas dinner to us, but he gave us another present--more winter clothes, and a great big pair of galoshes."

January 28, Repairing a break: Southeast of Cassino, on the outskirts of San Vittore, Dad provided a glimpse into one of his tasks: "What a sensation it is to be sitting in a 15- or 20-minute old shell-hole repairing a break in the communications wire, wondering where the next shell will land."

A few days later, by vehicle and on foot, the battalion reached the port town Pozzuoli, and headed from the frying pan into the fire.

ANZIO: Operation Shingle, "The Meat Grinder," January 31--May 23, 1944

ROME: Liberation, May 23--June 4, 1944

Back on January 22, the first day of Operation Shingle, although the Allies had massed 36,000 troops on the shore, and 3,200 vehicles, instead of pushing forward, they stayed put, to maintain superiority. Doing so, however, allowed the Germans to strengthen their positions on the surrounding high ground.

Now, on January 31, at Pozzuoli, the 456th and the FSSF climbed aboard landing craft and headed 100 miles up the coast, debarking two-days later on the beach. Under the unrelenting attacks that continued until their breakout from the beachhead in May, they dug slit trenches and clambered in.

On February 6, when a direct hit on the Battalion Command Post killed and wounded numerous officers, Lt. Col. Cooper directed a hasty reorganization, replacing them with competent NCOs from the batteries. Dad was one of them.

On February 20, the 336 officers and men of three units of the 456th (Headquarters, and A and B Batteries), were officially designated as the 463rd PFAB, and removed from the 82nd Airborne Division. Codenamed "Keynote," this "bastard battalion" provided artillery support for various elite infantry units at Anzio, including the FSSF, the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, and the 550th Airborne Infantry Battalion. Later, they provided the same support in southern France, again to the FSSF.

February 22, Morale booster: “Now doing Fire Direction. It's a morale-booster having a direct hand in laying fire on enemy personnel, tanks, vehicles, etc." The return address uses the new battalion's designation of the 463rd.

February 22 (from the same letter), Candles: “For 3 weeks I’ve been working with HDQ’s Btry. We were in an area surrounded by [our] large caliber guns. At night when they were fired, if we had candles lit in our tents the concussion from the muzzle blast would blow them out."

February 26, An egg with a shell: “The group I am working with, including officers, are all at least a year younger than I; I've been dubbed with the nickname of ‘Pop’. Up here ... good food is not too plentiful. Haven’t seen an egg with a shell on it for some weeks.”

March 3, Muddy: “I was taking a helmet bath when shelled; my option was to jump into a muddy fox hole.”

April 9, Fireworks: “Over here we have fireworks every night when big guns are fired. The entire sky is lit up, planes drop flares, ammunition burns, and so forth. But the prettiest sight of all is a mass anti-aircraft barrage; tracers cross paths from many, many guns which steadily mount higher, forming an immense fishnet of crimson. Larger X shells are fired which burst at tall heights with a brilliant flash creating hundreds of hitherto undiscovered stars. Occasionally an invisible plane will let go of bursts of machine-gun bullets that, in the darkness of night, appear to be a monster stinger lashing out. Say, that sounds as though I enjoy these air raids and that, I maintain, is impossible!"

May 14, Chow wagons: "I personally worry more about the safety of our chow wagon than anything else."

May 17, Household visitors: "Mice, ants, mosquitoes, and insects of all types and breeds have kept us company in our foxholes. The latest household visitors are snakes."

On May 23, the 463rd left Anzio, heading up Highway 6 towards Rome, which was liberated on June 4. Those men, among the first to enter the city, had been fighting towards Rome for 166 consecutive days. For the 463rd, the liberation marked the end of fighting in the Italian Campaign, and time for rest and recreation.

June 10, Resting on Lake Albano: Dad described the old monastery where they were staying, and commented, "Keeping the Jerries on the run wasn't too much fun. Although now that we have been relieved for a spell, I can see where there is some satisfaction in feeding lead to them. I was in Rome for a short stay. The outfit is now resting, something we have looked forward to for almost half a year. ... Eat much, sleep much, fatten up for the next round, them's my intentions."

On July 15, the 463rd moved to the coastal town of Lido de Roma, a summer resort for the wealthy. Without the C and D batteries of the 456th, who had now gone with the 82nd to train for Normandy, the 463rd needed replacements to bring it up to full strength. When replacements arrived, preparation and training began for the next combat jump.

In early August, Dad received a jump-step promotion, from corporal to staff sergeant. (Though he wrote the new rank in his return address, he never mentioned it in the letters themselves.) As a communications chief, he now oversaw a 25-man section as they installed and operated the wire and radio facilities of a firing battery, and he supervised the battery's instrument and fire control.

SOUTHERN FRANCE: Operation Dragoon, August 15--September 14, 1944

On August 15, the 463rd left Grosseto, 100 miles north of Rome, as part of a massive invasion, that included 535 aircraft--C-47s and C-53s, towing 465 Gliders. By opening another front, they aimed to press German forces, and to seize ports on the French Mediterranean.

At 4:25 am, Dad's A Battery jumped near Le Muy.

August 24, A Frenchman found us: "I jumped in S. France, landing in the mountains, coming down thru' dense trees to hit a very steep slope. After finally getting out of my harness I found one other man from our plane. By the next evening five of us had gotten together. We were washing in a stream when a Frenchman found us. He fed us and then the next day set us on the route to where our outfit was. We joined them and things are rolling along fair."

Until August 30, Dad and Corporal Spagnol guarded the forward observation post and its radioman in a house in La Napoule. Neighbors cooked their meals; and, a German combat patrol surrendered to them, giving up guns, ammunition, and intelligence about two other targets.

FRENCH MARITIME ALPS: "Champagne Campaign," August 30--December 12, 1944

Dad in the French Maritime Alps

On August 30th, the 463rd began to move its 450 men and equipment by truck, 200 miles northwest over a zig-zag Alpine route. Not far from the Italian border, the men assumed positions, and fought as mountain troops for the next seven weeks. During those weeks, the "Champagne Campaign" entailed combat, of course, but combat interspersed with passes to the French Riviera.

September 4, A fellow's appetite: "I'm glad to say things could be a lot worse for us here than they have been. They'll be the best of course when Jerry has been licked and has quit. Just one or two close shells are rough on a fellow's appetite."

September 5, 1944, From Corporal Spagnol's diary: "We were shipped to the mountain area near Barcelonnette and Jausiers, France. Our OP was at an old fort called Restefond, about 9000 ft, at the top of a mountain which gave a scenery sight which seemed to be on top of the world. On our few days off S/Sgt RLM and I became very friendly with a Jewish family in Barcelonnette. I took pictures of the family and their home. We gave them soap, toilet paper and other items which were in very short supply in France."

September 15, He might get hurt: During these weeks, Dad must have been growing discouraged again about his future, for he wrote a letter explaining why his writing had slowed. In the only reply of hers that survives, written on September 15, 1944, Mother gently confronted his tone, reminding him that, at Fort Bragg, she had expressed her concern that he might “get hurt” if her feelings did not develop as he hoped. Even so, other letters were apparently in transit, which must, in fact, have encouraged him.

September 24, A cross word: "That [last] letter should not have been written. ... your recent letters have been too different, too promising. So I'll trust in your generosity in overlooking a cross word now and then."

October 6, Best to move: "I've made it a practice since coming overseas not to stay in any one position too long. I think it best to move every so often, say two or three times a week, or even twice a day."

On October 8, the weather turned bad. At 10,000 feet above sea level, A Battery woke up one morning after a three-day blizzard, to find their guns under eight feet of snow. It was three days before snow plows could clear a road to them. When it was time to move, the battery fashioned sleds from corrugated roofs, and pulled all their equipment down to lower levels, the gun crews and chiefs of sections showing great initiative. (Dad always enjoyed taking us kids sledding. Maybe this is why!)

Dad (back row, 2nd from the left), Cpl. Spagnol (back row,

4th from left), unidentified French family.

The father took the picture.

On October 22, with the onset of winter, the 463rd was replaced by another parachute field artillery battalion, and was returned by truck to the south coast, to Menton.

A few days later, the 463rd headed back into the mountains, to Castillon, and were once again assigned to support the FSSF. "Old friends from Italy had rejoined to support with fire the final Force action. The artillerymen from the 463rd were still around, the men who had become Forcemen, for all practical purposes." (William B. Breuer, Operation Dragoon)

November 2, Pants down? "No sooner did I get set up to write tonight, and it's quite a set-up, than I had to go out in the mud to visit each man in my section, to find out his shoe size. We are having a 'weather' boot issued, for winter season. This is being written from within my most recent fox-hole. It's the width of my bed-sack, the length of my body, and high enough to sit upright in. The sides are lined with sand-bags; the top is a pup-tent. During the worst rain of the day I got caught with my pants down. I should say with my pup-tent-roof off. And that was strictly no good."

November 15, Monte Carlo: "Pardon me while I chew on a Hershey's Tropical Chocolate Bar, Army issue, made to withstand the weather. Soldiers are made to withstand such things as Army chocolate bars. I think the thing that sets these particular bars in a class of their own is the oat flour and vitamin B1."

Later that month, the 463rd gave support to the FSSF during their last major push on the French--Italian boarder, after which they were relieved. They headed to Camp Mourmelon in Northern France, for rest, resupply, and reassignment to the 17th Airborne Division (ABD). Traveling first by truck and then by railroad cattle-car, they arrived on December 12.

However, they received neither rest nor reassignment, for the Battle of the Bulge erupted.

BELGIUM

Battle of the Bulge: December 16, 1944--February 27, 1945

Siege of Bastogne: December 20--27, 1944

By early December, the Allied Forces in the European Theater had made great progress: they had pushed the Axis out of North Africa, Sicily, and southern Italy, and had defeated them at Normandy, in Holland, and in southern France. Now, Hitler was adamant: in order to turn the tide, Germany must break through the Allied lines in the Belgian Ardennes, and take control of the six roads that converged at Bastogne, so it could reach and seize the harbor at Antwerp.

The Battle of the Bulge would be Hitler's last stand.

At Camp Mourmelon, the still-unattached Bastard Battalion was temporarily assigned to the 101st ABD for administration and rations only, and, later that month, was to be permanently assigned to the 17th ABD. That never happened.

On December 17, when General McAuliffe ordered the 101st to prepare to defend Bastogne, Col. Cooper offered the already well-supplied and self-transporting 463rd, saying they could be ready in 45 minutes. Although ready, their position in the convoy didn’t open until 9:30 pm the next evening. When the 463rd finally did move out, they had a cold, wet, 12-hour ride, before the they entrenched their four batteries at the village of Hemroulle, 2 m/3.1km from Bastogne, "a dirt road, a village square, a watering trough, 20-odd homes, a church." (Hanlon)

Their defense of the village is legendary.

December 29, Hot Christmas: “As things are now I haven't but very little equipment with me--no old letters. And of course, my usually "perfect" memory has to fail me. Did you have a good Christmas? Don't forget to tell me how you spent it. Mine was cold in some respects and extremely hot in others. There is so little I can write of at present I shan't even try to write an interesting letter this time. As soon as I have a bit more leisure, whenever that will be, I'll write again."

January 8, 1945, Gettysburg: "The clipping I'm enclosing is my main reason for writing this evening. Do you remember when I was a member of the "All American Div"? Times have changed, haven't they? I always manage, I'm sorry to say, to be in the hot spots." The clipping, from Stars and Stripes” is entitled "Bastogne--a '44 Gettysburg" and is still attached to the letter.

On January 8, for leadership as a Forward Observer, Dad received the Meritorious Service Award from General Maxwell Taylor.

January 26, Grand time: "The days have been so full since I last wrote. I'm really sorry about not writing so often as I should, but the past month and a half have been more hectic than I like, too. Anyway, this [stationery] is German which I got while up in Bastogne with the 101st Airborne Div. Did you read about the grand time we had Xmas?"

Corporal Spagnol’s diary from this time makes clear that he and Dad were frequently together, just as they had been in the Maritime Alps. Spagnol sometimes formally refers to Dad, his superior officer, as "S/Sgt RLM" and, at other times, simply as "Monty."

February 14, Picnic: “Thanks for the valentine and photographs. In a way I wish you were here today, although I just finished digging a new hole. Rifle and machine gun fire, shell fire, planes, all can be heard, it's almost like being on a picnic today."

February 21, Paris: "You asked why I had been prevented from visiting Paris. I visited Bastogne--lovely place--instead."

On February 27, the 463rd was transported by truck and train back to Camp Mourmelon, for rest and resupply. At Mourmelon, they were assigned permanently to the 101st, the Screaming Eagles.

Rest, however, was not in the cards.

GERMANY: Operation Varsity, March 24 & 25, 1945

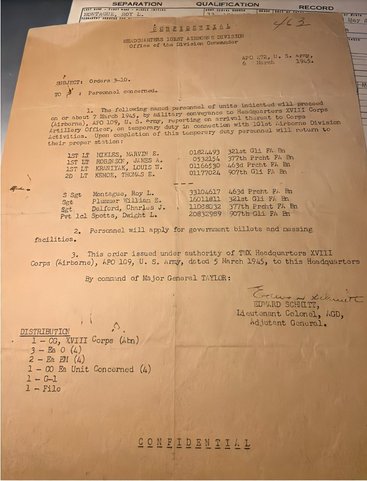

On March 6, Dad was ordered to "proceed on or about 7 March 1945, by military conveyance to Headquarters XVIII Corps (Airborne), ... on temporary duty in connection with the 101st Airborne Division Activities. Upon completion of this temporary duty personnel will return to their proper station: ... By command of Major General TAYLOR.” He didn't know that "Activities" meant Operation Varsity. According to the original orders, pictured, a total of eight men stationed at Camp Mourmelon--four officers and four enlisted men--had been selected for a special mission. Only two were from the 463rd, Dad and one officer. All eight were either glider troopers or field artillery troopers, well-seasoned, capable leaders.

For two weeks, along with men of the 17th, those eight men trained elsewhere.

On March 15, General Eisenhower presented the 101st, including the 463rd, with the Presidential Unit Citation for their defense of Bastogne. The Presidential Citation had never previously been awarded to an entire Unit. Of course, Dad was not present.

March 22, Hottest spot: His letter of this date is no different in tone or content than most, and he didn't name his current location, but he did write this: “Look for the hottest spot and you'll probably find me there."

On March 24, the operation began with a combat jump into Wesel, Germany, 4,964 troopers taking part. They captured and held all of their objectives, most within just a few hours. On March 25, the eight men were flown back to Camp Mourmelon in Gen. Ridgeway’s personal C47.

March 29, Rough mission: “I was one of 6 or 8 men from the 101st who jumped into Germany with the 17th Airborne. This was the 1st combat jump for the 17th, my 3rd. ... Rough mission but I’ve gotten a 7-day furlough to England beginning April 2nd."

While most of the troopers who had left Fort Bragg in early 1943 now had two bronze stars on their jump wings, Dad had three. He never spoke about that distinction.

“I just did what had to be done.”

A few days later, the 463rd left Camp Mourmelon for Germany. There would be no more combat jumps for the battalion.

Nor would there yet be that promised furlough.

GERMANY: Campaign and Occupation, April 3--early July, 1945

After a 14-hour journey by truck, on April 3, the 463rd arrived near Neusserweyhe, Germany, with the mission of directing support artillery for the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, and guarding against a German attack.

April 4, Non-fraternization: "Just like I said, my next letter would be written from England. So here I am in Jerry-land. ... Non-fraternization is strictly enforced. ...

Finally, on April 11, Dad began his furlough to England, for three whole weeks.

May 3, Afraid: Just prior to returning from England to his Battalion in Germany, Dad expressed this sentiment, often experienced--but less often expressed--by veterans of long-term deployments: “After such a long time of sweating and waiting it seems impossible that peace is expected momentarily. As much as I want to, I'm afraid of coming home."

For much of May and June, the 463rd worked as military police in the city of Bad Reichenhall. In late May, Dad visited the mountain town of Berchtesgaden, and walked through the remains of Hitler’s personal compound, Eagle's Nest.

June 20, Save that vacation: "Here is what I know [about coming home]. In one or two weeks those of us who are to be sent home for a discharge, and I am one, will be transferred to another battalion. With that outfit we will make the trip to good old U.S. It is my belief that the end of August should see us donning the civvies, I hope. ... So if you will, save that vacation a little longer. I want very much to spend it with you."

July 7, Talk with you: "After you receive this letter you will not have to look for another, nor write another. Yes, I'm on my way home. It will be, I think, the end of July before I'll be able to talk with you, but at least I've started. I can hardly believe it."

PHILADELPHIA & SUBURBS, July 23, 1945--December 3, 1975

Dad, July 1945

Dad sailed from France, arriving in the States on July 23, 1945. On July 28, his separation papers were processed at the Indiantown Gap Military Reservation in Pennsylvania. He had served in the army for 3 years, 8 months, and 30 days.

Having met Mary Shaw McDiarmid in March, 1943, having shared only a few double dates before shipping out six-weeks later, and having weathered her initial skepticism, Dad had courted her through 150 letters written over the course of 27 months. Just one month after his return, maybe on a long, hot day in August, the love of his life rewarded his persistence and affection by accepting his proposal. (One week after that, he began working as a desk salesman at the West Philadelphia office of Joseph T. Ryerson and Sons Steel Company. He remained there until his death.

Dad wrote another 101 letters to his Shawnee in North Carolina. Other than during several weekend trips to Raleigh by train, Mother and Dad planned their wedding, as they had conducted their courtship--long-distance.

January 8, 1946, Parachute: Along with his medals, citations, jump maps, and shrapnel scars, Dad returned from the European Theater with something else, for, as he wrote, “Tomorrow I’ll take my parachute to Margaret and have her add a bit of sex appeal to it. You will look lovely in it.” The peignoir set Margaret made remains in the family

Dad resumed night classes in metallurgy and business at Drexel. His supervisor at Ryerson must have been impressed.

At the same time, he looked long and hard for a house, nearly concluding that he and Mother would have to rent; and, when he finally found a duplex in Yeadon, a short drive from Ryerson, and from his parents' row house in West Philadelphia, he stretched his budget to buy it. Then, he worked hard to prepare it for Mother and the child or two that they must have wanted. Knowing him as we do, none of that would have been easy, but we also surely know that he put his heart and soul into it.

Mother and Dad were married on April 5, 1946, in Raleigh. In July, 1947, they were blessed with twins, filling the house. However, when Mother's mother, our Mama Diarmid, exclaimed that now they had "a family," Mother replied, "It's a start."

In 1952, they purchased the larger but modest house of their dreams in Springfield, a few miles farther west. Two more children soon completed the family, and Mama Diarmid moved in to help. Throughout the rest of his life, Dad's marriage, his family, and his deep faith, were more important to him than anything else on God's earth.

In 1960, following the death of his beloved father, Dad again resumed night classes at Drexel, finally earning the degree of Bachelor of Science in 1968--the same year that our oldest sibling, Lenda, was awarded a diploma as a Registered Nurse.

Over the years, though Ryerson offered Dad several managerial promotions, he chose instead to remain at his desk and with his lower salary, always clear that he preferred more time with Mother and us, at home in Springfield near his mother and older sister, Ann Theilacker, and her family, and not far from his younger sister, Ida Erwin, and family. Rather than living to work, Dad worked to live. And, along with many other families from Dad's Fourth Presbyterian, all of us became active in the Springfield Presbyterian Church.

Sadly, after a painful, year-long battle with multiple myeloma, Dad died in 1975, at only 58. We buried him in Raeford; in 1989, we buried Mother next to him. Till the end of his life, Dad was grateful for the life and family he'd been given, a life and a love he'd fought hard to win.

Just before she died, Mother gave the house to Lenda, who, along with her husband of 54 years, has raised five sons there, and where she now welcomes her siblings, her children, her grandchildren, her neighbors, and her many friends.

That would have given Dad great joy.

DEDICATED to the memory of Catherine Shaw Montague Jenkins,

our beloved sister & keeper of memories.

AWARDS

- American Defense Service Medal

- Presidential Unit Citation

- Good Conduct Medal

- Bronze Star Medal

- Purple Heart Medal

- European African Middle Eastern Service Medal with 7 Bronze Service Stars

- Certificate of Merit Citation for Excellence as Forward Observer During Bastogne

- Three Combat Jump Stars on his Wings

- Others, from other countries

Bibliography

- Barron, Leo, and Don Cygan. No Silent Night: The Christmas Battle for Bastogne. New York: New American Library, 2012

- Breuer, William B. Operation Dragoon: The Allied Invasion of the South of France. Novato, CA: Presidio, 1987.

- Hanlon, John. "500 Sheets Weigh on a Yankeed Mind." Boston: Boston Globe, November 9, 1947.

- Willems, Filip. Fire Mission! Battery Adjust!: The History of the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery. Bastogne, Belgium: self-published, 2018.

- Yockelson, Mitchell. The Paratrooper Generals: Matthew Ridgway, Maxwell Taylor, and the American Airborne from D-Day through Normandy. Guilford, Connecticut: Stackpole Books, 2020.

Acknowledgements:

Many thanks to those who have helped us.

-

- Amy Turner Montague: Years ago, Amy read the letters, stored each one in its own archival folder, and created a meticulous data-base for them.

- Filip D. Willems, for his website, The 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Website, and his book, #4 in the Bibliography.

- Mary and Thom Spagnol, Anthony Spagnol's children.